Opinion | Canada is Quickly and Quietly Falling Behind in Humanitarian Aid Spending

https://images.app.goo.gl/vRFxLdUt6RJjqSUq9

https://images.app.goo.gl/vRFxLdUt6RJjqSUq9

There is no justifiable way to spin how little Canada currently spends on foreign aid. One could say the numbers speak for themselves, but until one is on the ground bearing the immediate consequences of this abysmal deficit it is difficult to understand how appalling the situation really is. Canada is widely considered to be an international leader—an icon for peace, politesse, and democracy, revered by organisations and countries around the world for being a staunch advocate of human rights, women’s and LGTBQ+ rights, diversity, and multiculturalism—and yet, when it comes to advancing these freedoms abroad, Canada falls short. While Canada isn’t perfect (as can be seen by its fundamental lack of concern for indigenous populations and its inadequate environmental policies), the values emitted by this North American nation are largely net-positive and net-progressive, making the lack of global action shocking and somewhat contradictory.

As of September 2019, Canadian foreign aid spending was at a scant 0.28% of the Gross National Index (GNI), putting it significantly below the UN target of 0.7% of GNI and below several of Canada’s key economic partners and allies. With such extraordinarily low funding, Canada is failing to support international efforts to promote peace and advance human rights in countries that are highly dependent on developmental aid. Currently, the majority of Canadian foreign aid is going to countries across Africa and Asia, with the bulk of the spending—65-75%—being channeled through the Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA). While CIDA was initially founded in 1968 as a government agency, it was absorbed into the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in 2013 under the Harper government. This move, unsurprisingly, added a multitude of bureaucratic measures and has made the agency’s operational mandate unclear, thereby restricting its efficiency in distributing humanitarian aid.

The money that the federal government does put into humanitarian aid is funneled through both bilateral and multilateral channels to fund different projects around the world. These projects change regularly but tend to focus on the promotion of equal rights, equal opportunities, transparency, and sustainability, particularly among marginalized populations. For example, the Feminist International Assistance Policy, one of Canada’s leading humanitarian aid projects, focuses on the empowerment of women as a method of eradicating poverty. This program involves creating channels for feminist discourse and ensuring equal opportunity and representation of women in all fields and sectors, including women in environmental advocacy to tackle the disproportionately gendered impacts of climate change. Although such projects are ongoing, they are limited in scope and impact due to a lack of funding.

While Canada’s apparent disregard for foreign aid is inexcusable, other countries seem to be following a similar pattern, albeit not to the same extent. In 2018, global foreign aid spending dropped by 2.7%, despite the increase in the length and gravity of humanitarian crises around the world. And while all countries above a certain national income level have a moral responsibility to fund a specific quota of humanitarian aid programs, the G7 nations have a particular obligation. These are countries with some of the highest GDPs and some of the highest reported qualities of life, with Canada even leading pact; if they cannot be bothered to help those in need, who will?

Of the G7 nations, the UK, Germany, France, and the United States are key players on the international stage. The UK, having incorporated the UN target into British law in 2013, has consistently met the 0.7% threshold in the last six years, making it one of only five countries to meet the target in 2018. Germany succeeded in meeting the 0.7% target in 2016, and while it has slipped slightly in the last few years, docking 0.61% in 2018, it is still significantly ahead of Canada. In addition to their foreign aid funding, German Chancellor Angela Merkel is also an outspoken advocate for humanitarian aid, citing immigration reform, refugee crises, and terrorism as specific targets for German engagement. France spent a reported 0.43% in 2018, and although this a leap down from the 0.7% target, French Official Development Assistance (ODA), the official measure of ‘donor effort’, has risen more in the last several years than any other official donor, signaling a steady future increase, unlike in Canada, where ODA appears to be on the decline. The U.S. differs slightly from the other countries in this economic bracket in that its percent allocation is the lowest, but its dollar funding is the highest. With the highest GDP in the world, a mere o.17% of GNI corresponded to whopping $34.26 billion in ODA spending in 2018, far outpacing the UK at $19.40 billion, Germany at $24.99 billion, France at $12.15 billion, and significantly topping Canada’s feeble $4.65 billion.

Comparative OECD chart outlining the different distributions of per country ODA spending.

