Is Jakarta Running Ahok? The Resurgence of Ethno-Religious Intolerance in Indonesia

At a press conference on 2 November 2016, FPI party officials declare Ahok should arrested and detained for blasphemy. https://flic.kr/p/P8JuuL

At a press conference on 2 November 2016, FPI party officials declare Ahok should arrested and detained for blasphemy. https://flic.kr/p/P8JuuL

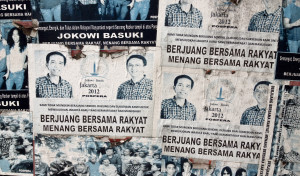

Governors’ posts in seven provinces, mayors’ and regents’ in 18 cities, as well as local leaders in 76 districts were at stake in Indonesia’s regional elections on 15 February 2017. However, the contentious race for the Jakarta governorship has overshadowed the rest of the elections, as fake news and manifestations of religious intolerance have surrounded the candidacy of Basuki Tjahaja Purnama. Also known as Ahok, the incumbent governor since 2014 is only the second non-Muslim public official in this post since independence, and represents the Indonesian Democratic Party of Struggle (PDI-P). He fell short of an absolute majority on Wednesday by winning 43% of the vote. His main opponent, Anies Badeswan of the Great Indonesia Movement Party (Gerindra), managed to secure 40% of the vote. The son of former President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono, Agus Harimurti Yudhoyono of the Democratic Party (PD), abandoned the race after garnering only 17% of the votes. The close scores of the three-way race call for a second electoral round to the capital’s governorship to take place on 19 April 2017. In order to understand the tensions surrounding this election, it is paramount to consider Ahok’s ethnicity and religion: as an ethnic Chinese and a Christian, the incumbent governor is at the intersection of two minority identities that have historically been discriminated against in Indonesia, and more particularly so in the Indonesian political sphere. Winning Jakarta’s public opinion would have been challenging enough for the 2017 elections, but Ahok must now win in the courts as well as in the ballots to remain in power, as a blasphemy trial is currently investigating claims of an alleged defamation of Islam in September 2016. To this day, there is only one registered case of a defendant’s victory in a blasphemy trial in Indonesia. Prospects are dim – both for Ahok and for Indonesia’s fledgling liberal democracy.

Blasphemy, Fake News, and Violent Mass Protests

Traditional strongholds of liberal democracy in the West are not the only contexts in which we see phenomena such as mass disinformation through fake news, ethno-religious polarization, and violent manifestations of political angst emerge around election time. Indonesia, in spite of being conventionally hailed as a symbol of democracy and religious pluralism in Southeast Asia, is in fact not immune to these trends. For Election Day on February 15, the Jakarta police had planned to deploy 16,000 officers, as concerns remained about the fringe Islamist groups’ organization of violent anti-Ahok protests similar to those that unfolded in November 2016.

In September 2016, Ahok’s mention of the Al-Maidah 51 Koranic verse – which allegedly bars Muslims from voting for a non-Muslim political candidate – in a speech to a community of fishermen was used as grounds for accusations of denigration and blasphemy by Islamist organizations. These then proceeded to foment sectarian outrage through the manufacture and diffusion of an edited video of Ahok’s speech, the diffusion of dubious reports claiming Mr. Basuki was “a puppet of Beijing”, the promotion of the use of ethnic and religious slurs, as well as the staging of mass protests advocating the imprisonment and lynching of the governor. Rizieq Shihab, leader of the vigilante group Islamic Defenders Front (FPI), has actively worked against “Ahok the blasphemer,” publicly denouncing him as an “infidel” in mosques and rallies. Some 500,000 people were drawn to the protests at the highest point of the anti-Ahok campaign in early December, although more moderate religious leaders such as the secretary general of Nahdlatul Ulama, Yayha Cholil Staquf, discouraged followers to take part in the events. The blasphemy trial began on 13 December 2016, and Ahok declared he was “devastated of being thus accused of insulting Islam, as it would mean [he] had slandered Muslims, a [religious] family [he] loves”. Despite his attendance at court, Ahok has maintained his campaigning efforts, with some relative success.

The Resurgence of Ethnic and Religious Intolerance in Post-Suharto Indonesia

The two months between the electoral ballots for Jakarta’s governorate (an administrative unit similar to a state or province) will reveal more about the state of democracy and religious tolerance in Indonesia. Indeed, this election has been hailed by the international community as a test for Indonesian society, which rests on the precarious pillars of godly nationalism, the stability of which is increasingly threatened by mounting claims for stronger state intervention in the delimitation and enforcement of religious orthodoxy. The tensions surrounding the election of the Jakarta governor are therefore not isolated from broader trends in Indonesian politics. In fact, they can be clearly seen in continuity with the mounting pressure applied by fringe Islamist organizations on the state since the fall of the New Order, a pressure which pushes towards the ultimate aim of an Islamic state as set forth in the (rejected )1945 Jakarta Charter.

