Meet Japan’s NDP

The conclusive victory of Japan’s Prime Minister Shinzō Abe in last October’s general election was supposed to re-establish his control over Japanese politics and allow him to claim a mandate from the people. Despite a summer marked by scandal, his path to revising Japan’s Constitution for the first time since the war, overseeing the 2020 Olympics, and becoming the country’s longest-serving leader was supposed to have been re-established.

The opposite has happened. The PM was forced to withdraw his labour reform bill once it was found that the Labour Ministry had systematically tampered with data. Long-simmering allegations that Abe intervened to give friends preferential treatment were brought back to the fore due to new revelations, with his categorical denials increasingly ringing hollow, while the Finance and Defence Ministries separately confront serious accusations of cover-up. A senior bureaucrat and a prefectural governor successively resigned due to sexual harassment revelations, leading the opposition to boycott parliamentary sessions (demanding proper repercussions) and forcing the notoriously male-dominated political world to confront #MeToo.

As he loses all control over the political agenda, Abe has fallen in the “preferred Prime Minister” rankings – but the politicians in the race to replace him are all intra-party rivals; there seems to be no serious threat from other parties. Indeed, some speculate that Abe may be planning another snap election, just seven months after the last one, to re-establish his authority, as no opposition group is in a position to defeat his conservative Liberal Democratic Party (LDP).

This is probably a safe assumption for now, but may not be for long, for the upstart recently-formed Constitutional Democratic Party (CDP), now Official Opposition, is now in the slow process of laying out a nationwide infrastructure and policy platform. Whether its ideas and strategies can resonate among the public will be the defining question of Japanese party politics in the coming decade.

An Election Upset

Abe called a snap election last October, expecting to demolish the only significant party of opposition, the feeble and incoherent Democratic Party. Yet, the entry of Tokyo governor Yuriko Koike into national politics, with her creation of the “reform conservative” Party of Hope, shook up the landscape: most Democrats, realizing the dire state of their party, ran under the Hope banner at their leader’s behest – but Koike refused to accept those Democratic MPs who prefer maintaining the Constitution’s Article 9, which renounces the ability to conduct war.

As a result, one week after Koike’s move, liberal Yukio Edano announced the creation of the CDP. Edano is one of the very few Democrats who saw his reputation strengthened over the party’s brief and disastrous stint in power, from 2009 to 2012. As Chief Cabinet Secretary (one of the most powerful positions, resembling a combination of press secretary and chief of staff), Edano became the face of the government response to the earthquake, tsunami, and nuclear meltdown of March 2011. As he appeared before the press every few hours, night and day, in a trademark blue jumpsuit, to calmly and patiently detail the latest facts on the ground, he earned a reputation as a workhorse. “Get some sleep, Edano” trended on Twitter.

Another hashtag – “Run, Edano, run” – helped push him to start up the CDP, rather than let the two conservative parties battle it out one-on-one. As the Party of Hope fumbled – it released a poorly thought-out policy platform that included promises to abolish seasonal allergies and crowded trains, while Koike refused to personally be the PM candidate – momentum went to the CDP, fighting under the banner of “a decent way of politics.” Its Twitter following rapidly overtook that of the LDP (something previous opposition parties had not managed), while polls consistently showed it gaining on its fifteen initial MPs. Its image as a plucky insurgent underdog was strengthened when its final rally was met with a rainstorm, but supporters filled the station plaza anyway.

As ballots were counted the next day, the CDP had overtaken the Party of Hope and ended up with 55 MPs; the party that was supposed to represent only a faction of the former Democrats ended up with more votes than the Democrats altogether. In the aftermath, polls showed the Party of Hope fizzling away, while the CDP’s support held steady. The battle lines for Japan’s political future had been set.

Political Competition in Japan

That the CDP is a “liberal” party requires more explanation than at first glance. In Japan, the labels “liberal” and “conservative” are ubiquitous and binary, but describe different orientations than in the West: conservatives are distinguished by a hawkish stance on security, a desire to amend Article 9, and in many cases a revisionist view on Japan’s wartime past. Conversely, the label indicates very little about policies on taxing and spending, and the “conservative” LDP has been responsible for maintaining and expanding Japan’s infrastructure and welfare state. (More broadly, Japan’s conservatism is much more similar to historical British Toryism, with its ethos of “God, King, and Country”, than to Canada’s free-enterprise conservatism.) “Liberals”, meanwhile, hold dovish views on defence and prefer individualism over Japan’s traditional collectivism.

