The Forgotten Conflict of Burundi

https://www.flickr.com/photos/un_photo/3332077082/in/photolist-65rLqS-8gJzeE-8gFi3M-GZuWy-9CZfQN-8gJzSh-8gJzEA-GZaHg-9E3z6f-7dDPQS-7b9D6o-6pmuVB-6pqDpf-GZyzp-GZDyy-9UDCPJ-GZbzv-GZsGi-8gJzq1-GZwqX-8iuYB-8musRx-GZbGg-GZfva-GZvmQ-9DZGqM-6pqDsd-9E3zfJ-GZDai-6vT5P6-9UALyk-GZr3v-9SQqSS-GZBbQ-9jwwjB-9jzAfq-GZe1G-2ynD7X-2ynmij-GZA6B-GZoss-9jwxWX-GZytR-4M9xaP-GZFtP-GZtAL-GZsjJ-8mRHm3-GZxNJ-2yt4Tg

https://www.flickr.com/photos/un_photo/3332077082/in/photolist-65rLqS-8gJzeE-8gFi3M-GZuWy-9CZfQN-8gJzSh-8gJzEA-GZaHg-9E3z6f-7dDPQS-7b9D6o-6pmuVB-6pqDpf-GZyzp-GZDyy-9UDCPJ-GZbzv-GZsGi-8gJzq1-GZwqX-8iuYB-8musRx-GZbGg-GZfva-GZvmQ-9DZGqM-6pqDsd-9E3zfJ-GZDai-6vT5P6-9UALyk-GZr3v-9SQqSS-GZBbQ-9jwwjB-9jzAfq-GZe1G-2ynD7X-2ynmij-GZA6B-GZoss-9jwxWX-GZytR-4M9xaP-GZFtP-GZtAL-GZsjJ-8mRHm3-GZxNJ-2yt4Tg

Burundi, an African country located in the region of the Great Lakes, is going through a worrying crisis rapidly deteriorating into a civil war, opposing the government to its population, since April 2015… but no one is talking about it.

In April 2015, Burundians took to the streets of Bujumbura, their capital, to protest against Pierre Nkurunziza running for a third mandate. President for now a decade, Nkurunziza’s decision to run for president once more is a clear violation of the Burundian constitution, which limits presidential mandates to two terms. The government opened fire on its people protesting, and the political campaign has been marked by violence and repression since then. Over the course of one month, 70 people had lost their lives, some while protesting, others assassinated as government workers. In May, a failed coup d’état further rattled the already paranoid and threatened executive, causing the president to operatd in terms of survival and maintenance of the regime as a whole.

As seen through the violent clashes between Burundian citizens and presidency, a rhetoric of “it is either us or them” is prevalent. This mindset of dire cleavages and constant conflict explains the abuse, violence and intimidation present today in Burundi.

Over the course of 2016, independent local medias have disappeared, and the National Service Intelligence, an instrument employed by the government to surveil the population, has tortured opponents of the regime. The Ruling Party Youth League Members: the Imbonerakure have committed atrocious crimes and terrorised civilians. At this point, it is estimated that 700 people have been killed, between 600 and 800 have disappeared, 5000 have been arrested, from which only 2000 have been released.

