Evicted Development: Moving People for Pipelines

Fifteen years ago, UK company Tullow Oils began drilling in Western Uganda, discovering the country’s previously untapped oil reserves. Today, two other international oil giants are collaborating with East African governments in a slow, tactful land grab to take advantage of them. Construction of the East African Crude Oil Pipeline (EACOP) is set to begin next year — and it’s likely the biggest pipeline you have never heard of.

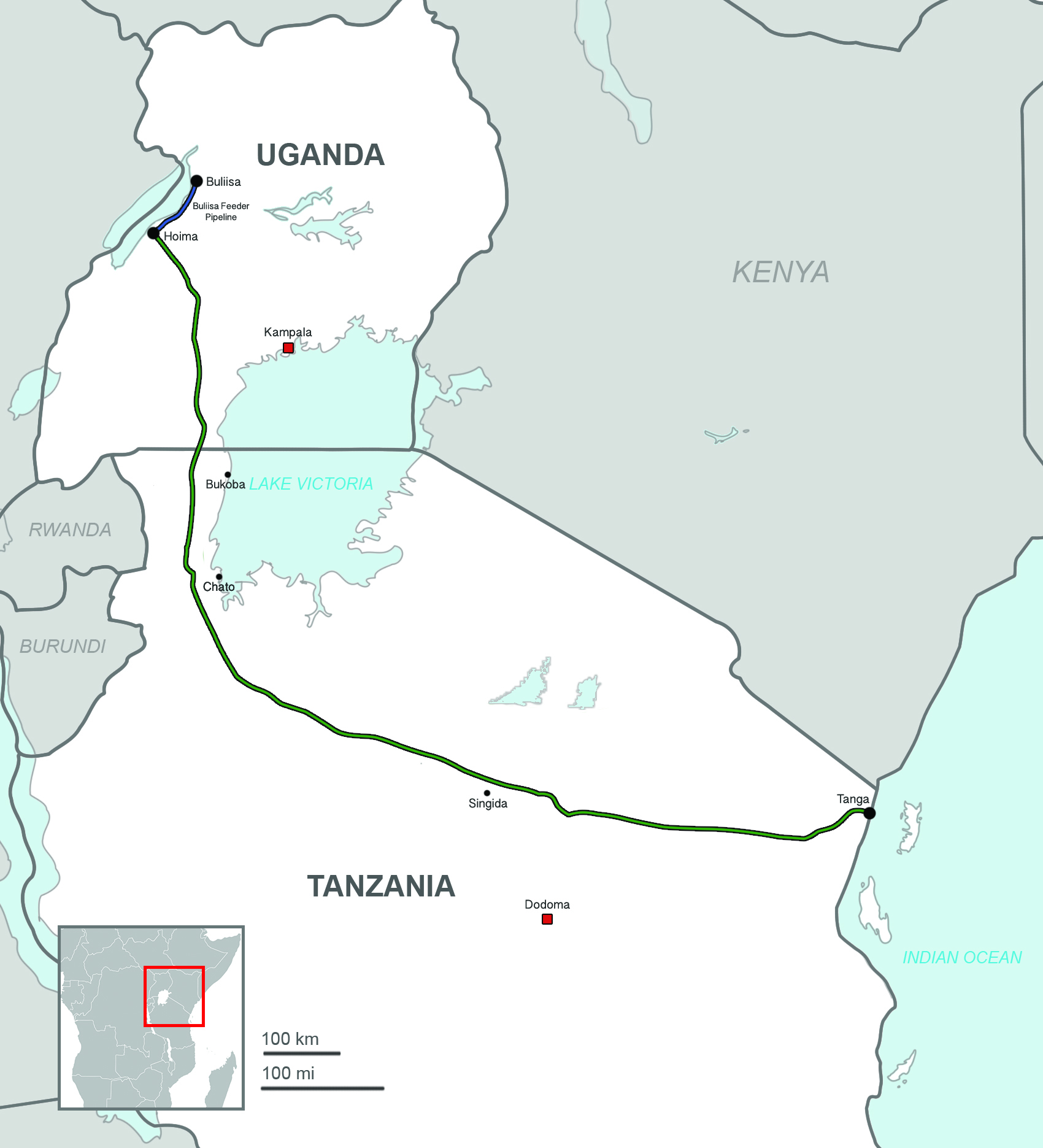

The EACOP is a project started by French oil giant Total and China National Offshore Oil Corporation (CNOOC). If completed, it will be the world’s longest heated oil pipeline, stretching 1,440 km long from Uganda’s Lake Albert to Tanzania’s port city, Tanga, alongside Lake Victoria. The pipeline poses a significant ecological threat to Africa’s largest lake and the numerous other biodiverse areas it will cross, leading to the planned displacement of hundreds of families. Partial land seizures and ecological degradation will impact thousands more as governments and multinational corporations prioritize “development,” or capitalist enterprise, over local livelihoods.

The project

The people of Western Uganda’s Bunyoro Kingdom knew about the presence of oil in their region long before Tullow Oils arrived. However, until drilling began, they didn’t know that the largest onshore oil deposit in Sub-Saharan Africa was located on the shore of Lake Albert, straddling the border between Uganda and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. During preliminary discussions about how to best use Uganda’s oil reserves, Total, CNOOC, and other interested parties rejected Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni’s initial suggestion for a domestic refinery that would primarily benefit the Ugandan economy. Instead, they proposed a pipeline that would allow for commercial production. The EACOP is intended to connect the Lake Albert oil fields to Tanzania’s Indian Ocean port, facilitating land-locked Uganda’s capacity to export to international oil markets — all but ensuring multinationals Total and CNOOC will get the highest payout.

