Nicaragua: No More Time for Pitiful Updates

"A woman stands near a burning barricade holding the national flag of Nicaragua."

"A woman stands near a burning barricade holding the national flag of Nicaragua."

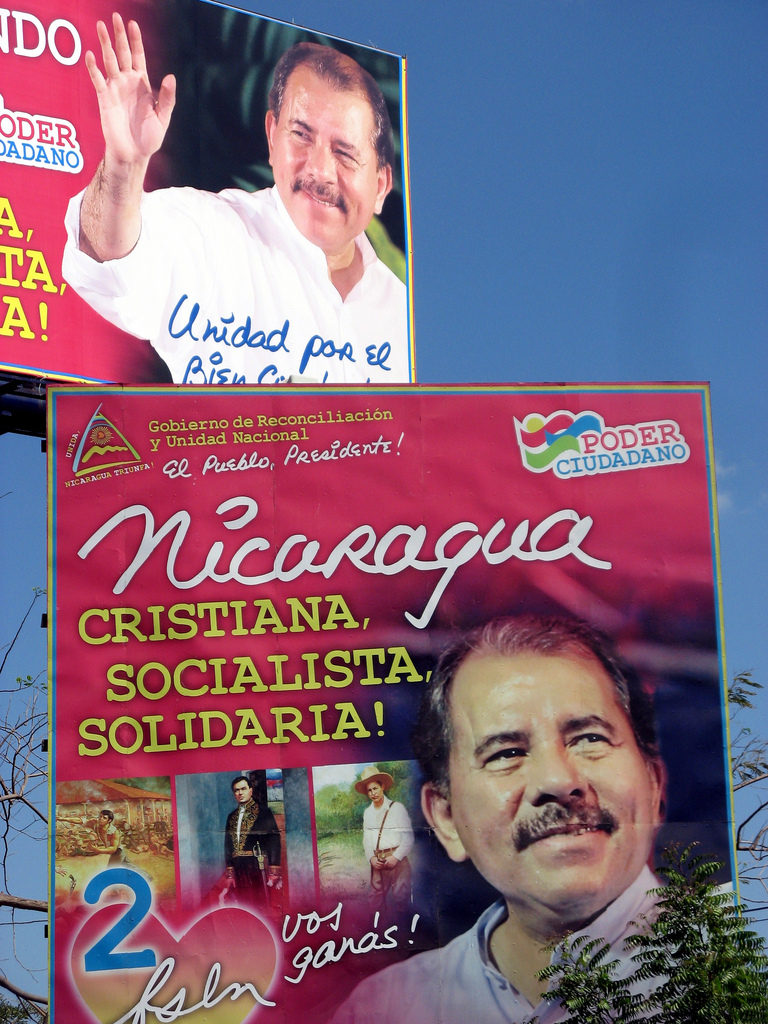

Located in the picturesque Central American isthmus, the Republic of Nicaragua rests upon a land with the same immensely rich pre-Columbian past shared by all Latin-American nations. However, since April 18th, this country of jungles, volcanoes, lakes and enthralling beaches is the scenario of a widely documented, yet largely unaddressed, series of persecutions and killings of dissidents by President Daniel Ortega’s police and paramilitary forces. By July 10th, the number of deaths far exceeded 350, of which at least 305 belonged to the civil society. Notably, according to the Organization of American States (OAS)’s Inter-American Commission of Human Rights, pro-government subjects perpetrated more than 90 per cent of these homicides. Together with Rosario Murillo his wife and Vice-President, the Nicaraguan dictator (one of the vestiges of autocratic leadership in the region) has given ample evidence of his desire to immortalize himself as the successor of tyrants like Somoza, Videla, Fujimori and Pinochet.

Daniel Ortega, born in La Libertad, Nicaragua in 1945 has served as the 62nd President of Nicaragua since 2007. However, his political career spans over four decades. Ironically, from a young age, Ortega revolted against Anastasio Somoza’s government –one of Nicaragua’s most cold-blooded dictatorships. He became a ‘Sandinista’ in 1963 (that is, a member of the Sandinista National Liberation Front, more known as ‘FSLN’ for its initials in Spanish) and his various contributions to the party resulted in his arrest in 1967. This socialist party was named after Augusto César Sandino, leader of the Nicaraguan resistance movement against the United States occupation of the country between 1912 and 1933.

Following Ortega’s release seven years later, he traveled to Cuba in order to receive formal training in guerrilla warfare from Fidel Castro’s regime. After Somoza’s exile, Ortega was in charge of the Junta of National Reconstruction, which ruled from July 1979 to January 1985. In fact, in 1984 he won the presidential elections with over 60 per cent of the voters’ support. This first period –which embraced Marxism-Leninism— paved the way for his thereafter-populist governing style, as he implemented measures that were radical at the time, such as a program of nationalization, the reform of land property, the redistribution of wealth and literacy programs. All of these features are reminiscent of the massive expropriations and monopolization of economic activity under Juan Velasco Alvarado’s dictatorship (1968-1975) in Peru.

