LGE 2016: Uncertainty Reigns as South Africa Enters New Political Era

August 3rd was the day of the 2016 local government elections (LGE) in South Africa, marking a turning point in history. With support for the African National Congress (ANC) falling a staggering 8 percentage points from the 2011 elections to just 53.9% of the popular vote, its lowest level ever, the opposition Democratic Alliance (DA) now appears poised to seriously challenge the party of Mandela in the 2019 national race. However, far more questions remain, and in a country ravaged by socioeconomic divisions and government corruption, not to mention rampant unemployment and poverty, political uncertainty reigns.

There are a number of angles from which to analyse the results of LGE 2016, and explanations of the ANC’s collapse run the gamut from internal party divisions to the country’s shifting demographics. The pro-Zuma wing of the ANC has largely hedged its electoral prospects on heavy-handed rhetoric, forcibly reasserting the party’s liberation history and struggle credentials even in the face of unprecedented corruption, whilst simultaneously vilifying internal dissidents and opposition parties. It has repeatedly accused the Democratic Alliance (DA), a party rooted in the liberal democratic tradition of the Progressive Party (PP) that has governed the Western Cape province since 2009, of “upholding white supremacy.”

A decade ago, the ANC might have had a legitimate case in making this claim, as the broadly centrist DA initially struggled to connect with black voters beyond its relatively affluent and disproportionately white and Coloured (mixed-race) electoral base in the Cape. The DA’s economic emphasis on building strong public-private partnerships and attracting foreign investment to South Africa has not always met sympathetic ears in an overwhelmingly poor, unemployed nation with a deep history of African labour exploitation. Indeed, much of the ANC’s traditional support, both during the anti-apartheid struggle and after assuming political power, comes from influential trade unions such as the National Union of Mineworks (NUM) and the other 20 affiliates of the ANC’s coalition ally, the Congress of South African Trade Unions (COSATU). The legitimacy of this alliance, however, has rapidly deteriorated under the Zuma administration, and the 2012 Marikana massacre galvanised thousands of unionised workers against not only government police forces, but also the NUM and COSATU leadership. Zuma, for his part, in addition to maintaining a cronyistic relationship with the powerful Gupta business family, has effectively used state coffers as a personal bank account, hijacking US $23 million in public funds for upgrades to his private palace in rural Kwazulu-Natal. In a March 2016 decision, the South African Constitutional Court unanimously ruled that Zuma’s upgrades violated the country’s constitution and ordered the National Treasury to determine the exact amount he must repay. Despite numerous calls for his resignation from both major opposition parties as well as prominent voices within the ANC (including Ahmed Kathrada, Ronnie Kasrils and Trevor Manuel), a DA-led impeachment vote in the National Assembly was resoundingly defeated.

