America’s Retreat: Russian and Chinese Leadership in the Middle East (Part II)

President Putin and President Jinping holding Russian-Chinese talks (2015)

President Putin and President Jinping holding Russian-Chinese talks (2015)

Editor’s Note: This article is the second of a two-part series on the Middle East and North Africa’s (MENA) shifting power dynamics. In Part I, Chanko explores the reasons behind the United States’ waning influence in the region.

CHINA

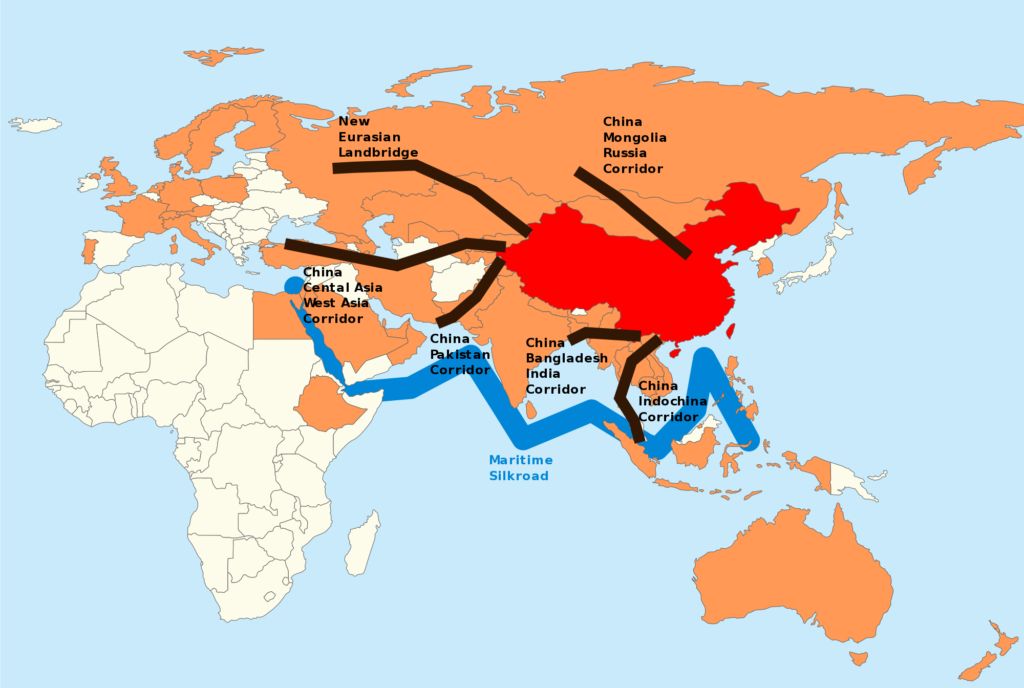

In 2014, Jinping launched the crown jewel of his foreign policy strategy: a $40 billion development investment in the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). This is China’s plan to improve infrastructure, trade, and cooperation between Eurasian countries, Oceanic countries, and the Middle East. To facilitate this epic project estimated to cost between $4-8 trillion over an indefinite timescale, China established the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB). The AIIB is a multilateral development bank launched in 2014 with $100 billion (two-thirds the capital of the Asian Development Bank and nearly half of the World Bank’s). Under the Obama administration, the U.S. declined to join the AIIB and has thus far sat out of BRI initiatives in an attempt to rebuff China’s international prestige. This move may prove costly as countries continue to get on board. To counter this effort, the US attempted to launch the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) agreement, which failed to gain popularity domestically and was put to an end following the election of President Trump.

As Obama tried to avert complete failure of U.S. intervention in the Middle East, he urged the U.S. to turn its attention back to the Far East, in a policy known as the “Pacific pivot.” Initiatives like the TPP, improving relationships with Oceanic nations, and courting Malaysia and Vietnam were seen as essential for the U.S. to get out ahead of China in terms of regional leadership. In response to American pressure in the Pacific, Jinping elected for an opportunistic strategy of “Marching West.” Through this march, China hopes to present itself as an appealing alternative to reliance on American support.

China is highly reliant on crude oil and natural gas from member states of the Gulf Cooperation Council and is the largest exporter to MENA states. In its first “Arab Policy Paper” released in 2016, China outlined its hopes to “promote China-Arab relations to a new and higher level.” This includes bilateral trade cooperation, establishing joint development projects, and exchanging military technology. Since 2016, China supplied Saudi Arabia with unmanned drones for surveillance and some with missile-firing capabilities and participated in joint anti-terrorism drills. It also sells armed and unarmed drones to Iraq, Egypt, and the UAE, something the U.S. has refrained from doing under pressure from Israel. Furthermore, China signed an agreement to help Saudi Arabia build drones for civilian and military purposes, to be sold to countries in the region, the only such Chinese drone-manufacturing cooperative in the Middle East. China has even offered to mediate diplomatic relations between longtime rivals Iran and Saudi Arabia, as it hopes to breed peace through economic development and joint commitments.

RUSSIA

For its part, Russia has moved forward by exercising its military might through interventions in Ukraine and Syria. Putin has put his military infrastructure to use by selling arms to Saudi Arabia and other countries in the Middle East. His paranoia over the 2011 American intervention in Libya and the role of the U.S. in the removal of his close ally President Yanukovych in Ukraine pushed Putin to counter American global leadership. Most recently, he struck out at the U.S. by using cyberwarfare to disrupt the 2016 presidential elections and drive a wedge into the politically polarized public sphere. Putin also authorized the annexation of Crimea, and the 2015 military intervention in Syria—the first military deployment outside former Soviet Union borders since the 1979 invasion of Afghanistan. Despite Obama’s remarks that Russia’s efforts in Syria would fail, they, in fact, turned the tide in the civil war and secured President Assad’s victory over the U.S. backed rebels. Russia’s remarkably influential intervention has set Russia up to play a bigger role in the burgeoning conflict in the Middle East.

