Central America’s Second Coming of the Anti-Establishment

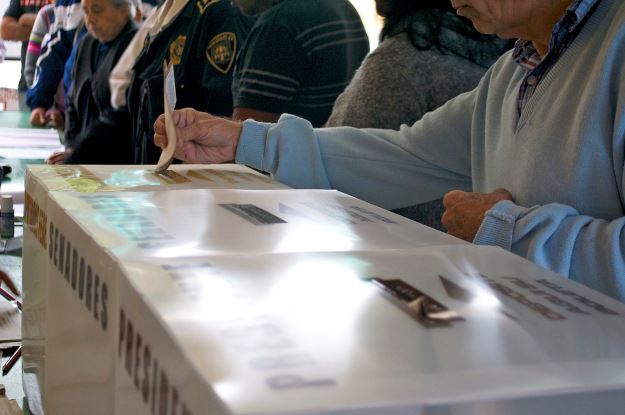

There is unrest in Honduras. As the electoral commission declared the incumbent Juan Orlando Hernandez as President of Honduras, people have taken to the streets with indignity decrying electoral fraud. The results are also contested by the opposition presidential candidate Salvador Nasralla. A former sportscaster, Nasralla asked for the results to be annulled, but with support from Washington, this seems dismal.

The two presidential candidates are distinctly different. Juan Orlando Hernandez is a seasoned politician who assumed office in 2014. Despite a constitutional ban on re-election, Hernandez is running for a second term after a controversial 2015 Supreme Court overturn on the ban. Salvador Nasralla, on the other hand, is a television presenter who has been harshly critical of Honduran politics since the 1980s. In 2013, he dabbled into politics by founding the Anti-Corruption Party after being disillusioned with the corruption and inefficiency of the political establishment in the country. In 2017, he decided to run for President against the incumbent Hernandez. His candidacy quickly raised traction on his anti-corruption platform. During the first count of the votes, he enjoyed a 5% lead on his opponent. Nevertheless, as more polling stations were counted, the electoral commission–controlled by allies of Hernandez–declared an Hernandez win. Nasralla subsequently claimed fraud and has refused to accept the election results.

Had Nasralla won, his victory would have served as a further sign of the growing disillusionment with the political establishment in Central America. In 2015, Guatemala elected Jimmy Morales, a television comedian and self-styled outsider, as its president. He similarly ran on a platform of anti-corruption and anger against the political establishment against the former first lady, Sandra Torres. Meanwhile, both Daniel Ortega and Salvador Sanchez Ceren, became presidents after being guerrilla leaders in Nicaragua and El Salvador respectively. By going in favour of anti-establishment politicians, citizens have expressed loud and clear that they are done with the corruption that has become endemic across much of Latin America.

Corruption trends in the region more broadly are skyrocketing. However, Central American nations are perceived as being the most corrupt in Latin America. In the past three years alone, presidential corruption scandals have invaded the headlines in multiple countries in the region. In Panama, the former President Ricardo Martinelli was arrested in Florida on charges of embezzlement and illegal surveillance. In Guatemala, President Jimmy Morales and a shocking figure of 112 lawmakers are being accused of corruption. In El Salvador, the local civil court found that the former President Mauricio Funes and one of his sons enriched themselves with taxpayer money. In Honduras, President Hernandez has systematically bolstered the power of the executive branch while weakening other institutions during his last term as president. More recently, in a poll by Transparency International, 62 per cent of respondents stated that corruption had increased over the past year. The current election trends in Central America indeed show a growing disillusionment with the political establishment that is perceived to be corrupt.

With the possible Nasralla win in Honduras, the Morales presidency in Guatemala, Ortega in Nicaragua, and Ceren in El Salvador, the anti-establishment politics are ripe in the region. For long, corruption was seen as a normalized phenomenon. “He steals, but he gets stuff done” was the popular sentiment across the region. Today, multiple corruption scandals are deterring the little bureaucratic efficiency there was in government–the most prominent example being the Odebrecht scandal that swept across the continent. Odebrecht is one of Latin America’s construction giants responsible for massive infrastructure projects throughout the region from the Olympic stadiums in Brazil to the metro system in Caracas. In over 16 countries, Odebrecht bribed current and past government officials by offering them money for their election campaigns in exchange for building contracts. The scandal is considered one of the biggest corruption cases in history and its involvement ranges from ministers to presidents. From country to country, the scandal has brought to spotlight the negligence and corruption that has exacerbated the region’s inequalities.