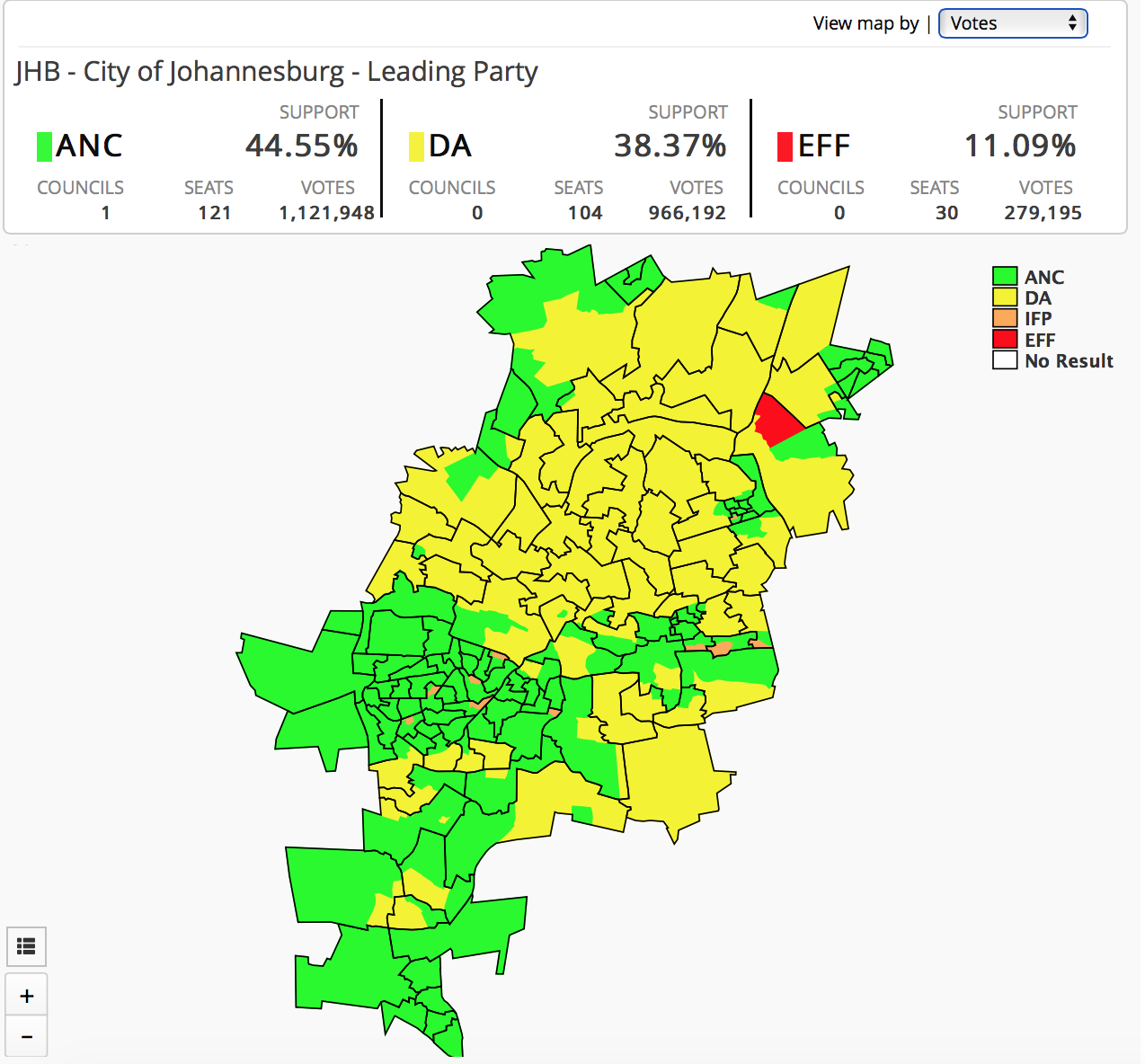

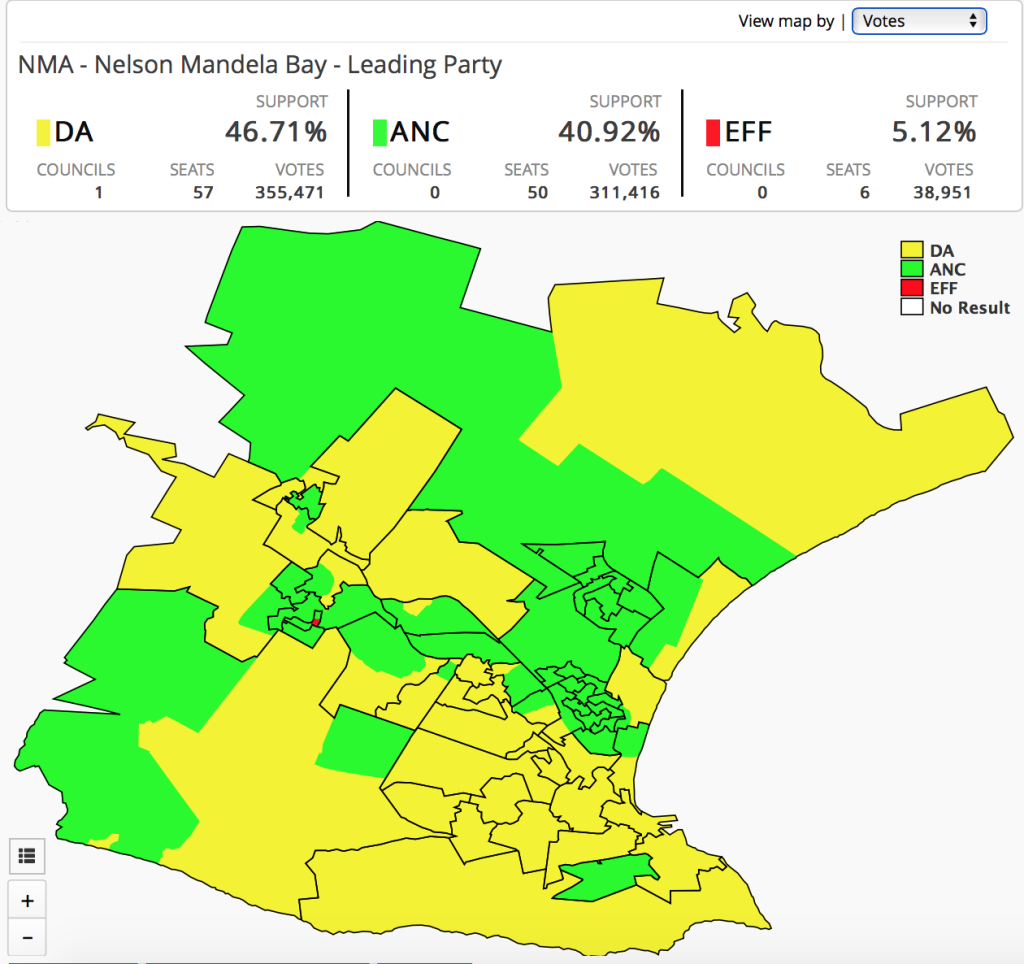

Nevertheless, the ANC has now paid dearly for its transgressions at the ballot box. Nearly 10 years of government corruption and stalled delivery of essential social services has alienated urban workers across Gauteng province, to say nothing of the ANC’s massive electoral losses in Nelson Mandela Bay (home to Port Elizabeth) and rural Limpopo province, now a stronghold of the revolutionary socialist Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF). The three year-old EFF, led by former ANC Youth League leader Julius Malema, has tapped into the frustration and disillusionment of young South Africans (63% of the total labour force aged 15-24 is unemployed) to usurp a sizeable portion of the ANC’s urban support in the span of a single election cycle.

Meanwhile, the DA diversified its campaign in this election, crafting a modern party brand and building its institutional capacity across South Africa. Its message—somewhat miraculously—resonated most strongly in cities. Johannesburg, Tshwane (Pretoria and surrounding towns) and Nelson Mandela Bay (Port Elizabeth and surrounding towns) were easily the three principal theatres of LGE 2016, and in all three metropolitan municipalities, the DA vastly outperformed expectations.

Mmusi Maimane, the first black leader in the party’s history, ran on a campaign of effective and transparent service delivery, recognising the vital significance of rationally restructuring municipal governance in the march towards a more responsive national bureaucracy. Rather than exacerbating racial divisions, “momentum building going towards 2019 [the year of the next national elections] is about good governance,” Maimane insisted.

“The most historic thing about this election is people rejected the racial divisions and said it’s possible for black and white South Africans to work together…In 1994, the choice was between freedom or apartheid. The ANC has always sought since then to make the choice about black or white. But the ANC misread South Africa.”-Mmusi Maimane

Ultimately, the outlook for South Africa’s political landscape is a mixed bag. On the one hand, the proliferation, in less than a decade, of not one but two viable opposition parties to the African National Congress (ANC) is a testament to the strength of the country’s democratic institutions. As The Guardian’s Justice Malala quite astutely points out, LGE 2016 represents a welcome departure from the African “post-colonial narrative” of former liberation parties maintaining a stranglehold on political power long after their governmental competence has expired. One can observe this disturbing phenomenon in countless countries across post-colonial Africa, and there is perhaps no better example than Rogert Mugabe’s 36-year reign in Zimbabwe, immediately to the north of South Africa.

