Too Big To Fail: What Next For US-Pakistani Relations?

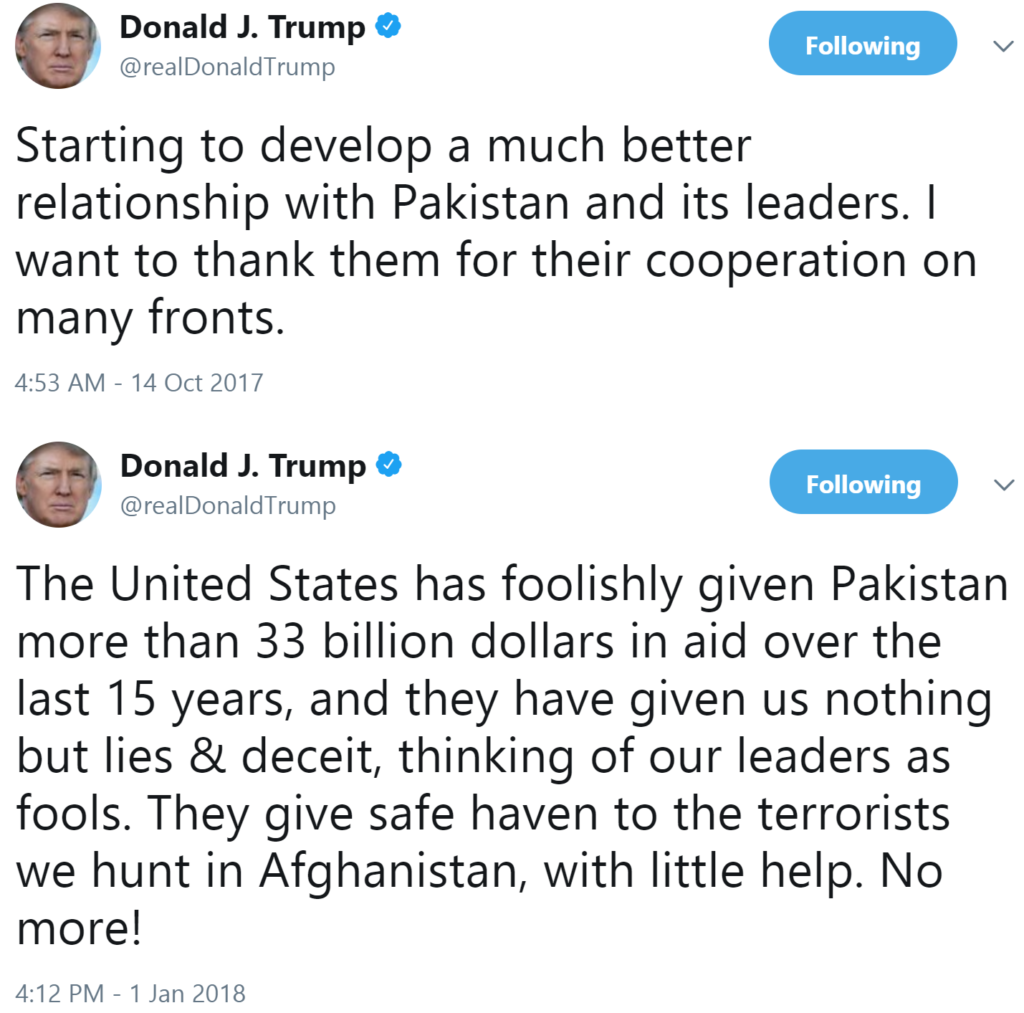

2018 started on the worst possible note for US-Pakistani relations. Donald Trump’s inaugural tweet accused Pakistan of pocketing $33 billion in US aid since 2002, providing safe haven to terrorists and even thinking US leaders are “fools” (they’re probably right). The US followed up by cutting security assistance to Pakistan. Islamabad categorically denied Trump’s accusations and summoned the US ambassador for a diplomatic démarche. While Trump’s fiercely anti-Pakistan tweets won Trump immediate brownie points in India, it does not exactly boost US diplomatic leverage in South Asia. In fact, the $255 million cut in foreign military assistance to Pakistan is, to use the words of the late General Zia when offered an aid package by the Carter White House, “peanuts”.

