The Colonial Roots of Zuma’s Presidency

Jacob Zuma, Apostle Simon Mokoena, and Zulu King Goodwill Zelithini ka Bhekuzulu - seated like royalty - at the Annual Sons of Zion Conference of Tyrannus Apostolic Church. https://flic.kr/p/dCCw99

Jacob Zuma, Apostle Simon Mokoena, and Zulu King Goodwill Zelithini ka Bhekuzulu - seated like royalty - at the Annual Sons of Zion Conference of Tyrannus Apostolic Church. https://flic.kr/p/dCCw99

The reputation of South Africa’s president, Jacob Zuma, has gone steadily downhill since the country began “flirting with recession” in 2016. The extent to which Zuma is responsible for South Africa’s current economic “junk status,” however, is widely debated – especially given various environmental crises and the impact of China’s economic slowdown. Nevertheless, his frequent misuse of public funds and criminal charges of undemocratic use of power have gained him sharp public criticism. After receiving 783 criminal charges, the public saw his decision to fire Pravin Gordhan as the last straw. After the well-loved former finance minister was sacked on March 31st, people across the country began protesting and demanding Zuma’s resignation. This ongoing resistance effort is seen to be the largest uprising since the Anti-Apartheid Movement (AAM) – and the protests evoke similar rhetoric. “Songs of the revolution” are often chanted as protesters fight to “represent what [their] parents fought for” and reconfigure the country to resemble the unified South Africa they saw just after independence. This is a complicated goal, though, considering the party largely responsible for dismantling Apartheid is the same one that is currently backing Zuma.

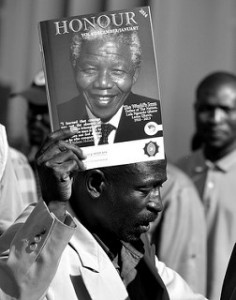

South Africa’s system of apartheid lasted from 1912 to 1994 and its dissolution is largely credited to the African National Congress (ANC), once led by Nelson Mandela. As such, the party became a symbol of pride and a source of unity for the country. However, the rupturing of the ANC, signaled by the protests, has also shed light on the effects of neocolonialism in independent South Africa. Pointing out Zuma’s presidential misconduct and recognizing how his actions have damaged the now-faltering South African economy are both necessary and easy. But blaming South Africa’s problems solely – or mainly – on Zuma misses the ways that colonial capitalist practices carried over as the ANC rose to power in 1994. The party knew that revolutionary vigor alone could not sustain the newly independent country. Instead, aspects of colonial capitalism were kept intact as relationships with conglomerates such as the mining group Anglo-American, which, under the new regime, was “not only allowed to exploit black workers but [was] shielded from competition.” Officials such as Nelson Mandela were left very, very rich. The ANC then attempted to build a Black capitalist class, but due to the economic exploitation of apartheid, independent South Africa was not left with the capital to do so. With a damaged economic framework and a party that did not aim to drastically alter the prior economic order, inequality prevailed through neocolonialism. The current protesters, however, peg Zuma as the main problem and the election of a new ANC president as the solution, but the factionalism and intergenerational patronage Zuma represents can be traced back to colonialism. It is ineffective, therefore, to protest on the lines of past revolutionary rhetoric. Despite South Africa’s post-independence stability, extensive colonial exploitation left the ANC with major hurdles that cannot be solved with band-aids. Political ideologies, therefore, must be created after conducting an extensive analysis of the institutionalization of neocolonialism. As such, South Africa needs innovative political frameworks – and a new public debate on how they can align themselves with the country’s economic goals.

For many South Africans, the firing of Gordhan became the defining moment that brought all of Zuma’s misgivings to a front – without necessarily seeing the colonial roots of these problems. President Zuma’s notorious reputation for cabinet reshuffling –having fired four finance ministers within two years– has earned him a wide range of supporters and detractors. After Gordhan was fired, opinions of him were divided more concretely as the tripartite system of the ANC came out with diverging public statements. Zuma is currently backed by the ANC, while the Congress of South African Trade Unions (COSATU) and the South African Communist Party (SACP) are calling for his resignation. These divisions are further complicated considering that some ANC officials have been the most prominent denouncers of Zuma. Others publicly condemned his decision to fire Gordhan but continued to support him nonetheless, leading the public to view South African politicians under an increasingly skeptical light.

The public is also split over Zuma, revealing a demographic divide that highlights colonial legacies. Many Zuma supporters are part of the rural population; most detractors are city dwellers. Under apartheid, rural sectors were especially disadvantaged economically, socially, and politically; migration restrictions further alienated them from urban centres, and the subsequent inaccessibility to education left rural dwellers few opportunities to politically combat colonial rule. Given South Africa’s rapid urbanization and pervasive economic inequality, the gap between the urban and the rural remains. For those living in abject poverty, the current legal disputes can seem remote in contrast to the radical transformation the population still hopes for. Zuma promises them this radical transformation, constantly telling the rural population he will eradicate poverty for the Black majority. Another factor that contributes to the demographic divide is the fact that Zulu peoples, who make up a quarter of South Africa’s population and who live mainly in rural regions, “culturally identify” with Zuma. The president often rhetorically draws on “ethnic politics” to mobilize the rural population.

