Austria’s Integration Problem

VIENNA, AUSTRIA - JULY 05: Austrian Chancellor Sebastian Kurz, German Interior Minister Horst Seehofer (not pictured) and Austrian Vice-Chancellor Heinz-Christian Strache (not pictured) speak to the media after their meeting at the Federal Chancellery on July 5, 2018 in Vienna, Austria. Seehoher is in Vienna to discuss the implementation of his plans for new immigration measures on the German-Austrian border that will require the cooperation of Austrian authorities. (Photo by Michael Gruber/Getty Images)

VIENNA, AUSTRIA - JULY 05: Austrian Chancellor Sebastian Kurz, German Interior Minister Horst Seehofer (not pictured) and Austrian Vice-Chancellor Heinz-Christian Strache (not pictured) speak to the media after their meeting at the Federal Chancellery on July 5, 2018 in Vienna, Austria. Seehoher is in Vienna to discuss the implementation of his plans for new immigration measures on the German-Austrian border that will require the cooperation of Austrian authorities. (Photo by Michael Gruber/Getty Images)

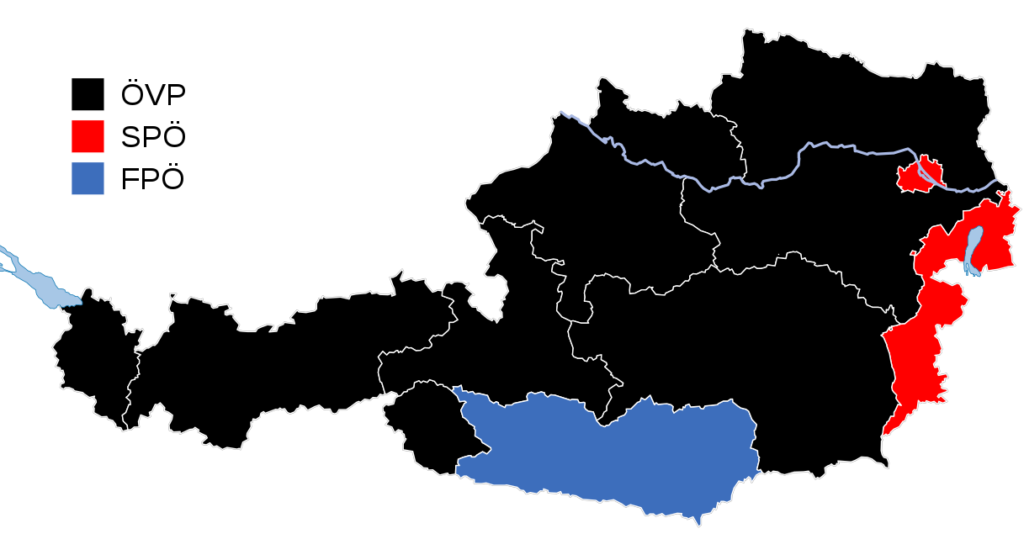

After Chancellor Sebastian Kurz won the Austrian elections in December 2017 and formed the coalition between the center-right People’s Party (OVP) and the far-right Freedom Party (FPO), the country began a crackdown on so called “political Islam” that entails deporting imams, shutting down mosques, and a hardline approach on migrants. Really, this is anti-immigrant and anti-muslim policy under the veil of security from extremism. Already its effects of aggravated social tension and exclusion are taking hold. In the context of Europe’s far-right political climate and the U.S.’s recent immigration system changes, Kurz’s government is getting away with it.

On June 8th, the 31-year old Chancellor ordered the closure of seven mosques and the expulsion of 60 imams and their families that had apparent ties to the Turkish-Islamic Cultural Associations (ATIB) organization, a branch of Turkey’s religious affairs agency. The Arab Religious Association, the organization running the mosques, has also been ordered to shut down. One of the mosques was closed under the impression that it had ties with Grey Wolves, the far-right Turkish nationalist group. Saying that “parallel societies, political Islam and radicalization have no place in [Austria]”, Kurz assured that the steps taken were intended to target and eliminate extremism, not Islam as a whole.