Among many other leadership traits, what made Nelson Mandela exceptional was his ability to recognise that his country’s long-term prosperity and political stability were far more important than the romantic narrative of his own liberation, or the narrative of the entire ANC, for that matter. In voluntarily stepping down after one presidential term, an affront to Mugabe and other self-serving dictators across the African continent, Mandela laid the foundations of the vibrant political pluralism we see in South Africa today. Malala is thus absolutely right to laud LGE 2016 as the “maturation of our politics and the steady, welcome move towards a lively, competitive, responsive multi-party democracy.”

On the other hand, there is no guarantee that South Africa’s current strain of multi-party democracy will necessarily lead to more progressive ends. Rather than acknowledge its shortcomings and adopt a more constructive campaign message, Zuma and the ANC doubled down on their race-based criticisms of the DA, describing the party as “snakes, the children of the National Party,” and Maimane himself as a “puppet of whites.” Not only have these personal attacks tarnished the ANC brand, but they also prominently display Zuma’s increasing detachment from reality, as urban blacks in Johannesburg, Pretoria and Port Elizabeth—not just affluent Cape whites—turn out in millions to vote for the DA. It is encouraging that the ANC have faced electoral consequences for their failures, but they still control roughly 62% of National Assembly seats and, thanks to the party’s continued dominance in rural areas, 161 of 213 council municipalities. An endemically corrupt ANC is bad for the entire country, and service delivery systems will continue to suffer unless the party undergoes a thorough transformation.

Moreover, there is the inescapable uncertainty that comes with a divided government. After the final election results were tallied over the past weekend, 27 hung municipalities (where no party manages to claim a majority of the vote) remained nationwide, including 4 of the country’s 8 metropolitan municipalities.1 It is certainly possible that the DA or ANC, who have shown little interest in forming a coalition despite the fact they have far more common ideological ground with one another than with the EFF, could try to form minority governments in the municipalities where they won a plurality of votes. However, what is far more likely is a haphazard municipality-by-municipality process of negotiations wherein minor parties like the EFF, Inkatha Freedom Party (IFP) and the Congress of the People play kingmaker in any potential coalition.

This presents several challenges. First, while the ANC may be willing to compromise at the local level in order to salvage the most political power possible in municipalities where their popular support is steadily waning, “broader policy changes might be difficult if these are in conflict with the ANC’s own policy positions. Only ANC national conferences can decide and determine policy, and therefore the powers of the ANC negotiators would be limited on demands such as nationalisation and property ownership.” All initial signs point to this latter scenario occurring, as nearly every opposition party with government representation has called for Zuma’s immediate removal from the presidency, among other major shakeups at the national level.

Moreover, to return to an earlier point, a bitterly divided and dysfunctional ANC spells disaster for the entire political system. There is a real sense among the Gauteng ANC that the national party leadership cost them countless votes in this election by uncritically promoting Zuma’s image and policies in the face of staggering public resentment across the heavily-urbanised province. South African society is changing in ways that will be not be kind to the ANC’s divisive approach, and the Gauteng ANC is understandably trying to distance themselves from national party policies as much as possible. As The Daily Maverick’s Stephen Grootes wrote shortly after the final election results poured in from Johannesburg,

“In 2014, the Gauteng ANC fought a huge fight to be allowed to appoint its own choice as Premier. Zuma, and the national ANC, wanted Ntombi Mekgwe. In what became a significant victory, the provincial party was able to force the appointment of its own deputy chair, David Makhura. This was the start of a new experiment in our politics. Makhura, and his administration, were well aware that defeat in 2019 was staring them in the face. If you have won just 53.5% of the vote, you tend to start planning for the future. Their strategy was to try a simple strategy: govern better, be more open, crack down on corruption, and, as far as possible, try to differentiate yourselves from the national ANC.