Nearly all surveys of Latin America conducted by the AmericasBarometer , a periodic polling study of 34 countries in the Americas, have indicated that citizens hold their national legislatures and judiciaries in low regard. There is not only little trust in political leaders, but also in political institutions and liberal democracy. Disillusionment in the democratic system is due to the shortcomings and broken promises of politicians to their constituents which has driven many to vote for figures outside of the establishment. This, in turn explains the allure of populism to many as an attractive alternative prospect to the same old leaders. This populist revival is proof of the overall anti-establishment wave in the region. The Latin American Public Opinion Project (LAPOP) also found that young people are more likely to support populism and anti-establishment figures than the previous generation as they only know of the shortcomings of the current democratic institutions. Previous generations, however, have lived through the military dictatorships of the 1970s and 1980s and thus are less enthused. Seeing as the current median age in Latin America is approximately 24, we can see this reflected in how more young people are cast ballots.

The seductive prospect of the outsider-turned politician is not a new phenomenon in Latin America, but it has recently become increasingly salient. By 2016, Latin America has seen 13 presidents with minimal political experience in office since 1989. These leaders have ranged from military officers, recording artists, business tycoons, priests, and union organizers. The trend seen, however, is that once they are in office they turn semi-authoritarian, abuse and bolster the executive power, and turn corrupt themselves. Examples of these leaders abound in Latin America: Lucio Gutierrez in Ecuador, Hugo Chavez in Venezuela, Evo Morales in Bolivia, and Alberto Fujimori in Peru, among others. Gutierrez, president from 2003-2005, dismantled the Supreme Court as a statement of authority which brought Quito to a state of emergency that resulted in him being booted out of the presidency. Chavez, a former military officer, successfully managed to install an autocracy in Venezuela during his 14 year post as president by establishing control over the legislature, the Supreme Court, the armed forces, the National Electoral Council, and the state-owned oil company. Morales, the first Indigenous president of Bolivia and a former coca farmer, is seeking re-election after a controversial constitutional change which places no limits on re-elections. Fujimori, a University academic, established a “self-coup” with military support to dismantle Congress, suspend civil liberties and establish government by decree in 1992.

Not all outsiders, however, break their promise of change and turn corrupt. Former guerrilla member and president of Uruguay, Jose Mujica, donated 90% of his presidential salary to charity, lived in his farm rather than the presidential palace, and left the country in good economic shape and social stability. Nevertheless, Presidents like Mujica are rare in Latin America where outsiders and the political establishment often intersect in their greed for money and power. As we can see in these cases, these outsiders are hardly better than the political establishment and in some cases they are actively worse.

This new generation of anti-establishment politicians popping up in Latin America have capitalized on renewed hope for those seeking an alternative to corruption, favoritism, and inequality. However, what is apparent is that these leaders have not differed significantly from their predecessors. For instance, in Guatemala, President Morales was elected on a platform of transparency and intolerance for corruption and impunity. Nevertheless, last August he ordered Ivan Velasquez, the head of the United Nations-backed anti-corruption panel, to be expelled after the commission moved to investigate him. The actions of Morales illustrate the shortcomings of anti-establishment politicians who succumb to the same vices as previous generations of leaders. Another example of the anti-establishment not providing a viable alternative is the case of former president of Panama Ricardo Martinelli. Martinelli, who owns one of the country’s biggest supermarket chains, profited from posing as an outsider businessman to voters disillusioned in political corruption in the 2009 presidential elections. Voters wanted him to “to run the country as well as he manages his businesses.” Despite the hopeful sentiment of an anti-establishment president in office, he currently has over 12 cases in the Supreme Court of Panama, is being held in custody in Florida for corruption, and was voted third most-corrupt by a Transparency International initiative. Unfortunately, these examples are indicative of a growing corruption trend in the region that even the candidates and officials outside of the political establishment fall into. Even the ones that promise to change the rules of the game are lured by the prospects of money and power.

In the next two years, fourteen Latin American countries will head to the polls and one thing is certain: low tolerance for corruption and diminished trust in the political class will profoundly affect the results of the upcoming electoral cycle. “If the rules of the game don’t change, then the fight against corruption will not bear fruit,” said Iván Velásquez, leader of the International Commission against Impunity in Guatemala. Latin America aches for a process of political reform, political cleansing, and reformation. If the rules of the game do not change, the chances of achieving improvement seem dim. With the anti-corruption wave that is sweeping the region, one can only hope that leaders will more closely adhere to principles of transparency under growing calls for accountability on the part of the Latin American citizenry.

Edited by Luca Loggia