For Austrian muslims and immigrants, this is hard to believe after the OVP’s election campaign, which hinted heavily at anti-immigrant populism. They promised to halt illegal immigration altogether, by sending refugees and asylum seekers to rescue and protection centres outside of Europe. The integration of Muslims into the country has become an issue of protecting European identity and preserving mainstream culture, which is something the OVP used to pave the way to electoral success. The problem is that allusions to Islamophobia are now mainstream. A survey from 2017 found that 65% of Austrians agreed that further immigration from mainly Muslim countries should be stopped. During their incumbency, the OVP-FPO coalition has kept this rhetoric alive by decreasing social welfare for people with limited or no German language skills, reducing funding for integration measures, and planning a headscarf ban for elementary school children. The FPO’s election manifesto actually called for the outright rejection of immigration, and blatantly stated how the party doesn’t see Islam as a part of Austria.

In the past, there would have been significant outcry against the Austrian government’s restrictive policies. This is amplified by the fact that they’re being enacted by the Freedom Party, whose founding members were former members of the Nazi party, and who are known for their radical, racist, and sexist remarks. Although 20,000 protestors of mainly students and leftist groups gathered against the new government in January, it was underwhelming compared to the protests in February 2000, the last time the FPO was elected, during which there were over 150,000 demonstrators. After the 2015 refugee crisis, views have clearly shifted.

This lack of challenge to the government notably applies outside Austria’s borders as well. As the FPO came into power in 2000, concerned EU members ordered sanctions against the Austrian government, halting diplomatic ties and preventing Austrian candidates from joining international organizations. This was purely on the basis of EU values; “liberty, democracy, respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms”, which they feared would become strained under the FPO. Now, member states like Germany, Hungary, and Italy are teaming up with Austria to enact stricter protection of Europe’s external border.

Turkey’s President Tayyip Erdogan is among the few that have denounced Austria, warning that Kurz is “leading the world toward a war between the cross and the crescent”. Though his vision of a clash of civilizations is unlikely, ideological and religious differences of the two governments have certainly emphasized long-existing knots in their relationship. Austria’s Muslim population of approximately 600,000 shares the views of their Turkish counterparts, as Kurz’s policies are effectively “discrediting the religious community”, and “weakening [its] structures”.

By shutting down Islamic associations and removing their religious leaders to avoid “radicalism”, Kurz’s government is magnifying nationalist views while their paternalism shapes Austrian Muslims’ identity, placing limits on their expression that adherents of other religions have no trouble with. The reproaching of the mosques was sparked by photos of children who had dressed up and played dead to re-enact a World War I battle (which ATIB itself condemned afterwards), rather than any actual implicit or explicit sign of terrorism.

The Austrian government’s political-Islam action also draws on the 2015 law on Islam that Kurz, Integration Minister at the time, was largely involved in. Among other things, it prohibits foreign funding for Islamic associations, and obliges Muslims to have a “positive attitude towards the state and society”. The former has not been an issue in the myriad other nations such as Cuba or the Philippines where Turkey is funding mosques, and the latter has traces of authoritarianism, insinuating that whatever the Austrian state or society does, Muslims should agree with. It’s almost foreshadowing a situation of heightened social intolerance and a harsher law on Islam being enforced. The Muslim-Austrian identity is belittled with this legislation. Where is the law on Christianity? The law on Judaism? Is a law on really Islam necessary if the same basic civic guidelines are already outlined in the country’s constitution?

Now as Austria has already singled out followers of Islam and labelled them as members of a “parallel society” that need to be merged with mainstream European norms and culture, it’s not only a question of religious liberty but also of social isolation. Through Kurz’s discourse, Muslim migrants in Austria have become the “other”; the radicals, the extremists, the terrorists. Austrians start to regard them with sentiments of suspicion and fear, which is exactly what Kurz’s coalition then extracts to gain support for hardline migrant policies. The Austrian government does not have an integration problem on their hands. Rather, it has an integration strategy that’s keeping the powers that be on top of domestic politics.

Edited by Gracie Webb