In Putin’s address at the 70th UN General Assembly, he outlined how U.S. intervention in the Middle East was an utter failure, breached state sovereignty, and only deepened conflicts. Putin also stated that the West was making “an enormous mistake to refuse to cooperate with the Syrian government and its armed forces, who are valiantly fighting terrorism face to face.” From the Kremlin’s vantage point, the U.S. helped produce failed states in Libya and Yemen, and allowed instability and religious extremism to flourish in MENA.

Russia has a strong influence in the region since the USSR educated, trained, and supported multiple local independence movements. Its historical ties have helped to develop relationships with state governments. For example, the President of the Palestinian National Authority Mahmoud Abbas earned a doctorate at the Peoples’ Friendship University in Moscow. Putin has officially stated that he supports a two-state solution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. With Russian diplomat Mikhail Bogdanov spearheading diplomacy as special envoy to Syria, Abbas has helped Putin win favour with Egypt’s new ruler Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, as they establish open communication and security talks. In addition, Russia has been supporting Field Marshal Khalifa Haftar’s bid for power as the leader of the Libyan National Army. If Haftar were to establish himself as dictator of Libya, Russia would have close allies in Libya and Egypt to buttress against future Western-supported opposition.

COMPLEMENTARITY

The strategic partnership between Russia and China is based on complementary goals and capabilities. While Russia brings tested military experience and a history of close relations with states in the Middle East, China brings a titanic economy and burgeoning economic development prospects. Together, they may soon offer a counterbalancing force to U.S. regional supremacy and provide Middle Eastern countries with support in conflicts. Both Russia and China remained neutral in the UN-sanctioned intervention in Libya, despite their heavy investment in the state. They abstained from the resolution that provided NATO forces with the ability to defend innocent civilians from slaughter by Gaddafi’s forces. However, the U.S. stretched the limits of the resolution and actively bombed Gaddafi’s strongholds, leading to his capture and public execution. Since then, Putin and Jinping refuse to sacrifice their investments in other states, no matter the human costs.

The rise of global terrorism in recent years provides an incentive for these two countries to intervene and provide military support, as they both face domestic terrorist issues. Russia has faced difficulties in the North Caucuses region with two wars fought against its federal subject, Chechnya. With the rise of ISIL, more than 2,500 Russian sympathizers (the most of any foreign country) have joined its ranks. The Kremlin fears that these terrorists will find their way back into Russia as ISIL crumbles and cause trouble domestically.

Similarly, China has 11 million Uyghurs, ethnically distinct South Asians whose majority practices Islam and have only been under Chinese rule since 1949. Conflicts have arisen as China discriminates against the Uyghur population. A number of terrorists from Xinjiang have gone to fight for the Houthis in the bloody Yemeni civil war. Jinping fears “three evil forces:” terrorism, religious extremism, and separatism, and hopes to quell terrorist conflict in Yemen to cut off any possibility of resistance from its own Muslim population. China has started to build its first ever overseas naval base on the eastern tip of Djibouti, close to Yemen. Though it has been presented as an anti-piracy effort in the Gulf of Aden, it will likely be used for deployments of Chinese peacekeeping troops in Africa and missions in the Gulf.

A striking rise in repressive state action has caused problems for the United States and its allies. In the Constructivist view, the foundational aspects of international relations are historically and socially constructed. Constructivists would say that the internal nature of states and ideological differences would provide an explanation for state action. The U.S. and its western allies cannot accept human rights scandals in repressive state regimes because of their deep belief in individual rights over the sovereignty of the state. They have denounced such actions, such as Israel’s continuing development of settlements in disputed territory and President Erdogan’s elimination of political rivals and suppression of protests. Erdogan acknowledged that his relationship with Obama was “disappointing,” and urged Turkish politicians to reevaluate EU membership and consider the SCO as an alternative. Neither China nor Russia have issues with these actions and can invite Turkey and Israel to friendship with open arms. It is likely that states like Egypt and Israel, that have up until recently had close ties to the United States, will play the U.S. and Russia against each other. In this way, if their leaders push the U.S. and Russia to compete for their friendship, Egypt and Israel can extract better deals and benefits.

AMERICA’S INCOHERENT GRAND STRATEGY

The pragmatic and unrestricted approach with which Russia and China have tackled international relations issues’ in the Middle East gives them an advantage over the United States. While both countries can alternate strategies and move forward quickly, the U.S. is bogged down by the Hamiltonian conflicts of power in its system: The Congress and Presidency share power and often disagree over foreign policy approaches. Congress must also ratify every treaty negotiated by the executive branch. The open political field in the U.S. makes it easy for minority interest groups to mobilize and block American foreign policy developed by executives in the White House. Administrations have to work with one hand tied behind their back as they attempt to develop multilateral approaches to international conflicts. During the Cold War, in contrast, there was a perilous threat to the very foundation of America’s political freedom and very way of life. Dissenting opinions to American foreign policy were hushed and pushed to the wayside in favour of a more unified front against the Soviet Union. Thus, paradoxically, since the end of the Cold War, U.S. foreign policy strategy has been less coherent and effective, despite being the most powerful player in the entire system.

Edited by Alec Regino