The Imperial Imam: Islam, Empire, and the Diplomacy of Revolutionary Iran

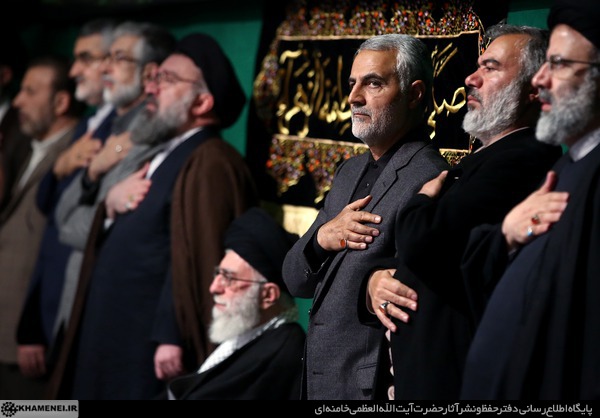

TEHRAN, IRAN - JUNE 04: (----EDITORIAL USE ONLY – MANDATORY CREDIT - IRANIAN SUPREME LEADER PRESS OFFICE / HANDOUT" - NO MARKETING NO ADVERTISING CAMPAIGNS - DISTRIBUTED AS A SERVICE TO CLIENTS----) Supreme Leader of Iran, Ali Khamenei greets the crowd during the ceremony marking the 28th death anniversary of Ruhollah Khomeini, founder of the Islamic Republic of Iran, in Tehran, Iran on June 4, 2017.

( Supreme Leader Press Office / Handout - Anadolu Agency )

TEHRAN, IRAN - JUNE 04: (----EDITORIAL USE ONLY – MANDATORY CREDIT - IRANIAN SUPREME LEADER PRESS OFFICE / HANDOUT" - NO MARKETING NO ADVERTISING CAMPAIGNS - DISTRIBUTED AS A SERVICE TO CLIENTS----) Supreme Leader of Iran, Ali Khamenei greets the crowd during the ceremony marking the 28th death anniversary of Ruhollah Khomeini, founder of the Islamic Republic of Iran, in Tehran, Iran on June 4, 2017.

( Supreme Leader Press Office / Handout - Anadolu Agency )

The foreign policy of the Islamic Republic of Iran has been shaped by its revolutionary, Shia Islamist and imperial Persian origins. The regimes led by Ayatollah Khomeini (1979-1989) and Ali Khamenei (1989-present), the Supreme Leaders of the Islamic Revolution, have been viscerally anti-American, anti-Zionist and anti-Saudi with a proactive interventionist foreign policy agenda in the “Shia crescents” of the Arab World: Iraq, Lebanon, Yemen, Syria, Bahrain and the oil-rich Eastern Province of Saudi Arabia. Since the 1979 Revolution, political opportunism, revolutionary passion, and pan-Shia solidarity have shaped Iranian grand strategy.

Saddam Hussein’s invasion of Iran in September 1980 fundamentally reshaped the religious elite of the regime and spurred it to create new paramilitary institutions to both assure regime survival and project Tehran’s soft power abroad. The classic example is the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC). The Revolutionary Guard has been the military, financial and political patron of Iraq’s Shiite militias, the Lebanese Hezbollah, the Syrian Ba’athist regime and Yemen’s Houthi rebels. Led by the brilliant, if ruthless, Major General Qassem Suleimani, the IRGC answers directly to Supreme Leader Khamenei, not to President Hassan Ruhani or the Majlis (parliament) in accordance with Khomeini’s doctrine of vilayet-e-faqih (the domination of the Supreme Shia jurist).

The financial, industrial and banking empires of the Revolutionary Guards have led to corruption on an epic scale and triggered anti-regime protests in 2009 and 2017. Akin to the Roman Empire’s Praetorian Guard or the Ottoman’s Janissary’s, The IRGC is at the pinnacle of revolutionary Iran’s military-political-legislative industrial complex. The IRGC also triggered Tehran’s decision to intervene in the Syrian Civil War, even if this decision gutted Iran’s relations with Turkey, Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and NATO. Despite the ideological conflict between Ba’athist secularism and Iranian pan-Islamist theocracy, the Assad regime in Damascus has historically maintained close relations with the Ayatollahs of Tehran, dating back to the Iran-Iraq War. The “Great Satan’s” obsessions with Iranian diplomacy are the products of the political insecurities of Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei, a man without Khomeini’s charisma, revolutionary pedigree or Shia theocratic credentials. Khamenei is like Churchill’s Clement Atlee: “a modest man with much to be modest about.” However, he is also a living example of Dr. Henry Kissinger’s great insight: “Even a paranoid has some enemies.”

The constitution of the Islamic Republic mandates the regime to “defend the laws of all Muslims”; the rationale for its aggressively anti-Zionist foreign policy and passionate defense of the Palestinians. Realpolitik has also played a role in Iran’s anti-Zionist, anti-Israeli, and even anti-Semitic stances. The Pahlavi regime was once a staunch ally of Israel, while acting as the champion of the Palestinian cause, enabling Iran to position itself in the central political cause of a predominantly Sunni, Arab regional order. With the fall of the Pahlavi Dynasty, Khomeini’s Islamic Republic severed all ties with Israel and disqualified the Shah’s recognition of the state. Today, Tehran maintains a hostile stance against Israel; currently leading the chorus of Islamic condemnation against Washington’s recognition of Jerusalem as the capital of Israel. Iran’s Ayatollahs did not abandon Iran’s imperial pedigree; resurrecting the Shah’s claims that minority Sunni-led, predominantly-Shiite Bahrain was a province of the ancient Sassanid Empire. Tehran has also not relinquished its occupation of the UAE’s Abu Musa and Great Tunbs islands in the Arabian Gulf (or the Persian Gulf according to the Iranians), an occupation originally ordered by the last Shah in 1971.