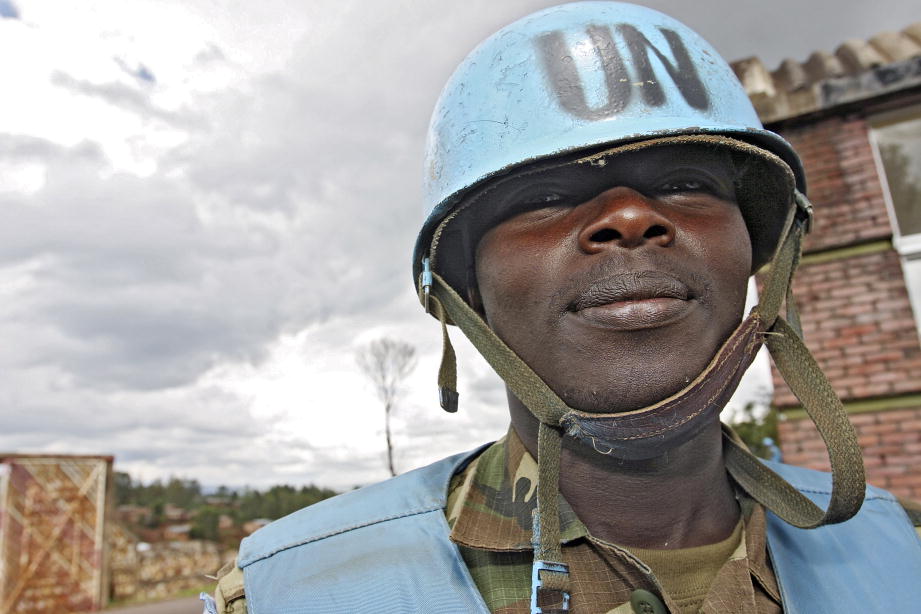

Throughout these periods of violence and war in Burundi, the trend we notice is Nkurunziza’s government’s slow move to isolating itself from the rest of the world. After the International Criminal Court opened an investigation of Burundi for “human rights abuses,” the government decided to withdraw from the court, in spite of the population opinion to remain a signatory of the Rome Statutes. Bujumbura refuses to negotiate with the African Union. It has refused any UN intervention, and has stopped working with the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, after the latter filed a report in September 2016 condemning the modes of operation of the regime. On top of these facts, journalists, both local and international, are not welcomed.

The fact of Burundi’s increasing diplomatic isolation is further troubling given the serious humanitarian crisis that has already crossed the borders. More than 300 000 Burundians have fled to neighbouring countries, with Tanzania and Uganda welcoming the majority of them. The director of the African department of the International Federation for Human Rights (IFDH), Florent Gheel, estimates that 80% of the civil society has left the country. Through the use of the Imbonerakure, Bujumbura is strengthening the borders, hoping to stop citizens from fleeing and, in-doing-so, to limit the international attention that a refugee crisis could bring to Burundi. Thousands of Burundians are reported to hide in their own country in hope to escape the violence of the regime. The local economy is crippled, and foreign aid that Burundi used to receive has been suspended. The population is already experiencing the early signs of malnutrition both in Burundi and in the refugee camps, which can barely handle the influx of 10,000 Burundians per month. Local organisations are lacking the needed resources and the UN agencies mentioned how they managed to raise only a tenth of what should be necessary to tackle the crisis.

The crisis that had originally started as a political upheaval solely, is slowly evolving into a conflict tarnished by ethnic rivalries. In its paranoia, the mostly Hutu government is framing its actions along ethnic lines, which forced Paul Kagamé to publicly condemned Burundi’s leaders and to be mindful of the painful history shared by both of their countries. Burundi’s old demons are indeed coming up the surface. The country is still shaken by the last conflict (1993-2005) opposing Tutsi to Hutu, costing the lives of 300,000 people. Since the end of the conflict however, Burundians regardless of their ethnicities were peacefully living alongside eachother, and assured that the political upheavals of the 2015 crisis were only political. But the ethnical dimension of the conflict can no longer be denied, as UN workers report on ethnic crimes. Refugees in Uganda and Tanzania have testified they had to leave Burundi, not for protesting against the regime: they were soldiers of the national army, but because they were Tutsis. The conflict is thus no longer only a matter of political rivalry, since even members of the main enforcement instrument of the party, fear for their security based on their ethnicity.

Burundi’s situation is showing no signs of improvement and the truth is that there is a high risk for it to become regionalised. Thierry Vircoulon rather provocatively describes Burundi as a geopolitical bomb. With its economy slowing down, its population fleeing and the whole region still marked by the rivalries between Hutu and Tutsi of the 1990s, Burundi’s conflict will have an impact politically and economically on the region. Some tensions have already been observed between Kigali and Bujumbura, with Rwanda suspected of welcoming the Burundian opposition and recruiting Burundian rebels among the refugees

The role of the international community is not limited to the United Nations and other international organizations, especially when like Burundi, the country in conflict is diplomatically isolating itself. It includes the attention of other civil societies as well, which is relayed by their access to worldwide information. When international civil societies are mobilised around a cause, they can exercise enough pressure on governments so they at least reengage in diplomatic negotiations. Medias play a crucial role in that process. They are the one expected to raise awareness on events around the world. One can think of South Africa under the apartheid regime as an example. It is indeed notably through the mobilisation of international civil societies campaigning against the discriminatory government, that the measures put in place by the UN revealed to be successful.

However, the societal bias of only caring about what affects oneself directly can hinder the external political pressure that international societies should put on the government. It is clearly put in display with the Burundian crisis through the lack of news on the topic. Nonetheless, raising awareness about the Burundian conflict could help local actors regain legitimacy against their oppressing regime and help local organizations tackle the lack of resources needed to help the population. Nkurunziza is trying to undermine the gravity of the crisis, and he is being helped in this regard when no one reports on his actions and on Burundi’s current situation.