The division does not cleanly map on to the government-opposition divide, however: some factions of the LDP, as well as its coalition partner, are less hawkish than its leadership, while plenty of conservatives sit in opposition, excluded from the LDP due to issues of policy or personnel. This presents a dilemma for any party seeking to take down the LDP: does it become a second “conservative” party that contests the LDP’s record and proposals but stays away from divisive and immutable questions of ideology? Or does it retain a distinct liberal identity, offering a meaningfully different choice to the LDP, at the cost of a potentially smaller vote base?

Through its two decades of existence, the Democrats have tried to have it both ways, building a heterogenous big tent for anyone opposing the LDP – but October’s election saw the two camps split cleanly. Koike is conservative, in that she is in favour of revising Article 9, even as she called for greater economic intervention; that she offered a primarily cosmetic change to the LDP and its personnel was a source of either comfort or criticism, depending on the perspective. The CDP, meanwhile, was less afraid to call for a newer, more just society, and stridently opposed amending Article 9.

At first glance, this may seem like a foreign and bewildering set of labels – but likely not for supporters of the New Democratic Party (NDP) in Canada, who have long alleged that Liberals and Conservatives are “tweedledee and tweedledum”, with differences in spending masking continuity in such areas as defence and security policy. The CDP also bears similarities to the NDP in that it emerged as an ideologically-cohesive alternative to two catch-all parties, and that it currently occupies one of three poles in party politics, though it aspires to greater heights.

Momentum?

The CDP refuses to label itself as “left” or “right”; instead, it claims that these terms are outdated, and that the most important dividing line in politics is now grassroots vs. top-down. (In this sense, it resembles the Green Party of Canada more than the NDP.) Despite this, the brief document of “Fundamental Principles” that it released in December is essentially that of a standard centre-left party: its ideas include defending freedom of the press and transparency and promising to overturn some of Abe’s more authoritarian legislation; banning corporate donations; more progressive taxation; cutting university tuition; phasing out fossil fuels (particularly coal) in favour of renewables; introducing gender quotas to politics; defending and celebrating the LGBT community.

To be clear, the Democrats were also capable of talking up a progressive game – as described earlier, left-of-centre domestic policy can be compatible with a “conservative” ideology – but translating principles into concrete proposals proved much harder on party unity. With their first policymaking effort, however, the CDP has succeeded where the Democrats failed; it agreed on a proposal to scrap nuclear power entirely and to target 40% renewable energy by 2030 (up from 15% currently). Japan’s nuclear plants, all halted after the Fukushima disaster of 2011, are gradually being restarted under Abe, despite the opposition of a clear majority of the public. Given that the issue is one of the few where most citizens have clear opinions, and in a way that doesn’t cleanly map onto the liberal-conservative divide, the CDP’s bet seems to be that emphasizing nuclear energy would help them draw in voters beyond their committed base.

The CDP is also laying organizational groundwork, setting up prefectural chapters and building a presence in local assemblies. Recent local ballots suggest that the party is still limited in the number of candidates it can recruit, although those that they do perform well. In keeping with its grassroots ethos, the party recently launched a membership program, whose members are invited to join policy workshops; meanwhile, turnout at two recent impromptu rallies in Tokyo has been solid, suggesting that their election result was more than a flash in the pan.

What Happens Now?

As mentioned, the Democrats’ playbook was to combine lawmakers from all political stripes, from nationalist to social-democratic, under a single tent and present a “united front” to the LDP. Japan uses single-member districts, which tends to lead to a two-party system. Therefore, there must be only one non-LDP party, little matter what it stands for. However, one can reasonably imagine that people are less likely to go out and vote for an amorphous blob of a party whose constantly squabbling factions can’t agree on policy – and the demise of the Democratic Party seems to be evidence for this.

Yet, Democratic logic lives on: just this month, the empty shells of the Democrats and the Party of Hope merged under the banner of the “Democratic Party for the People”, and invited the CDP to join them, to reconstruct their united front. The CDP has refused, claiming not to be interested in mindlessly “adding numbers together” in Parliament.