Qajar and Pahlavi Iran was often a victim of the Great Game between the British Empire and Tsarist Russia. After the CIA engineered a countercoup against democratically elected Prime Minister Mohammad Mossadegh in 1953, the Iranian regime became a de-facto client state of the United States in the Cold War. This provoked outrage from Iran’s religious elite, notably Ayatollah Khomeini, who was deported to Iraq after riots broke out against the Shah’s decision to grant religious immunity to US citizens living in Iran. As in the 1892 anti-British riots provoked by the Qajar Shah’s tobacco concessions, the Mullahs of Iran embraced the xenophobic and Persian nationalist mythologies of Iranian history to mobilize the masses in anti-regime protests in 1979.

The Islamic Republic adopted a formal policy of non-alightment in the Cold War, since a Shia theocracy could hardly ally with the Marxist-Leninist Brzehnev dictatorship in the Kremlin. This “neither east nor west” foreign policy and the trauma of the Iran-Iraq War enabled the Ayatollah and IRGC to create the political and logistical infrastructure that eventually led to the creation of pro-Iran Shia militias in Iraq, Lebanon, and Afghanistan.

Iran is an “ideological state” since its Constitution mandates its armed forces to protect not only its frontiers but to wage ‘jihad in God’s way’ by expending the ‘sovereignty of God’s law throughout the world.’ The Islamic Revolution’s onset coincided with a merciless civil war against remnants of the Shah’s regime, the leftist Mujahadeen-e-Khalq, ethnic Kurds and Baluch revolts, and the virtual extermination of Iran’s Communist Party. Khomeini often urged his followers to “export” the Islamic Revolution across the world. In fact, it was precisely these revolutionary exhortations to the Shias of Iraq that motivated Saddam Hussein to invade Iran in September 1980 in an abortive attempt to overthrow the Khomeini regime.

The Ba’athist invasion, ironically, enabled Khomeini to consolidate his power, eliminate his secular opponents and establish the world’s first Shiite theocratic regime. The regime used the Shia historic memory of martyrdom and Arab Sunni oppression to wage war against Iraq. Religious zealousness mobilized Iran’s youth to act as human minesweepers and suicide bombers in the battlefields of the Shatt-al-Arab and Khorramshahr [1]. The horrific human toll of the Iran-Iraq war still legitimizes the regime’s struggle against Western imperialism and its Sunni Arab monarchial enemies.

However, theology and fanatical infighting often trumped international political logic in Iranian diplomacy. By 1988, UK-Iran bilateral relations began to normalize, with the re-opening of the British Embassy in Tehran. However, Khomeini’s 1989 fatwa against Salman Rushdie, for his ‘blasphemous’ novel The Satanic Verses, doomed a post-Iraq war diplomatic and economic rapprochement with Britain. President Mohammad Khatami’s attempt to improve relations with Saudi Arabia was derailed by the Al Khohar bombings and violent demonstrations during the Hajj pilgrimage in Makkah. In 2013, President Ahmadinejad triggered the Guardian Council after proclaiming that the “innocent spirit” of the deceased Venezuelan President Hugo Chavez will return “with Jesus Christ” to “help humankind establish peace, justice, and kindness.” As one can tell, the theocratic and Republican faces of Iran don’t see eye-to-eye.

Iran’s foreign policy also exploited opportunities created by regional wars and uprisings. In 1985, Iran’s IRGC established Hezbollah after the 1982 Israeli invasion of Lebanon and expelled the PLO, the main political rivals of the Lebanese Shia. In September 2001, Iranian intelligence helped US Special Forces attack and vanquish the Taliban regime of Mullah Omar, another regional rival for Tehran. In 2003, Iran used Iraqi Shia militias to establish its influence in post-Baathist Iraq after George W. Bush helpfully overthrew the regime’s arch-foe Saddam Hussein. Iranian intelligence also established subversive networks among the Shia communities in Kuwait, Bahrain, and the Saudi Eastern Province.

It is no coincidence that Iran became the most successful proponent and sponsor of proxy warfare and insurgency in the Middle East. Hezbollah, for instance, rained (Iranian manufactured) missiles on Israel’s Galilee kibbutzim during the 2006 Lebanon War and created a balance of terror on the border of the Jewish State. Hezbollah also operates Iran’s arms supply networks in the Levant, and its fighters played a crucial role in the Assad regime’s victory over its myriad enemies in the Syrian civil war. Iran’s Shia milita proxies also enabled the election of both Prime Ministers Nuri Maliki and Haider Ahadi in Iraq. Iran has used its anti-Israeli policies to advance its claim to regional leadership against its Sunni rival Saudi Arabia, ruled by a royal family historically allied to Britain and the United States. The regime’s pan-Islamic rhetoric camouflages a sectarian Shia agenda in Iraq, the Gulf States, and Lebanon. Xenophobia, regime survival, imperial angst, sectarian Shia zeal and international isolation make revolutionary Iran both erratic in its foreign policy and prone to conflict escalation with its regional, foreign, and sectarian rivals.

Edited by Benjamin Aloi

Biblography

[1] Pollack, Kenneth M. (2004). “Iraq”. Arabs at War: Military Effectiveness, 1948–1991. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.