The Global Burden of Disease: Use and Abuse of Health Metrics

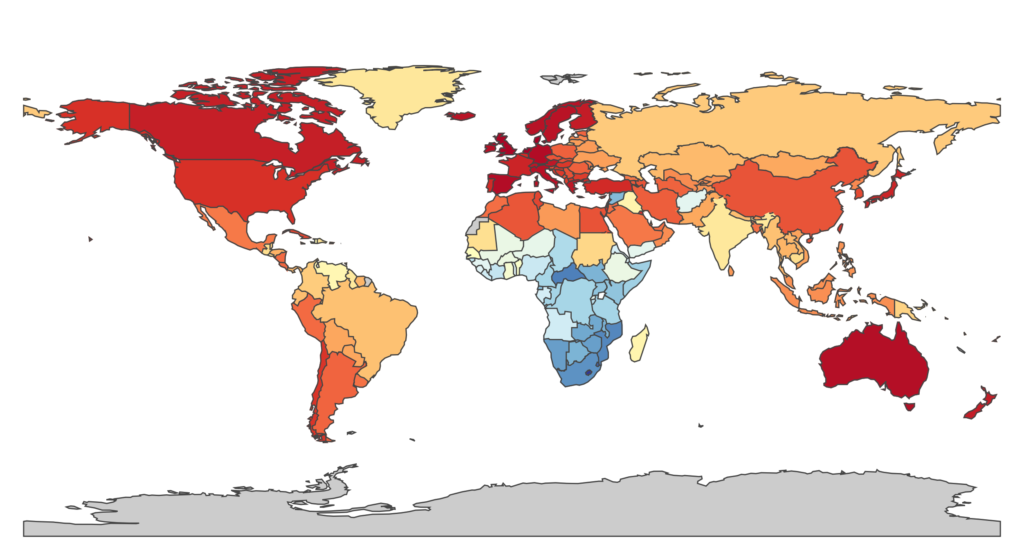

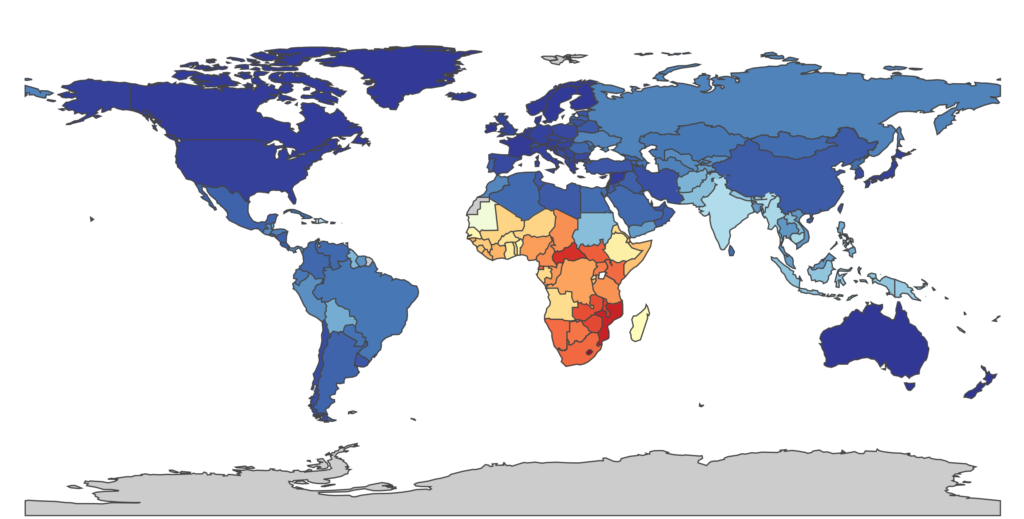

Three decades ago, the introduction of the Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) into the human population sparked one of the largest public health crises in known history. Today in the Western nations, the global fear brought on by HIV is now largely forgotten in the public mind as a result of the development of antiretroviral (ARV) treatments for infected people. HIV is no longer the death sentence it once was. Developed nations, in particular, have a bountiful infrastructure and a wide availability of newly licensed HIV drugs – developing nations, by and large, do not. This is just one example of the broader picture: the prevalence and transmission of many diseases can be attributed to, among many other things, the existing health disparities and social inequalities within and across borders. In high-income countries, the leading causes of lost years of life are mostly due to chronic diseases: ischemic heart disease (IHD) and respiratory infections; in the global South, the story is much different (HIV is still a leading cause of illness in sub-Saharan Africa). And where it was once established that infectious diseases were the main source of illness, we now regard the leading sources of illness to be non-communicable, chronic diseases: IHD, mental illness, cancers, stroke, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

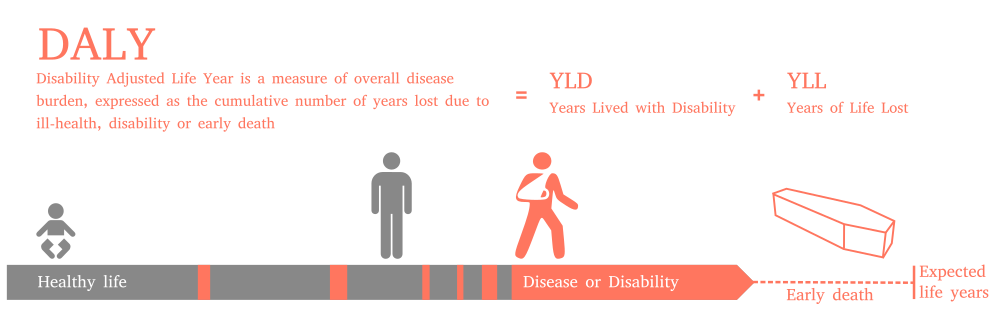

These differences are largely due to the statistic that represents them: the disability-adjusted life year (DALY). The DALY is a single measure of cumulative mortality and morbidity (a diseased state; the presence of a potentially non-fatal disease that affects the life of an individual) for a specific disease used to compare life expectancy across the globe and to quantify human illness in a reliable and consistent manner. In other words, the DALY, calculated for a single disease, accounts