Dirty Money, Dirty Water: Oil on Trial in the Amazon

On April 7, 2020 members of the Indigenous communities of Ecuador’s Amazon suddenly found themselves in the midst of a second major health crisis, occurring in tandem with the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. That morning, Petroecuador, Ecuador’s state-run oil company, reported the rupture of two major oil pipelines in Ecuador’s northern Amazon, spilling oil directly into the Coca River and eventually contaminating the Amazon River in Peru. The spill was first reported as only 4ooo barrels of crude oil, a gross underestimation by the Ecuadorian government. It has since been revealed to have been more than 15000 barrels, making it the largest oil spill to occur in Ecuador in more than a decade.

The rupture, caused by a landslide, came as no surprise to the communities whose survival has long relied on access to the Coca River. The river, and its surrounding area, is a known hub of seismic activity that has become more unstable through years of poorly constructed oil infrastructure projects. One of the pipelines involved in the spill was Ecuador’s Heavy Crude Pipeline which was constructed in 2001. The construction of this pipeline took place in spite of protests from Indigenous groups and scientists warning of catastrophic consequences as it crosses multiple fault lines and active volcanoes. Furthermore, since the construction of a Chinese government-funded hydroelectric dam was completed in 2016 in the same Coca River, geologists and hydrologists have warned that the area would face further erosion, leaving the pipelines at increased risk for rupturing. The Ecuadorian government owes more than $19 billion in loans to China for the construction of the dam along with several other oil infrastructure projects and plans to pay the vast sum of it back with oil. Because of this severe financial burden, Ecuadorian officials ignored warnings and went ahead with the construction of the pipelines, putting the lives of thousands in jeopardy. Since the construction of the dam, there have been 72 spills.

Following the events of April 7, over 2000 Indigenous families have been left without access to basic food and clean water, conditions that have only worsened following the Ecuadorian government’s insufficient attempts to clean up the area. Not only will the resulting contamination translate to physical loss in the form of sickness and hunger in communities already hurting from the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, but the Coca and Napo Rivers also have deep cultural ties for the Indigenous communities of the Amazon, leaving much to be mourned. The rivers are home to aquatic species like the anaconda, which has long served as a spiritual protector for communities like the Siona and Waorani People of Ecuador. These species are now at risk of extinction because of the ongoing exploitation of their habitats.

On April 29, several affected Indigenous families along with organizations including the Ecuadorian Alliance for Human Rights, the Confederation of Indigenous Nationalities of the Ecuadorian Amazon (CONFENIAE), and the Kichwa peoples’ Indigenous federation (FCUNAE) filed a lawsuit against Petroecuador and OCP Ecuador, the management company for the privately-owned Heavy Crude Pipeline. The central claim of the plaintiffs is that “the oil spill has violated their constitutional rights to territory, health, information, water and food sovereignty, a clean and ecologically balanced environment, and the rights of nature”. The lawsuit also points out the continued irresponsibility of the Ecuadorian government in ignoring warnings from scientists about severe erosion along the river and failing to properly protect the affected families. Proceedings of the trial began in late May over Zoom but have since been suspended by the judge, who cited possible symptoms of COVID-19. Already a questionable excuse, being that the trial is taking place virtually, the judge only suspended the trial once it was time for the Ecuadorian government to present their evidence and seemed to ignore the obvious time sensitivity of the issues at hand. In the two months since the arbitrary suspension of the trial, erosion has only worsened along the Coca River with several new landslides occurring near the pipelines. Currently, affected families still remain without access to adequate food and clean water.

Oil is Ecuador’s main source of export revenue. As such, it is often seen as the last hope for economic recovery. According to the country’s Energy Minister Rene Ortiz, and in spite of the consequences for Indigenous communities, the country does not plan to alter the amount of oil it exports following the spill. Since even before the construction of the pipelines both Indigenous activists and environmentalists have made it known that potentially fatal consequences were inevitable if the Amazonian oil industry continued to operate as it has for the past few decades. Yet, determined to cater to the demands of the international oil market, both state and private companies choose to continue to perpetuate harm against the country’s Indigenous communities, ultimately valuing profit over human life.

