Afrin Under Siege: Turkey Enters the Syrian War

https://flic.kr/p/22EJaQG

https://flic.kr/p/22EJaQG

The Syrian Civil War has seen multiple evolutions since its origins in March 2011 with anti-government protests against the dictatorship of Bashar Al-Assad. With ISIS nearly defeated militarily, the war now appears to be undergoing another of these evolutions. Pro-Assad forces, including loyal Syrian remnants, Russian Forces, Hezbollah, and the Iranian Revolutionary Guard, have forced the rebels out of many of their strongholds amid massive human suffering, while Israel launches airstrikes against Hezbollah and Syrian targets and exchanges direct blows with Iran. In northern Syria, Western-backed Kurds and Arab anti-Assad rebels have secured much of ISIS’s formerly held territory but now find themselves in conflict with the Turkish military and their own Arab allies. This marks a dangerous new front, as regional actors enter Syria in pursuit of their own agendas on top of pre-existing social divisions and international presence, borders are blurred, and new portions of the country get submerged, or re-submerged, into war.

The new northern front, in particular, encapsulates the complexity of the conflict and the direction this latest evolution may take. Front and centre to this are Syria’s Kurds. The Kurds, frequently known as “the largest nation without a state”, find themselves split across Greater Kurdistan, a region divided between Iraq, Turkey, Iran, and Syria. In Iraq, they are engaged in their own national struggle hastened by the war against ISIS; in Turkey, they have a long history of insurgency and in Iran, an independent Kurdish state once briefly existed. Syria’s Kurds were first internationally renowned for their defence of the town of Kobane against ISIS in 2014/15. They have long held little attachment to the Syrian government, and since the conflict’s onset, have used the power vacuum to experiment with their own self-governance and democracy. Renowned for their martial skills, and fondly looked upon in the west for their treatment of women – who serve militarily alongside men – they have proven to be one of the West’s most valuable allies. In 2015, Syrian Kurds joined with like-minded local Arab partners to form the Syrian Democratic Forces. Together, with the support of Western air power, training, logistical support, and special forces, these forces now serve as the West’s go-to allies in Syria and were vital in capturing ISIS’s self-proclaimed capital Raqqa in March 2017. Thus, at present, Syria’s Kurds and their Arab allies find themselves with something unimaginable before the war – control over large portions of Syria, including all Kurdish majority areas and much of the 900km-long Turkish-Syrian border.

These successes have not come without consequences, one of which is the deep concern of neighbouring Turkey, who has its own complicated relationship with its Kurds. Turkey, a key Western ally and member of NATO, views the YPG – the armed branch of Syria’s Kurds – and those affiliated with them as terrorists, claiming that they are inseparable from Turkey’s own Kurdish militant group, the PKK, recognized by both Turkey and the West as a terrorist organization. There is a degree of historical legitimacy to such concerns – during Turkey’s own civil war with its Kurds, the PKK had a Syrian branch. Additionally, Turkish Kurds fought against ISIS in Kobane, and ideological ties, in part based on their shared socialism, exist between members of the groups. Heightening this, Turkey at present is again in conflict with the PKK, and there is worry that Kurdish success in Syria could inspire Turkish Kurds to action. Thus, as the Kurds of northern Syria consolidate power, Turkish objection, both to Kurdish control of the Syrian-Turkish border and to their Western support, has only fomented as Turkish-Western relations worsen.

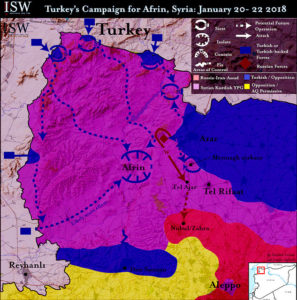

These concerns burst out on January 20th, 2018, when Turkey carried out airstrikes against the YPG in the Afrin region, located in Syria’s northwestern corner wedged against Turkey. Although airstrikes had occurred periodically before, this time was different. Soon after this round, Turkey – backed by its Syrian rebel allies, the Free Syrian Army – launched a full-fledged ground offensive into the region, prompting thousands to flee. Despite the initial shock value and Turkish claims of heavy Kurdish losses, the offensive has not yet managed to plunge deep into the region. The YPG have inflicted their own casualties on the Turkish army, and Turkey has not extended its offensive to the nearby Kurdish-controlled Manbij region amid threats from a top US general that American troops would “respond aggressively” to any Turkish backed attack. Despite these setbacks, a month after the initial assault, Turkish troops have begun to make more advances. In response to this, Pro-Syrian government troops, who have previously avoided conflict with the Kurds, have entered Afrin to “support the locals against the aggression waged by the Turkish regime” amid calls from Kurdish officials for the government to “carry out its sovereign obligations“.

All of this has left Afrin’s civilian population trapped in the middle. The region is home to 323,000 people, approximately 125,000 of whom have already been displaced, and all of whom now find themselves subject to a protracted offensive. Afrin had previously been relatively unscathed by the broader conflict, yet now its civilian population finds itself targeted by the Turkish military amid alleged indiscriminate shelling. Such actions, alleged by Human Rights Watch, would be a violation of the laws of war as Turkey is obligated to take all measures possible to reduce civilian causalities, and not attack targets with no military value. As the Turkish army makes slow gains in its occupation, pro-Assad troops enter the region in their makeshift alliance with the Kurds, and the YPG vows to protect Afrin. However, there are fears that Afrin could come to mirror Eastern Ghoutta, where a prolonged and indiscriminate siege has seen unimaginable human suffering and causalities. Despite the recent UN-backed ceasefire in Syria – prompted in part by the Ghoutta siege – Turkey has claimed its actions are not subject to the resolution as it is “not a party to the conflict” and is merely “exercising its right to self-defence based on Article 51 of the UN Charter“.

This new war between Syria’s Kurds and Turkey is one front among many in a complicated war; however, it is a telling one. The YPG, allied with anti-government Arab allies, now finds itself working with Assad, and against other anti-Kurdish Arab fighters who once cooperated in the fight against ISIS. Simultaneously, America finds itself watching as Turkey, their NATO ally, and the Kurds, their closest partners on the ground, come to blows while Russia stands back as another regional power attempts to occupy part of its Syrian ally’s territory. Additionally, as Turkey extends its fight against its own Kurds across the Syrian-Turkish border, and rocket fire has been returned into Turkey, the insularity of the conflict to Syria is called into question. Throughout this, the international community remains divided, not helped by Russia and America each having separate stakes in the conflict. When ceasefire resolutions or requests to allow humanitarian supplies into besieged areas do come from the UN, they are frequently ignored.

As the Syrian conflict nears its 7th anniversary, there is little to no end in sight. As one chapter ends, another begins, and the lines between local, regional, and international dimensions continue to blur out as the complex web of alliances shifts. After brutal sieges, bombardment, and urban warfare, cities such as Aleppo, Syria’s former business capital, and Raqqa, once the centre of ISIS’s self-proclaimed caliphate, lie in ruins and are shells of what they were before the war. As the war evolves and spreads to new fronts, the risk of this fate falling upon new regions, full of those who have already been displaced, increases. Thereby civilians, be they Kurd, Arab or other, remain trapped in an escalating conflict where they find themselves frequently targeted. With ISIS nearly defeated, those who held back from fighting one another due to a shared foe, such as Turkey with the Kurds, are no longer showing such restraint. Thus, even more layers are added to a conflict which has killed hundreds of thousands and displaced millions more.

John is a third-year political science student studying comparative politics and international relations