for both the years of life lost due to premature death caused by the disease and the years of life lost due to disability of living with the disease and enduring its consequences (the latter makes use of disability weights calculated by either a panel of experts or surveys). It makes comparable any two completely distinct diseases and is used in the priority-setting of many current global health efforts.

Though the DALY was originally developed in the 1990s by researchers at the World Health Organization [1], it has only recently gained attention through its use in the science giant of the modern public health world: the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) study. Today, DALYs and the GBD are staples of global health research. Indeed, a quick search for “global burden” on Google Scholar yielded over 2.2 million results: the global burden of stroke, the global burden of hypertension, the global burden of cancer, the global burden of surgical diseases, the global burden of viral hepatitis, the global burden of diabetic foot ulceration … the list goes on.

The explosive popularity of this domain of public health can be attributed to its leading pioneer, Dr. Chris Murray, co-developer of the DALY and founder of the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) based out of the University of Washington in Seattle. The IHME spearheads the GBD project, providing in its own terms a “rigorous and comparable measurement of the world’s most important health problems.” The project was so impressive that it attracted the attention of the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, who offered a $105 million dollar donation to the founding of the institute. The IHME depends on the DALY for its calculations, producing what has been called “the most comprehensive review of the state of humanity’s health ever undertaken.” It is certainly one of the most transparent quantitative measures to date: the IHME hosts a series of interactive data visualizations on their website for the public to explore.

