At it Again: Russia-Ukraine Natural Gas Disputes

Photo Credit: Flickr User khrawlings. Accessed at: http://tinyurl.com/ohsw8ct

Photo Credit: Flickr User khrawlings. Accessed at: http://tinyurl.com/ohsw8ct

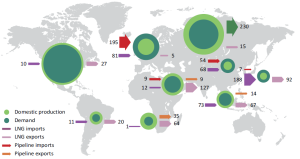

Global energy consumption is changing. Natural gas has grown to 21% of the global total primary energy supply, which is beneficial for the environment compared to emissions of other fossil fuels. Gas provides flexibility for electricity markets as it is relatively easy and quick to increase or decrease levels of generation. Like all non-renewable resources, gas reserves only occur in certain areas. This means that gas must be transported from exporting to importing countries. While natural gas markets have become more integrated, major consumers continue to rely on imports supplied through long pipelines, although technology advances are now enabling exports of liquefied forms.

Why is global energy demand changing? Growth of non-members of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) has led to increased global demand for energy, increasing production levels and competition. In addition, supply side shocks such as outages, cold weather, political disputes or economic crisis also affect global energy consumption patterns. Dependence on specific regions for natural gas makes supply extremely vulnerable to shocks. Shocks to energy supply can take many forms, and also affect the factors affecting global energy demand.

The following countries are the top natural gas exporting nations as of 2013 (volumes measured in cubic metres):

| Russia | 196,000,000,000 |

| Qatar | 113,700,000,000 |

| Norway | 107,300,000,000 |

| European Union | 93,750,000,000 |

| Canada | 88,290,000,000 |

| Netherlands | 63,420,000,000 |

| Algeria | 52,020,000,000 |

| United States | 45,840,000,000 |

| Slovakia | 45,430,000,000 |

| Bolivia | 44,940,000,000 |

Investment is increasing in facilities in the US to export liquefied petroleum gas (LPG) and liquefied natural gas (LNG), as well as in processing natural gas liquids (NGLs). These products of gas wells are versatile fuels as well as valuable raw materials for petrochemicals. These billion dollar investments exemplify a switch in America’s energy industry. Oil and gas production have boomed due to hydraulic fracturing (fracking) and horizontal drilling of shale rock, and American refineries, though somewhat inefficient, export products that compete against more competitive European refiners.

The European Union is extremely dependent on gas imports, making economies such as Germany, Italy and the UK extremely vulnerable to supply side disruptions. Following unrest between Russia and Ukraine, the UK front-month gas prices rose by 3.8%. While disputes between Russia and Ukraine have been ongoing, in mid-January 2015, Putin ordered Gazprom, the world’s biggest natural gas supplier, to cut supplies entering Ukraine, following accusations that Ukraine had been siphoning off Russian gas. Three large pipelines bringing Russian gas to Europe go through Ukraine. Consequently, following a 60% cut in gas exports to Europe by Gazprom, Bulgaria, Greece, Macedonia, Romania, Croatia and Turkey reported a complete halt in gas shipments from Russia.

Key gas importing nations according to the latest data (volumes measured in cubic metres):

| European Union | 420,600,000,000 |

| Japan | 122,200,000,000 |

| United States | 88,770,000,000 |

| Germany | 87,960,000,000 |

| Italy | 67,800,000,000 |

| China | 53,000,000,000 |

| Slovakia | 50,180,000,000 |

| United Kingdom | 48,260,000,000 |

| France | 47,710,000,000 |

| South Korea | 47,340,000,000 |

In late February 2015 disputes over Russia withholding supplies to Ukraine and Ukraine’s Naftogaz having unpaid bills for prepaid contracts were still not resolved. Establishing prepayments was a solution to previous gas disputes regarding late payments by Ukraine in late 2014, following a shut off of gas from Russia to Ukraine in June 2014. However, the disputes are ongoing and the agreement seems to have been ineffective. These repetitive disputes risk complete cut offs of Russian gas supplies through Ukraine, severely threatening European gas supply. If Gazprom shuts down gas pipelines through Ukraine, 55% of the Russian natural gas bound for Europe will be cut from the market. Pricing disputes disrupted Russian flows to Europe amid freezing weather in 2006 and 2009. Since then, Gazprom has built a pipeline under the Baltic Sea to Germany to bypass Ukraine, reducing the risk of cuts for European consumers.

Gazprom now intends to diversify its export routes, to deliver stable supplies to the EU market by mitigating political risks within Ukraine. The most recent project is a gas pipeline through Turkey to the Greek border, with the capacity to transport 63 billion cubic meters via pipe laid under the Black Sea. This pipeline is approximately half of what the company’s three Ukraine pipelines deliver. The pipeline would be an alternative export route to flow through Ukraine, along with Nord Stream, Blue Stream and the Yamal Europe gas pipelines. However, Ukraine is a logical transit country given its location in Europe and specified places of delivery in Gazprom’s current long-term contracts with EU customers, which have not been outlined with the proposed pipeline.

Europe’s vulnerability to supply shocks resulting from tensions between Russia and Ukraine exemplify how integrated and interdependent international energy markets have become. While markets can absorb some shocks, the EU is currently planning to develop an energy union, which would reduce dependence on Russia while also facilitating a transition to a low-carbon economy. While the most obvious solution would be to address the crisis in Ukraine, there are less politically challenging alternatives to ensure Europe’s gas supply. Improving energy security through national and regional strategies specific to natural gas is a more implementable option.

Shocks in international energy markets often prompt widespread hysteria regarding physical shortages and ideas of “energy security measures” reminiscent of the oil crisis of 1973. However, technology improvements and appropriate price and extraction rates limit the possibility of physical shortages occurring. A physical shortage of primary energy products is extremely unlikely as market forces ensure that, in a situation of shortage, there will be supply of a good albeit at a high price. To avoid inhibitive high prices of energy products following a supply shock, concrete steps can be taken to improve energy security. These measures do not require the extreme response of the US to the 1973 oil crisis, where exports of crude oil have been banned since 1975.

European gas importers need to assess their vulnerabilities and response options for potential disruptions in natural gas supply. A modern approach to energy security could include policies on import reduction, improved energy efficiency, import source diversification, research and development, and investment in alternative energy technologies. Previously, diversification of import sources was infeasible, but with the above mentioned American liquefied gas investment it may be possible to diversify import sources and entry points by importing from the US. Other measures include increasing resilience through improved storage in underground reservoirs and pipelines by increasing production capacity and holding more reserve stocks of gas. Granted, there are geological and technical barriers to storage, as well as the problem that gas transport is difficult to scale up. But that is why utilising a range of policy measures will secure Europe’s natural gas supply and make them less dependent on unreliable exports from Russia through Ukraine.

Feature image obtained from: Flickr User khrawlings. Accessed at: http://tinyurl.com/ohsw8ct