California’s Answer to Homelessness: Not in My Backyard

"The death and life of great Californian Cities"

On December 16, 2019, The Supreme Court of the United States declined to review the landmark Boise v. Martin ruling of the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals. In doing so, SCOTUS upheld the 2018 decision to strike down city ordinances that ban homeless encampments in public spaces. While seemingly anticlimactic, the aftermath of this ‘non-decision’ immediately caused a stir among city officials under the 9th Circuit’s appellate jurisdiction.

The 9th Circuit covers the Western-most portion of the United States, including California, which is home to nearly 50 percent of all unsheltered Americans. In 2018, Boise v. Martin confirmed the right of these 89,543 Californians to sleep on sidewalks or in public parks when there is no shelter space available. By letting the Boise verdict stand, SCOTUS’s decision will bring California’s homeless demographic further into the orbit of city planning. But, the decision also means that it is “back to the drawing board” for local officials already grappling with the most severe affordable housing crisis in American history.

Golden State Crisis

In 2018, The Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) reported a nationwide spike in unsheltered homelessness, fuelled almost entirely by California. The 2018 Annual Homeless Assessment Report (AHAR) to Congress singled out encampments in Los Angeles County and the Bay Area, making them the most recent targets of President Donald Trump’s crusade to Make America Great Again. For Trump and HUD secretary, Ben Carson, California’s crisis illustrates the failure of Democratic policies that are too lenient on individuals experiencing homelessness.

Trump recently suggested using police force to “help people off the street and into shelter or housing,” and he is not the first to do so. Without an effective framework for reducing homelessness, city governments often turn to law enforcement to minimize its visibility. For decades, this logic has motivated efforts to rid city centres of encampments through police raids, relocation programs, and defensive architecture.

In a September 2019 statement to CNN, President Trump mourned the decline of “great California cities” as a consequence of growing encampments. He explained, “they moved to Los Angeles, or they moved to San Francisco because of the prestige of the city, and all of the sudden, they have tents. Hundreds and hundreds of tents.”

On homelessness, Trump said he's spoken to foreign tenants who've moved to California cities for the "prestige" but now want to leave because there are homeless people on the streets — "our best streets, our best entrances to buildings." pic.twitter.com/hhWS5Dezy9

— Daniel Dale (@ddale8) September 17, 2019

President Donald Trump to CNN on California’s Homelessness Crisis

It comes as no surprise that Trump’s words resonated with urbanites in Los Angeles and San Francisco. Historically, California cities have embodied a sense of “prestige” through their wide-open spaces, flourishing economies, and diverse populations.

In some ways, this is still the case for California. After the 2008 recession, state GDP sustained unprecedented growth thanks to an influx of information and communications technology (ICT) companies, making it the fifth-largest economy in the world. What’s more, California is a national hub of cultural diversity and progressivism, wherein state leaders describe themselves as being “fundamentally at odds” with the Trump administration. For these reasons, newcomers still flock to California, hoping to claim their share of what conservative economist and urbanist, Edward Glaeser, calls “the triumph of the city.”

California’s major cities are anything but triumphant, however. With a staggering affordable housing shortage underway, the homeless epidemic sweeping California points, above all, to poor city management. Currently, over 40 percent of California homeowners and renters are cost-burdened, meaning they spend more than 30 percent of their incomes on housing. High costs of living and stagnant wages are responsible for both the affordable housing shortage and the ongoing humanitarian crisis playing out on the streets of California cities.

Although Governor Gavin Newsom regularly promises increased spending on homelessness, local officials are torn between their most vocal constituents: homeowners and real estate developers. The contentious NIMBY-YIMBY debate is evidence of the many obstacles to affordable housing and urban development in California cities.

NIMBY, standing for “not in my backyard,” is a grassroots movement led by homeowners who view urban densification as a threat to their property investments. NIMBY has grown into a diverse movement ranging from liberal appeals for environmental protection, to more conservative campaigns aimed at preserving traditional community values. In either case, activists are hostile to the externalities of development and social change, making them natural opponents of affordable housing and expanded homeless services.

The success of NIMBY inspired an unlikely coalition between real estate developers and young progressives. YIMBY, meaning “yes in my backyard,” promotes deregulation as a way to drive down housing costs, rendering cities more accessible for low-income earners. By couching development discourse in social justice terms, YIMBY is convincing liberal Americans to overlook the profit-oriented aims of real estate developers. Like other neoliberal platforms, YIMBY is an attractive fix, promising trickle-down benefits for its supporters. While its supply-and-demand logic does apply to young urban professionals employed in ICT industries, YIMBY is not a holistic solution for a problem as protracted and varied as California’s homeless epidemic.

Despite their many flaws, both NIMBY and YIMBY offer a valuable lesson for city planning in California—the importance of community consultation. Local policymaking must involve a dialogue at the grassroots level to truly uphold community interests. It follows that the genesis of NIMBY and YIMBY came from frustrated constituents who wanted a say in the direction of their local state of affairs.