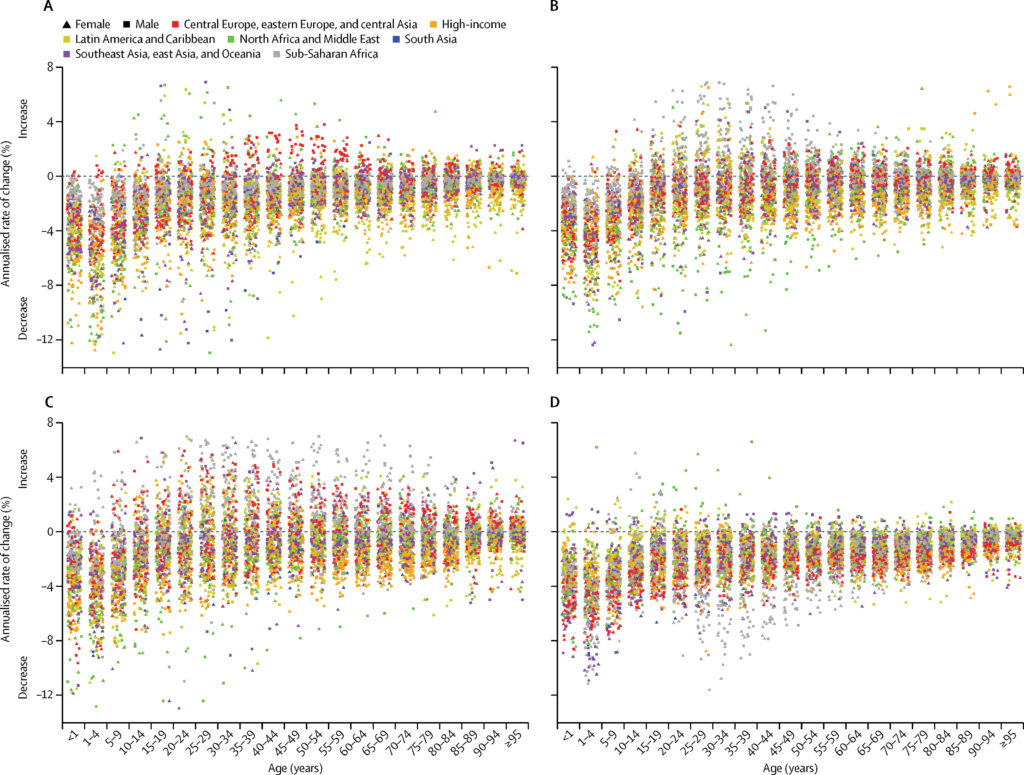

As ambitious and important as this project is, there have been and still exist residual issues. Upon its release, the 2010 GBD study was heavily criticized for its methodology related to the assignment of different disability weights to different age groups and the different life expectancies between sexes. The study team took these criticisms seriously and diligently made revisions. More recently, critics have also targeted the manner in which the GBD study determines disability weightings for different diseases. Disability weights are used to represent the severity of a disease condition, standardized between 0, denoting full health, and 1, which denotes death. Non-fatal outcomes lie in between the two: for the GBD 2013 study, hearing loss was given a weighting of 0.033, while neck-level spinal cord lesions were assigned a weight of 0.589, representing the differential consequences of living with the two conditions.

The universal usage of these weights and their failure to account for both qualitative cultural differences and differential access to resources around the world is a cause for concern. For example, it is conceivable to imagine that in developed Western nations, easy access to eyecare professionals has decidedly limited the impact of vision impairment on our daily lives. While the delivery of eyeglasses is a cost-effective intervention, the infrastructure may simply not be present to offer such solutions in developing nations. Similarly, countries with economies highly dependent on manual labour might highly value their physical mobility, and as such be much more negatively impacted should they encounter a disease that affects the use of their limbs.

Some of these issues may be resolved through the use of individual surveys, in which respondents are presented with a pair of people in different health states and asked to decide the healthier of the two – a potentially meaningless question that introduces subjective value judgements from the paired comparisons (similar to the previously mentioned – what we think causes suffering versus what actually does cause suffering is an opinion constantly in flux). Concerns with representativeness and the bias associated with self-response remain with survey responses, and issues also arise from the sparsity of data in certain regions: lack of available data in developed nations where national health statistics are not collected as rigorously lead to high uncertainties in the estimates.