The ANC’s rural influence creates another obstacle for Zuma protestors and impedes their ability to achieve a unifying vision. Given the continued unequal access to political education, the rural population’s battle faces much larger issues that cannot be solved by dethroning one politician. Both supporters and detractors of the ANC are utilizing anti-apartheid rhetoric in their struggles, but neither side has put forward an innovative ideology to create a new image of South Africa’s future. The AAM was driven by African nationalism, social democracy, black consciousness, and an opposition to racial segregation. The movement also gained international recognition and support through academic and consumer boycotts, as well as economic sanctions against the apartheid system.

In contrast, today’s protests lack a clear vision and thus advocate a look to the past. Their target, furthermore, is not fully agreed upon. Those who believe that Zuma must go have divergent suggestions for what should proceed afterwards: some believe Zuma must simply step down and be replaced by someone who will reconfigure the ANC and follow its mandate; others believe the party, in its current framework, is unable to be reunified. Without a clearly defined movement, most of the protests have focused on broad, ambiguous goals: they are framed as a “battle against corruption” in order to achieve “good governance.”

Both major opposition parties, too, believe Zuma must go: they have clearly stated why they believe he should leave, but have failed to offer any tangible ideas for what South Africa’s future will look like afterwards. The Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF), to the ANC’s left, and Democratic Alliance (DA), to its right, are the main opposition parties to the ANC. They have also shown their presence at protests, although they garner less attention than other civic organizations such as “Save South Africa,” which includes aggravated members of the ANC. Like Zuma, these parties have faced their share of controversies, allegations, and charges, making it difficult to mobilize one dominant resistance movement. Their strategies largely consist of critiquing Zuma, without innovating new discourse which would allow the population to rethink South Africa’s future. The protests, thus, have been waged under many different political and non-governmental names, resulting in increased political tension and division within the movement.

As protests increase –in both size and violence– and as Zuma continues to postpone the vote of no confidence, the future of the ANC and South Africa appears uncertain. Many believe Zuma is trying to prolong his time in office in order to have greater influence over his successor. Plans are currently being set in place to appoint his ex-wife, Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma, as the next president. Many see this move as another instance of veritable intergenerational patronage despite ANC claims of upholding democracy. Throughout his presidency, Zuma has manipulated the ANC’s rules and regulations to achieve power, and the party has been unable to hold him accountable. In the case of Gordhan, no ANC officials were consulted nor notified before he was fired. Afterwards, the ANC did not formally denounce Zuma’s tyrannical decision-making process. Despite the party’s revolutionary beginnings, generations of corruption, and difficulties in combatting said corruption are leading many to question if the ANC’s framework will be able to create and sustain democratic measures.

A few years ago, debating the ANC’s relevance would be unthinkable. The party, led by Mandela, was quite literally thought to be “anointed by God.” Its multiracial judicial system and free elections were seen as revolutionary both locally and internationally. Over time, however, the ANC’s innovative ideas on decolonization and human rights improvement diminished. As the revolutionary spirit faded, people began losing their faith in the ANC as it failed to produce the change it promised. This has led to the ANC losing its grip on the popular vote. In the last election, they lost control of Pretoria, where they had previously won by a majority of 66%.

As the political centre is challenged, left- and right-wing populists are emerging to reconfigure the political landscape; new ideologies are introduced, along with economic reforms. We have seen this recently in countries such as the United States, Britain, France, and Greece. In South Africa’s case, though, the proposed solutions seek to reconfigure current state institutions to resemble an image of South Africa upon its eve of independence. Comparisons between Trump and Zuma are already circulating, as both figures draw on nationalist sentiment to agitate the population. Through unattainable visions of the past, both populations have been emotionally manipulated to believe that things were better back then, and that the country’s problems could be solved through time travel. While it’s important to recognize that, in South Africa’s case, the country was making significant strides in human rights and economic growth, aspects of the colonial framework still pervaded – even in the ‘good old days.’ Thus, South Africa needs a new ideology that would respect, understand – but ultimately break from – the past.

However, many question if such an ideology is attainable given the current state of the ANC: without a vibrant ideology and perseverant solidarity and in the presence of the entrenched systems of patronage and loyalties, the party’s democratic principles have been compromised time and time again. Marxist-Leninism, Pan-Africanism, and Frantz Fanon’s theories of decolonization must come back into the public debate – but they must also regard current local and international contexts, alongside persistent colonial legacies.