Indonesia is neither particularly religious – as it is not an Islamic state – nor secular – as the state engages in the delimitation, production, and reproduction of a godly nation. Three institutions are central to the establishment and continuity of Indonesian godly nationalism. The Pancasila’s first principle constitutionally enshrines “belief in one God” at the center of the Indonesian state and nation. Further, the Departemen Agama (Department of Religion) upholds a narrow definition of religion as including only those traditions that are “monotheistic […] with belief in the existence of One Supreme God, a holy book, a prophet, and a way of life for its adherents” in recognizing six state-religions – Islam, Catholicism, Protestantism, Hinduism, Buddhism, and Confucianism. Although the latter three traditions seem to run counter to the above definition, the first Pancasila principle grants different interpretative spaces to each of the six traditions in order to accommodate territorially-concentrated ethnic minorities of these traditions – most Balinese are Hindu, and most ethnic Chinese Indonesians are Buddhist. Finally, the 1965 Blasphemy Law guarantees the state and the courts’ uncontested prerogatives in setting the boundaries of religious orthodoxy and deviance.

The fact that Ahok has been brought to court precisely under the 1965 Blasphemy Law is not to be overlooked. It is yet another instance in which the Indonesian state shows the depth of its discriminative intervention in the private lives of its citizens. It is interesting to analyze the specific discourse in which Ahok’s trial is embedded. If a similar situation had taken place in France, the public figure would have been mostly accused of ‘sectarianism’ in making reference to religious scriptures in the public sphere; in Indonesia however, it is rather the fact that Ahok, as a private individual as well as a public official, would have made an allegedly wrongful reference to religious scriptures that has caused such controversy. This shows the significant extent to which the Indonesian state delimits orthodoxy and deviance through normative and legal discourses affecting the public and – most importantly – the private spheres in which citizens evolve. As a consequence, religious relations have significantly degraded since the fall of Suharto; stronger emphasis on religious orthodoxy was embraced by the central state as a means to maintain an ethnically and religiously fractionalized archipelago under a single political roof. Religious intolerance has risen accordingly against those individuals and groups who do not fall neatly within the six categories defined by the state, as showcased most strikingly in the mounting violence against the Ahmadiyah Muslim minority sect and, to a lesser extent, against religious minority groups such as Jews and Sikhs.

Also, the idea that, as an ethnic Chinese in one of the highest positions of power in the country, Ahok might further shift positions of political power away from the traditionally political Indonesian elite, and towards the traditionally economic ethnic Chinese elite, has been perceived as a sizable threat by Jakarta’s elites. The rise of Chinese elites in the political sphere is indeed perceived as a threat by Indonesian elites. Although they represent only slightly more than 1% of the Indonesian population, Chinese-Indonesians have risen to a place of considerable economic clout over time. This has been the source of bitter resentment on the part of Indonesians – as showcased in the bloody history of ethnic riots of the country. Further, the ethnic Chinese’s gains in the political sphere since the 1999 democratic transition and the implementation of direct democracy at all levels of government have certainly not improved ethno-religious and minority-majority relations, as political office has long been seen as the preserve of the majority.

Dim Prospects

As the race now explicitly pits Christian against Muslim, and ethnic Chinese against Javanese, the tensions of post-Suharto secessionist conflicts of the 2000s seem to resurge with “extreme acrimony” in the social tensions polarizing the nation. And the candidates in the race know this all too well. Ahok’s opponent, Anies, has unequivocally shown his intent of capitalizing on the conservative Muslim vote of the southern and eastern areas of Jakarta, as shown in his recent decision to favour Islamic dress, visit Islamic educational institutions and civil society organisations, and most significantly, his increasing involvement in the anti-Ahok rallies organized by Shihab.

For those who choose to mobilize along ethno-religious polarization lines as a short-term electoral strategy to maximize votes, Islamist discourse is only a platform to bolster their position in the race for political office. For Muslim minorities such as the Shiites and the Ahmadis, as well as for other religious minorities who are excluded from the state’s delimitation of religious orthodoxy in godly nationalism, the consequences of these electoral strategies will be deeply felt, and will only provide further power to political visions that threaten their very existence and persistence in Indonesian society.

There are sombre dynamics at play in the race to the Jakarta governorship, and these dynamics are more than likely to gain prevalence in the 2019 presidential elections. Until moderate Islamic organizations such as Muhammadiyah and the NU engage with the issue further, no one in civil society will dare to oppose a vocal though dangerous radicalizing minority.