Confident that the Nicaraguan people would trust him again, Ortega decided to participate in the 1990 general elections. Nevertheless, publisher Violeta Chamorro, who was the leader of the opposition alliance known as ‘Unión Nacional Opositora’ (transl.: National Opposition Union), defeated him, becoming the first elected female head of state in the Americas. Despite unsuccessful candidatures in both the 1996 and 2001 elections, in 2006, the stars aligned once again in Ortega’s favour (at least that is what he wanted everyone to believe). Rather, showing to what extent he is able to deceive and conspire against his opponents, he gave the false impression of having experienced a radical transformation of his political orientation (which had supposedly become more sympathetic with democratic values), coupled with a religious conversion to a sympathetic and philanthropic leader.

Soon enough, however, this masquerade disappeared and Ortega consolidated his absolutist ruling of the nation. Last year, by virtue of the Global Magnitsky Human Rights Accountability Act, the Trump administration accused Roberto Rivas (the former President of Nicaragua’s Supreme Electoral Council and one of Ortega’s closest allies) of managing fraudulent elections in 2006 and 2010. Moreover, it is Ortega’s close ties with the socialist government of Venezuela (which started in the time of Hugo Chávez and made Nicaragua a member of the Bolivarian Alliance for the Peoples of Our America) that have secured him consistent financial support in the form of generous donations from Venezuelan oil reserves.

Without this background, it is quite hard to comprehend the current political fiasco of the country and, by extension, the inhumane handling of the ever-growing opposition. Even though this year’s demonstrations (eventually cancelled after the first 30 casualties) started as a complaint against Ortega’s reforms on the pension and fiscal systems, the level of opposition to his government has been escalating for years now, leading to a national movement that prioritizes the wishes of the Nicaraguan people: namely, that Ortega leave power for good. The shadow of dictatorships, bloody insurrections, and capricious reforms has historically haunted all of Latin America. In the case of Nicaragua, the series of protests that started in mid-April constitute the “deadliest civil conflict” since the Nicaraguan Revolution (1979-1990). When the protests broke out in Managua, demonstrators were mostly elderly people, university students, teachers, and other activists from civil society. These days, the most salient faction of the opposition are students who sacrifice their lives on a daily basis. However, without Nicaraguan priests’ unconditional protection of demonstrators , the protests would have ended long ago. On July 13th, Ortega’s forces attacked the Rubén Darío University Campus (RURD). All of the students who could escape took refuge in the Church of Divine Mercy, which was surrounded by hostile forces until the early hours. Two students died and the church became a beacon of hope for those who continue fighting for their rights.

The day after Ortega’s forces were first seen using live ammunition on protesters, first lady Rosario Murillo made a public appearance to say they were “small groups, small souls, toxic, full of hate”, and assured the media that the marches would not continue. Furthermore, Ortega has systematically censored cable networks and radio stations to distort the real course of events. Journalist Ángel Gahona was murdered while reporting on the mass shootings of activists on Facebook Live, and Radio Darío was destroyed on April 20th by pro-government troops. Of course, the government’s reaction to the crisis has served as a catalyst for the strengthening of the opposition and the formation of an invigorated national movement against state oppression. On May 17th, the Inter-American Commission of Human Rights (IACHR) visited the country to assess the magnitude of the conflict in situ. According to Antonia Urrejola, Nicaragua’s rapporteur at the IACHR, the delegation demanded Ortega “to immediately cease the repression of the protest”. Needless to say, he did not hear them.

In a recent interview with Andrés Oppenheimer, Ortega denies the imputations against his government and is adamant that the number of deaths is less than 200. The spokesperson of António Guterres said the Secretary-General of the United Nations urges “all parties […] to refrain from the use of violence.” Apart from being late, this comment fails to condemn Ortega’s actions and communicates a wrong image of the conflict in which the protesters are also to blame. To make things worse, this tragic story has received the not so generous dividends of the international press, which has allotted limited spots to its (largely incipient) coverage. This is in consonance with the World-Systems Theory developed by sociologist Immanuel Wallenstein, according to which core countries’ media outlets seldom cover news about periphery countries.

Thinking about the past of Latin America still conjures up an image of mostly autocratic, repressive and corrupt regimes. Nowadays, Nicaragua and Venezuela are the residues of such an infamous legacy. Like all dictatorships, Daniel Ortega’s government plays havoc with the very basic rights that help us preserve our human integrity. There is simply no more time for pitiful updates. At this stage, it is clear that the only viable solution is for the international community to force the governing couple out of power in order to call for new, democratic (in every aspect that word entails) general elections. For the truth is that, as long as the Ortega-Murillo tyranny has control of the country, both the number of protests and the death toll will continue to increase, and, perhaps more importantly, the future of Rubén Darío and Sandino’s nation will become more and more uncertain.

Angello Alcázar is an undergraduate student at McGill University pursuing a Joint Honours degree in Sociology and Literature.

Edited by John Weston