However, the language of “my backyard” limits this dialogue by implying that ownership, or rentership, is a prerequisite for input in local policymaking. Failure to broaden the discourse of urban planning beyond the backyards of homeowners and renters contributes to public policy that overlooks individuals experiencing homelessness. As a result, thousands of Californians have no choice but to sleep on the streets of Los Angeles and San Francisco every night.

Making the Case

Efforts to purge public spaces of encampments predate Trump’s war on poverty in the state of California. Boise v. Martin traces back to 2007 when a group of homeless residents from Boise, Idaho, challenged a series of city ordinances prohibiting the acts of “occupying, lodging, or sleeping” in public places. The plaintiffs included Robert Martin, who was fined $150 for resting on a public sidewalk while making his way to a local shelter. As of October 2009, the DC-based nonprofit, The National Law Centre on Homelessness and Poverty, advocated on behalf of Martin, calling the ordinances unconstitutional.

Following their initial failure at the district level, Martin’s representatives embarked on a lengthy litigation process in 2014, ultimately filing an appeal to the 9th Circuit in September 2017. Finally, in April 2018, the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals invoked the “cruel and unusual punishment” clause of the 8th Amendment to invalidate the ordinances given the lack of shelter spaces. As such, the precedent established by Boise v. Martin forces city governments to consider the rights of individuals experiencing homelessness when formulating public policy.

Along with Boise officials themselves, the ruling was most fiercely contested in California, prompting the City of Los Angeles to file an Amicus Curiae brief to the Supreme Court in September 2019. Los Angeles representatives supported Boise, fearing the ruling would curtail their authority by forcing them to “surrender their streets, sidewalks, parks, river beds, and other public spaces to vast encampments.”

Although Boise received ample support from other Western cities, The Supreme Court rejected its appeal to review the previous ruling, thereby letting it stand in the 9th Circuit. Consequently, SCOTUS affirmed the lower court’s finding that “just as the state may not criminalize the state of being ‘homeless in public places,’ the state may not ‘criminalize conduct that is an unavoidable consequence of being homeless – namely sitting, lying, or sleeping on the streets.’”

Despite aggressive pushback from city officials, SCOTUS’s decision, like the Boise ruling itself, was lauded by homeless advocacy groups as a momentous human rights victory, with revolutionary implications for urban poverty in California. At the time of writing, it is too soon to say how city planning will change under these new parameters, or if it will change at all. But, the value of Boise v. Martin lies far beyond its policy implications. By forcing cities to recognize the 8th Amendment rights of unsheltered Americans, The Supreme Court shifted the focus of the homeless debate from the individual to the systemic level.

Trump is not alone in blaming homeless people for the death of “great California cities.” Indeed, scapegoating is a tempting response for a situation as dire and complex as this one. However, his claims of “lost prestige” are hollow references to a golden age that never was. Cities like Los Angeles are not victims of encampments. Rather, Los Angeles residents are the victims of myopic city planning that prioritizes the backyards of the few at the expense of the many.

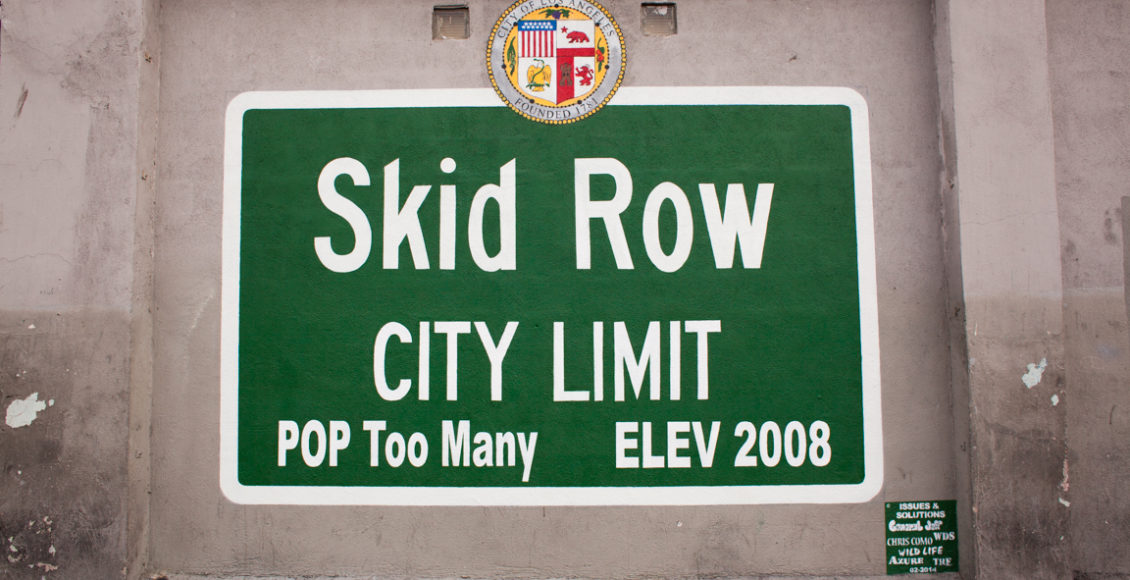

Featured Image “Skid Row Super Mural” by Stephen Zeigler is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

Edited by Christopher Ciafro