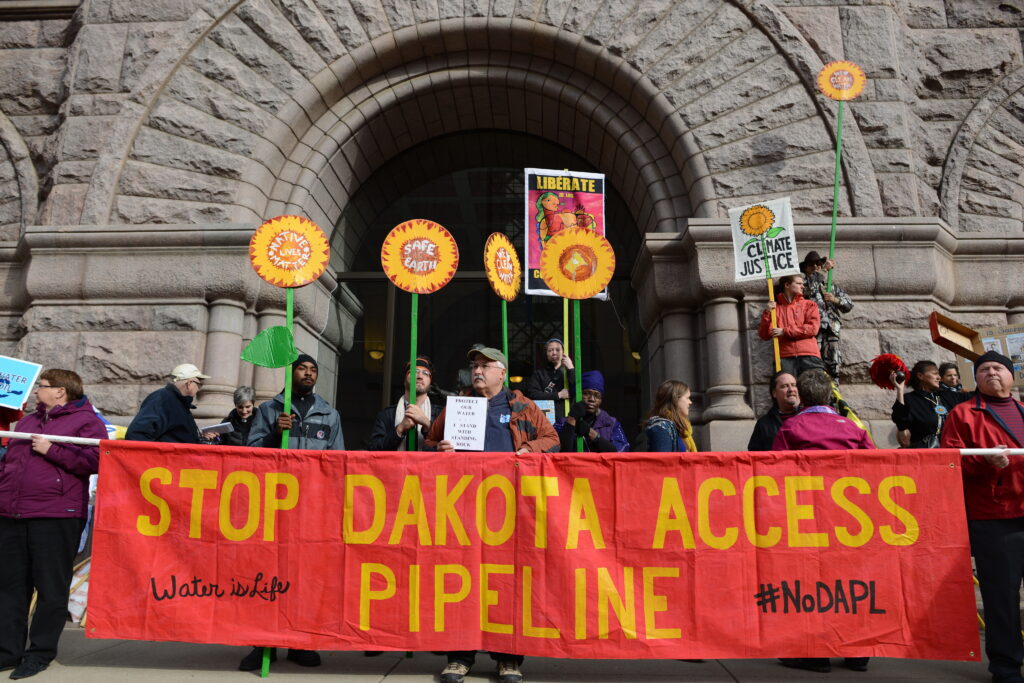

Media coverage of the spill and ongoing lawsuit has since been overshadowed by news of the shutdown of the controversial Dakota Access pipeline, which runs through four US States and crosses the Missouri River, a key source of water for the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation. On July 6, US District Judge James Boasberg ordered the pipeline’s operator, Energy Transfer LP, to halt operations and empty the pipeline within 30 days. This decision is a victory on the part of Indigenous activists who had protested against it for years citing risks of water contamination and destruction of sacred areas. However, it is important to remain attentive to the delicacy of the situation and its international context.

Since Judge Boasberg’s initial decision, Energy Transfer along with its supporters appealed the shutdown and may be allowed to continue pumping oil through the pipeline pending the decision of a higher court. This appeal shows how imperative it is to ensure that justice-seeking efforts are more than symbolic. It is far too easy for distanced bystanders without personal stakes in these battles to read headlines about shutdowns and blindly accept victory. Popular acceptance of international oil companies’ superficial morality indicates a blatant ignorance of the years of physical, spiritual, and legal losses suffered by families of the Ecuadorian Amazon. Even if a higher court upholds the shutdown decision in the US, it is doubtful that this trend of justice will reach the Indigenous communities of the Amazon. The story that these communities have seen play out for decades is such that environmental and humanitarian successes in North America do not translate to justice for all. Instead, the companies and courts praised for listening to public outcry are often simultaneously contributing to the harm being done in the Amazon in the name of oil extraction, ultimately echoing a continued global trend of placing economic flourishing over human life.

Featured image: “Texaco’s signature – Lago agrio” by Julien Gomba is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

Edited by Maëna Raoux