Despite corporate stakeholders’ attempts to de-emphasize East African governments’ best interests, both Museveni and the late, former Tanzanian president Joseph Pombe Magufuli identified expedited construction of the pipeline — and all accompanying land acquisitions — as national priorities. The EACOP’s website contains a section dedicated to how the pipeline will help “[unlock] East Africa’s Potential,” listing job creation, increased business opportunities, infrastructure development, and “potential for oil exploration” as ways the pipeline will supposedly help develop the region into “a preferential business hub.” These purported benefits all fulfill the energy goals outlined by the Ugandan government in policy statements from 2002 and 2008: “to ensure the sustainable utilization of discovered petroleum resources to contribute to early achievement of poverty eradication and create lasting value to society.” Political figures like President Museveni tout these outcomes as positives. In reality, the local and global costs of biodiversity loss, large-scale resettlements, and increased carbon emissions will soon outweigh any potential economic benefits of new oil exploration in East Africa.

Land grabs: past and present

A 2020 Oxfam report estimated that the land acquisitions needed to construct the EACOP would imply the full relocation of over 200 households in Uganda and 391 in Tanzania. These numbers do not include the inevitable economically-induced displacement of the thousands of households expected to lose smaller portions of land, hindering their access to subsistence agriculture and other land-based livelihood practices.