The recent rupture in the relationship between Islamabad and Washington can be traced back to 2011 with the unilateral assassination of Osama Bin Laden in Abbottabad, the Raymond Davis scandal and the seven-month delay in the US “statement of regret” for the accidental killing of 28 Pakistani soldiers. Pakistan is mission critical to US national security for two key reasons: One, Pakistan’s military intelligence agency’s Afghan proxies can make a US/NATO withdrawal from Afghanistan a nightmare. Two, Pakistan is a nuclear state with the most powerful armed forces in the Islamic world. An anti-American Pakistan allied to Iran, Russia or China will compromise US interests in the Gulf and the wider Arab-Islamic world.

Waging proxy war has been a part of Pakistan’s military doctrine since the 1948 Kashmir War. If US-allied Pakistan has waged proxy wars in India and Afghanistan since the late 1980s, imagine the scale of violence its spies and generals could export outside its border without the restraint of US military and economic aid. Not even President Obama’s extensive use of drone strikes and Delta Force hit squads have deterred the ISI and caused it to jettison clients like the Haqqani network or sectarian jihadists at home, in Kashmir and in Afghanistan. Trump’s boastful tweets mean squat to the world’s only major state run by spies from an all-powerful military intelligence agency that can and does depose Prime Ministers at will.

Even though Pakistan’s generals were humiliated by President Obama’s Navy SEAL raid on Osama Bin Laden’s compound in the garrison city of Abbottabad (a stone throw from Kakul, the Pakistan Army’s West Point), they did not break their economic umbilical cord with the Pentagon, forged in the 1950s at the height of the Cold War. Pakistan played a critical role in President Nixon’s secret opening to China in 1971, President Reagan’s anti-Soviet jihad in Afghanistan, and President Bush Jr.’s ‘War on Terror’. The military dictatorships of Ayyub Khan (1958-69), Zia ul-Haq (1977-88) and Pervez Musharraf (1999-2007) were all staunchly supported by Washington, irrespective of their policies in Kashmir, India and Afghanistan, let alone violations of human rights or Constitutional chicanery at home. As President Franklin D. Roosevelt once reportedly remarked about Nicaragua’s Somoza Sr: “He may be an S.O.B, but he’s our S.O.B.”

The Dangers of Non-State Nuclear Proliferation

The nightmare scenario for Pakistan, the US, India, and the world is a possible acquisition of nuclear weapons by local foreign Islamic terrorists. This is not implausible. Historically, Pakistani military intelligence has also sold black market nuclear components or centrifuges to Iran, Libya, North Korea and even Saudi Arabia. This is what makes the ISI’s threats of retaliation to any wholesale aid cutoff so credible to the Pentagon, the CIA and the NCC policy planners. The Afghan Taliban have historically found weapons, logistic support, financing and political support from the Pashtun generals of the ISI, notably the late General Hamid Gul and General Asad Durrani, both apologists for Islamist terrorism on Western media.

A nuclear “rogue state” run by jihadi terrorists is Washington’s ultimate worst case scenario. In 2013, a summary of the U.S intelligence community’s “black budget” report showed that the U.S had ramped up its surveillance of Pakistan’s nuclear program, showcasing Washington’s distrust of Pakistan’s intentions, or even competence, in keeping nuclear weapons away from the hands of terrorist organizations. Harvard University’s “Securing the Bomb 2010” study concluded that Pakistan’s nuclear stockpile “faces a greater threat from Islamic terror groups seeking nuclear weapons than any other nuclear stockpile on earth.” The study cited widespread corruption and elements of jihadist sympathizers in the government and military as potential avenues for non-state nuclear proliferation. Former CIA director George Tenet even reported that, shortly before the 9/11 attacks, Al-Qaeda ringleaders Osama Bin Laden and Ayman al-Zawahiri met with Pakistani nuclear officials to recieve rough instructions for an improvised nuclear device. Thankfully, Al-Qaeda looks to have failed in its attempt at nuclear arms development. Coupled with signs of improved Pakistani nuclear security from a 2016 study by the Congressional Research Service, the chances of a nuclear-armed terrorist group look slim.