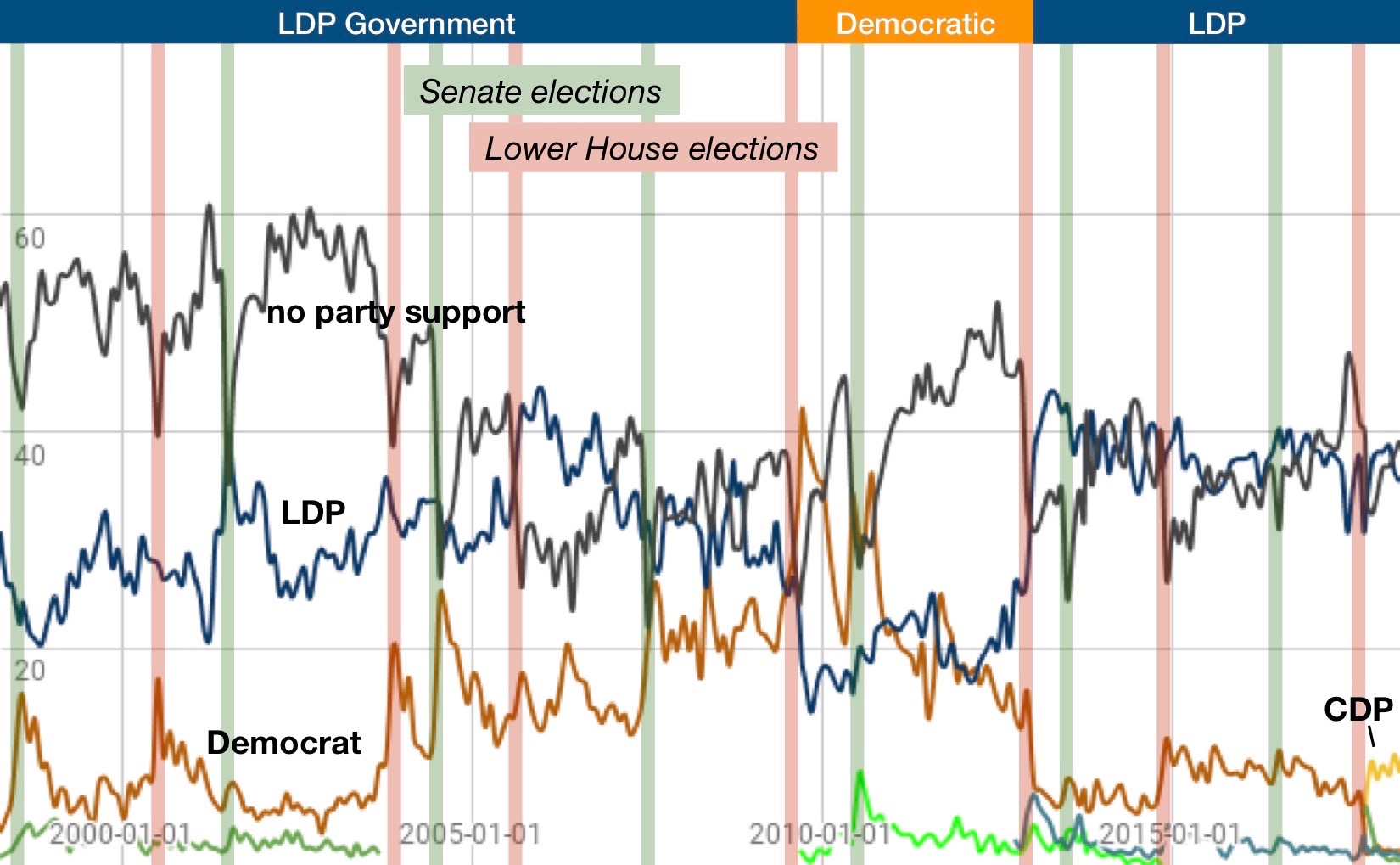

And why wouldn’t it refuse? In terms of polling, the CDP is leaving the other opposition parties in the dust. This past month’s polls saw an average of 10% of respondents self-identify with the CDP, while Hope and Democrats take 1-2% each; meanwhile, the LDP are at 35%, and a full 40% identify with no party at all. (Japanese polls measure party ID, with an option for “no party supported”, rather than voting intention like in Canada.)

Polling since the turn of the century suggests that opposition parties often dramatically gain support during national election campaigns, but stagnate in between (see above graph). Shifts in support for the governing party are usually offset by shifts in “no party supported”, while the opposition stays steady. For this reason, there seems to be literally no way to predict how the CDP (or the new People’s Democrats) will perform in future national elections – a significant proportion of citizens will withhold judgment until they hear each party’s electoral appeal directly.

This is where the possibility of a snap election re-enters the picture. For the moment, all opposition parties have refrained from demanding that Abe dissolve parliament and go to the people, perhaps believing they would be doomed in an actual election. But for the CDP, this may very well be untrue. It is hard to imagine the party losing votes compared to last fall – it has the same leader and outlook, is better organized, and faces a less popular incumbent – while history suggests they might see a spike in support during the campaign. It might, in short, be an extremely clarifying election, one that puts to the test whether a liberal party could do well in Japan, and one that may put to rest the notion (personified by the People’s Democrats) that lumping together disparate parties is a winning strategy.

Bring it on, Abe.

Edited by Benjamin Aloi