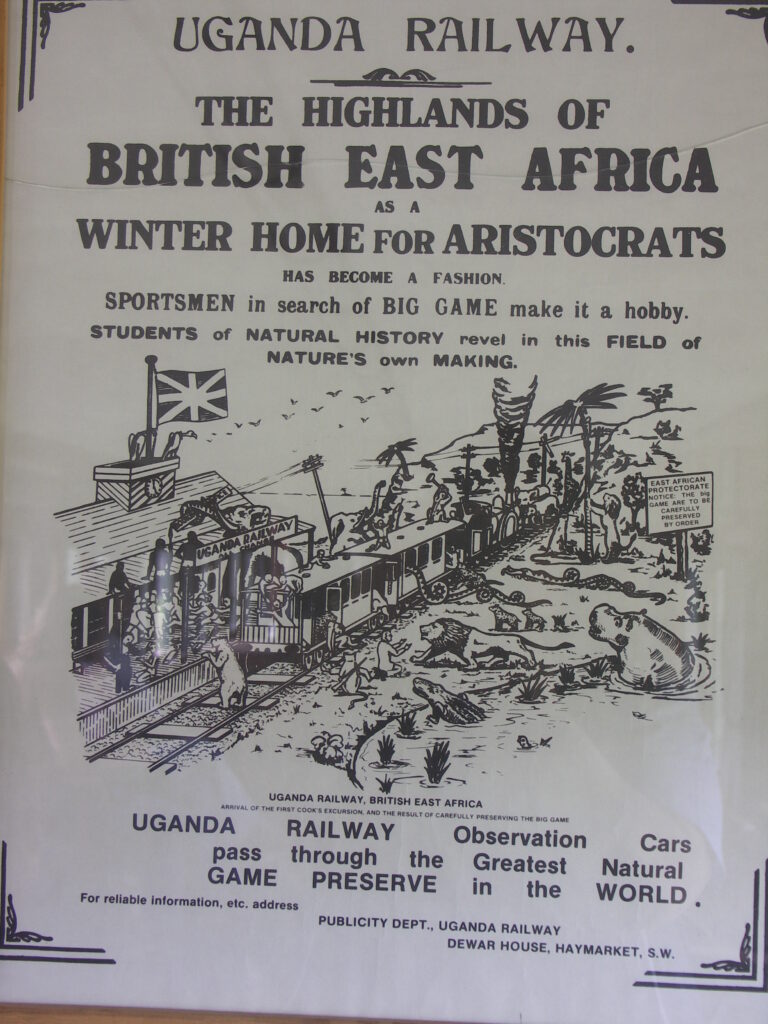

Government-mandated land acquisitions and resulting mass-displacements echo another period in Ugandan history: the creation of Protected Areas (PAs) under British colonial rule. The fortress model of wildlife conservation, introduced by Western colonizers, involved adjudicating certain portions of land and resources to government control, notably without community consent. Conservation, like development, still retains a reputation as a marker of progress amongst most global powers. However, the creation of PAs under colonial governments was a process intended to benefit white colonizers exclusively. Wildlife inside Protected Areas was marketed as a spectacle to draw in tourist revenue through safari tours and hotel stays. Still, that revenue wasn’t going to the communities that were forced out.

While Uganda has plans to provide financial compensation and resettlement assistance to the families displaced by the EACOP, the project will displace many communities from their ancestral lands. It is a distinctly Western philosophy to conceive land as something made for exchange rather than use and appreciation. Colonial governments operated with the same conception when they created Protected Areas. In both cases, offering communities compensation in the form of new plots of land or payments does little to mitigate the cultural, generational, and ecological damage caused by displacement. Property rights are included in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which explicitly states that “no one shall be arbitrarily deprived of [their] property.” But, history has repeatedly shown that when land is commodified — a common symptom of “development” — people are forced off of it. Not only are displacements of any kind inherently violent, but they also divorce people from their livelihoods, thus increasing job insecurity, food insecurity, marginalization, and mortality rates.

A new scramble for Africa?

Oxfam’s 2020 impact assessment of the EACOP concluded that the environmental and social risks posed by the project “can become serious and systemic human rights violations that exacerbate inequality and poverty if not appropriately addressed or managed.” Yet, corporations, governments, and economists across the globe still promote claims that projects like massive new pipelines are helping the communities they displace. A 2019 article from the Economist, titled “The New Scramble for Africa” about the colonial division of the continent in the 19th century, discussed the recent growth of foreign interest in the continent’s oil and mineral reserves as a good thing. It included a statement that “if Africa handles the new scramble wisely, the main winners will be Africans themselves.” These sentiments echo those that drove colonization back in the 19th century: the idea that Africans needed to be saved from themselves.

The irony of the situation is that goals of “development” are hindering global progress. As nations strive to meet the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals, there is a widespread failure to recognize that most “development” plans are still maintaining the global distribution of power and resources status quo. Projects like the EACOP are not just being implemented to “unlock” the potential for countries like Uganda to reach middle-income status — they’re making their resources easier to exploit. The world’s most powerful actors are once again sidelining livelihoods and wildlife to protect their interests, under progressive-sounding labels like “conservation” and “development.” As with the creation of the PA system, foreign corporations and development agencies are once again acting as proxies for world powers, scrambling to claim their stakes on the African continent and access to its resources.

Featured image: “The Lake Albert Hotel near Buitaba” by Matson Photo Service is licensed by the Library of Congress.

Edited by Sara Parker