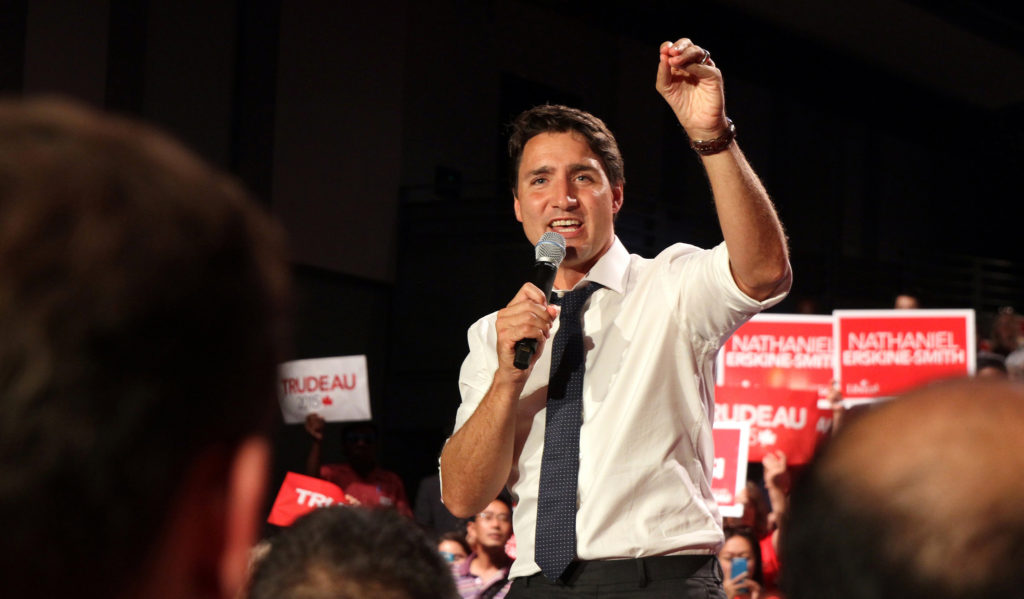

These numbers indicate some positive national trends, but not enough is being done as a global collective. The 0.7% target has been in place since the 1970s and, yet almost fifty years later, only a handful of countries are successfully meeting or exceeding the goal, and many, including Canada, are exhibiting a downward trend. Although Prime Minister Justin Trudeau has pledged to increase foreign aid spending, the numbers continuously fail to match his impassioned promises. Eventually, in 2018, he admitted that it would cost Canada too much to reach the UN target of 0.7% and has instead focused his attention on campaigning for a temporary seat on the UN Security Council (UNSC). While a seat on the UNSC would give Canada greater sway in international affairs, it does not detract from Trudeau’s domestic and international deficit. In fact, humanitarian aid spending has significantly decreased under Trudeau, moving from 0.31% of GNI in 2012 under Harper to 0.28% as of the latest report. While some of this can be attributed to the confusion surrounding the rebranding of CIDA, most of this decline is due to Trudeau’s careless spending across domestic sectors. By the end of his term, the Liberal government will have increased federal debt by 5.6%, more than any other prime minister in the country’s history, excluding those who were in office during a war or recession.

It therefore comes as no surprise that Canada’s other national political parties, vying for victory over the incumbent Liberals in the upcoming elections, are focusing their attention on decreasing this monstrous debt, and the easiest way to do this is to cut funding in areas where there will be the least domestic impact: foreign aid. Andrew Scheer, the leader of the Conservative party—Canada’s official opposition—has promised to cut foreign aid funding by 25% and instead use these funds to finance domestic policies in his party’s platform. Scheer has justified this decision with a slew of statements that have since been deemed false by policy experts. Scheer claims that a significant chunk of Canada’s foreign spending under Trudeau was, and is, going towards “middle- and upper-income countries” and “repressive regimes.” Experts have been quick to debunk these claims, with many even expressing confusion over what Scheer means by these sweeping and unsubstantiated assertions.

Jagmeet Singh, the leader of the New Democratic Party (NDP), has criticised Scheer and the Conservative party for these cuts, instead claiming that Canada has enough money for “domestic social programs and international assistance,” pledging to work towards meeting the 0.7% target should the NDP be elected on October 21. While admirable, one should take the NDP’s statements on foreign aid with a grain of salt: their platform hardly addresses international aid and fails to even mention China or India, two of the biggest forces in global politics today. When asked about the NDP’s foreign policy, Mr. Singh cited Canada’s role as an international peace-keeper and its duty to call out countries, like China, for their human rights abuses, but failed to mention any actual plans to realize these promises and hold relevant stakeholders accountable. The NDP’s commitment to promoting Canadian peacekeeping efforts is particularly pertinent given the significant reduction in the number of soldiers that Canada has deployed to UN service under Trudeau.

Elizabeth May, the leader of the Green Party, has also criticised the Conservative platform, mainly voicing her concerns over Twitter where she has also repeated her party’s pledge to increase foreign aid funding. However, in both her party’s platform and in her responses, May pledges to meet a UN target of “0.7% of GDP”, seemingly mistaking GDP for GNI. GDP corresponds to the income made within a country’s boundaries, including income generated by non-citizens, whereas GNI corresponds to income generated by all residents of a country, even abroad. While the difference between the two might seem insignificant, it would translate into a variance of about $182 million USD less in foreign funding and with Canadian funding already on the decline, this is worrisome.

While Scheer wants to cut foreign aid, Greens commit to “making poverty history” at 0.7% GDP in ODA. The Liberals have failed here. Only CPC makes Liberal aid levels look good. #MakeScheerHistory #GPC #SDGs

— Elizabeth May (@ElizabethMay) October 2, 2019

Elizabeth May’s tweet criticising Scheer and re-stating the Green Party’s target for foreign spending.

It is unclear whether Canadian foreign aid funding will increase any time soon. Even those, like the current Prime Minister, who profess high humanitarian aid targets, seem unable, or unwilling, to act on their promises. The slew of empty pledges and false claims have muddled the discourse on Canadian spending, making substantive conversations between federal parties and key stakeholders difficult to discern. As Canada struggles through another federal election, a number of important issues are on the table but foreign spending does not appear to be one of them. The Munk Debate, Canada’s only federal election debate on foreign policy, was canceled only a week before it was scheduled because the Prime Minister refused to attend. This, in addition to the existing deficit and the apparent lack of Canadian concern, has further limited the already insufficient dialogue on Canadian foreign spending, jeopardizing Canada’s future as a leading global human rights advocate.

The feature image “International Response to Hurricane Katrina” by Jeremy L. Grisham (credit: US Navy) is licensed under CC Public Domain Mark 1.0.

Edited by Shirley Wang and Alec Regino.