It was an experiment that met with success. Makhura and his government are generally seen as clean, effective, and efficient. There were some clever initiatives as well: Makhura set up a Social Cohesion panel, and appointed people with legitimacy from all different groups in the province. He knew that if he could get ahead of the national discussion on race, he could again pick up votes from coloured and white voters.

This was the first time that the ANC was trying to win back votes, simply through better governance.”

Unfortunately, Zuma loyalists have not taken kindly to this increased autonomy for the ANC’s most powerful provincial chapter, and following last week’s electoral debacle in Gauteng, all indications point to a complete overhaul of municipal leadership in both Johannesburg and Tshwane. Widely-respected Johannesburg mayor Parks Tau will now likely find himself out of a job, as will numerous other policymakers in the his administration who have worked tirelessly to expand public transportation, implement environmental sustainability initiatives, diversify the city economy, incentivize investment in the CBD, promote neighbourhood-based service delivery, tackle corruption, and ensure citywide access to HIV/AIDS treatment.

Finally, a scenario in which either the EFF or IFP (or both) assume a significant level of government influence, such as double-digit proportional representation in the National Assembly, is a major cause for concern. An extremely socially conservative party with a brutal history of political violence against the ANC, the IFP continues to mount a formidable electoral challenge in local municipalities across Kwazulu-Natal, winning 7 in the province on Thursday (including President Zuma’s home district of Nkandla). A governing coalition dependent on IFP support would see a massive devolution of powers to traditional African communities and their leaders, at the expense of millions of impoverished South Africans desperately in need of comprehensive service delivery systems at the municipal, provincial, and national level.

Meanwhile, the EFF have displayed a disturbing level of misogyny, xenophobia and hostility in their inflammatory rhetoric. Malema himself has twice been convicted of hate speech, the former for claiming the woman who accused Zuma of raping her in 2005 “had a nice time” (before his 2012 expulsion, Malema was a loyal member of the ANC who campaigned particularly hard for Zuma’s 2007 bid for the party presidency) and the latter for inciting public violence against Afrikaners. Furthermore, he has single-handedly dictated the party’s official stances, mostly vague denunciations of capitalism and international finance, in such a carefully-controlled fashion as to manufacture a personality cult around his own red jumpsuit-clad image. This is not to suggest that South Africans’ concerns about structural economic inequality and instability, concerns which the EFF deftly tap into, are illegitimate. They absolutely are, and they are essential for the ANC to understand if they are to have any hope of regaining their former stature.

As the Cameroonian postcolonial theorist Achille Mbembe writes, “it might be that [the EFF] has no real principles of its own and simply dresses itself in the ideological costume it thinks will be most attractive to the masses.” Nonetheless, the ANC and DA both must recognise the radical party’s rise as a “dramatic manifestation of the structural incompleteness of South Africa’s democracy,” rather than dismiss it wholesale if they are to have any hope of translating EFF supporters’ legitimate grievances into actionable political solutions. This manifestation may remind South African voters that, “political equality without property is not only fragile, but also fictitious.” In other words, the movement’s concerns must be detached from the toxic conditions—a militant revolutionary group led by a champagne socialist with a penchant for inflammatory rhetoric—under which they found a voice.

These are the turbulent waters all parties and voters will attempt to navigate over the course of the next three years, as South Africa builds to the most genuinely competitive national election in its history. For the first time in over 20 years, the ANC finds itself in the daunting position of having to defend its right to lead the country it helped liberate. What is much more concerning, though, is the question of who—if anyone—will step up to fulfill the promises of non-racial democracy, a question to which the answer remains woefully unclear.

1 In South Africa, there are 52 districts. 8 of these districts are large urban areas (Johannesburg, Pretoria, the East Rand, Durban, East London, Port Elizabeth, Cape Town and Bloemfontein), each of which is governed by a consolidated metropolitan government to handle all municipal affairs. Together, these 8 metropolitan municipalities account for about 40% of South Africa’s total population. The other 44 districts are mostly rural areas broken up into (usually 4-6) local council municipalities.