Despite these issues, the Global Burden of Disease and health metrics such as DALYs are still the most promising venue for understanding population health trends at national and global levels and for quantifying and tracking progress in achieving the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) laid out by the United Nations (UN). It thrusts public health into the big data revolution and has fundamentally altered how people view disease burdens. Where once infectious disease ruled, it is now understood that disabilities result in a much greater loss of health: depression and back pain are much more influential in their contribution to health loss than tuberculosis or cancer, respectively. This underscores two things: countries are getting better at dealing with communicable, maternal, and neonatal diseases such as the measles or preterm birth complications, and countries are not as good at dealing with chronic diseases.

There are, as always, political ramifications: whose agenda is ultimately being served? As Laurie Garrett politely writes, the current framework of global health exists through several billion-dollar annual charity programs that fail to establish working local institutions and ultimately exist without built-in methods of assessing their own sustainability. Certain limitations imposed by national policy, as well as simple denial by countries who disagree with their performance ranking, may impede any sort of action to reduce burdens of diseases in that region.

The IHME serves a unique purpose in this sense: being part of a university does not free it from the critical eye of the broader scientific community, but it does free it from the restrictions faced by its political counterpart, the WHO. Moreover, its existence introduces a degree of competition into the field: the monopoly no longer resides solely in Geneva under the purview of WHO. This has caused some disagreements in the past, but in general, has led to improved collaboration and transparency between researchers.

Lastly, let us not forget the ethical implications of using single statistic metrics for evaluating health and for prioritizing resources. One cost of such metrics as the DALY is the loss of narrative: the reduction of all of an individual’s suffering is aggregated at a population level into one number. Another stems from the idea that demands for quantitative data can potentially undermine local knowledge. Lastly, it is important to consider the question of assuming blind neutrality health priority-setting. Chris Murray has stated that the philosophy of metrics like DALYs rests on the principle of equal merit: the death of a woman living in the slums of Bogota should contribute just as much to the estimates of global burden as a wealthy philanthropist in Boston, replacing personal convictions with an “effective altruism” which operates within the realm of mathematical neutrality. Indeed, it is often said in statistical sciences that researchers should “let the numbers speak” without any influence from outside players, but this is easier said than done. Not only are assumptions implicit in all statistical techniques, political outcomes can sometimes outweigh health: nations provide less-than-accurate surveillance data to inflate their progress, yielding questionable results that are not always transparent [2]. This may result in only a small departure from the target calculation, but the impact can be potentially enormous.

While the global health metric monopoly may no longer solely reside in Geneva, a monopoly exists nonetheless: both IHME and WHO are the largest players in the field of global health metrics, existing in a massive money pit that links health to profit generation of public-private partnerships [2]. The metrics the IHME produces are not entirely independent of political outcomes and their production for the GBD study carries enormous political sway for politicians. Yet for this failing, its independent research still informs efforts made by non-political organizations such as the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, which may prove to be a critical player in the future, especially given the United States’ recent decision to downsize the Center for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) global epidemic prevention activities. The best solution at this point is to move forward with transparency and with a clear cognizance of how these metrics are used by the states they serve. Understanding their imperfections, researchers and countries should supplement indicators like the DALYs with local qualitative knowledge for responsible health priority-setting.

[1] Bek-Thomsen, J., Christiansen, C. O., Jacobsen, S. G. and Thorup, M. (2017). History of Economic Rationalities: Economic Reasoning as Knowledge and Practice Authority. 1st ed. Springer International Publishing.

[2] Adams, V. (2016). Metrics: What Counts in Global Health. 1st ed. Duke University Press.

Edited by Marissa Fortune.