The Afghan Quagmire

Afghanistan has been the longest quagmire in American military history – 17 years after the October 2001 invasion by President George W. Bush, there is no immediate prospect of decisive military victory over the Taliban. Pakistan will continue to undermine the US-allied, US-installed Afghan government in Kabul, whose Tajik/Uzbek intelligence security elite are enemies of the Pakistani-backed Taliban and thus pro-India, not pro-Pakistan. Islamabad’s Afghan policy is a derivative of its existential conflict with its arch-rival India; with greater bilateral relations developing between New Dehli and Kabul, both nations look to systematically contain Pakistani expansionism into Kashmir and the Durand Line as well as denounce Islamabad as a “mothership” of terrorism infront of the international community.

As Donald Trump tightens sanctions on Iran and attempts to end Obama’s nuclear deal with the Ayatollah’s regime, the US needs its air and land coordinators and CIA black sites in Pakistan. The US has also been unable to find alternative supply routes into Afghanistan. India has invested in Iran’s Gulf port Chabahar but the current hostility to the Khamenei regime in Washington makes it politically impossible for the Trump Administration to engage Indian contractors to provide an overland logistical bridge from Chabahar to Afghanistan.

The State Department’s suspension of $900 million in Coalition Support Fund (CSF) should ideally trigger a policy rethink in the Pakistan Army’s Rawalpindi GHQ. The US decision to suspend CSF will have an impact on the Pakistani Air Forces military hardware budget and thus on the balance of aerial power projection in South Asia. If Trump punishes Pakistan by withholding IMF bankrolls or imposing sanctions, he could easily trigger a financial collapse. This could precipitate the very jihadist takeover of Pakistan’s military and nuclear assets Washington fears most.

Pakistan’s pivot to China and Russia

However, Pakistan’s key ally and geopolitical partner is now China, not the United States. China has pledged to invest $62 billion into the Pakistani economy via the Chinese Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), the flagship template for its One Belt, One Road program. Pakistan is now more than just a geopolitical counterweight to India for the Politburo. China’s pivot to Pakistan is a geo-economic game-changer for the South-Asian ‘black sheep’, as CPEC can potentially turn Pakistan into a transnational economic hub. Moreover, the Pakistani military’s proficiency in proxy warfare and effective counter-terrorism campaigns (when they feel like it) will prove useful against the emerging security threats from ethnic Ugyhur secessionists and radical jihadists in its Xinjiang province – Beijing’s Western link to the rest of Asia.

As the world’s largest natural gas producer, Russia is a natural energy partner for Pakistan. In 2014, Moscow lifted its decades’ old arms embargo against Pakistan and has sold Russian Mi-35 Hind attack helicopters as well as conducted regular joint military exercises. The Kremlin even hosted delegations of the Afghan Taliban despite enraging New Delhi and Washington. Moscow and Beijing resisted pressure from New Delhi to condemn Pakistan as a “state sponsor of terrorism” in the last BRIC summit. A new Pakistani-Chinese-Russian entente will not only have a profound impact on the geopolitics of Afghanistan and the Indian subcontinent but also on the global balance of power. It will also reduce US diplomatic and financial leverage on Pakistan, particularly in its border conflicts with the Afghan government in Kabul.

Thanks to the Obama drone campaign, public opinion in Pakistan has turned virulently anti-American, an emotion amplified by Trump’s anti-Islam rhetoric, visa ban and decision to recognize Jerusalem as the capital of Israel. It will be extremely difficult for even a pro-Western Pakistan leader to heal this wound and normalize ruptured relations. Yet, the cost of maintaining clandestine relations with the Haqqani network and the Afghan Taliban just shot up for the corps commanders who run the Pakistan Army and the Director General of the ISI. At the very least, expect suicide bomb attacks and military skirmishes in the streets of Kabul and other Afghan cities to increase as the Emirs of the Haqqani/Taliban send their own lethal messages to the world. Washington cannot afford to lose its ‘special relationship’ with Islamabad. It’s too big to fail.

Edited by Benjamin Aloi