Past, Present, and Future: The Monroe Doctrine

https://flic.kr/p/WMNb2o

https://flic.kr/p/WMNb2o

The hemispheric hegemony of the United States is not a recent or underdeveloped phenomenon. The Monroe Doctrine, which solidified the US’s claim as the ‘rightful protector’ of Latin America, has existed since its inception in 1823. Created to ward off hungry European colonial powers, the doctrine has kept Latin America safely tucked into the United States’ back pocket for decades. It has been a significant piece of US foreign policy since its inception, shielding the region from neocolonial investment and Soviet influence during the Cold War. Latin America has always been regarded as America’s “geopolitical backyard”, and protecting the region from foreign influence has always been integral to US foreign policy. Until now, that is.

Once the Cold War ended and the US became a global (rather than simply regional) hegemony, Latin America lost its geopolitical importance. In 2013, John Kerry declared that “the era of the Monroe Doctrine is over”. Trump foreign policy seems to continue this trend. The “America first” rhetoric, coupled with a tendency to only mention Latin America in the context of drugs, the border wall, or NAFTA renegotiations, seemed to reject everything the Monroe Doctrine stood for. A pillar of US foreign policy for nearly 200 years has finally crumbled, and Latin America is free to look beyond the constraints of the Western Hemisphere, much to the chagrin of the Trump administration.

Enter China, and what is considered to be the most expansive infrastructure project ever – the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). The initiative itself is composed of two separate plans: the ‘Silk Road Economic Belt’ (the Belt) and the ‘21st Century Maritime Silk Road’ (the Road). The Belt is a series of overland transport routes, connecting the entire Asian landmass. The Road is actually a sea route, meant to link African, Mediterranean, and Latin American ports. According to the global consultancy group McKinsey, the plan has the potential to “cover about 65 percent of the world’s population, about one-third of the world’s GDP, and about a quarter of all the goods and services the world moves”. China touts the plan as a pinnacle of globalization, free trade, and cooperation, but long and short term impacts are uncertain, and reactions to the massive project are mixed.

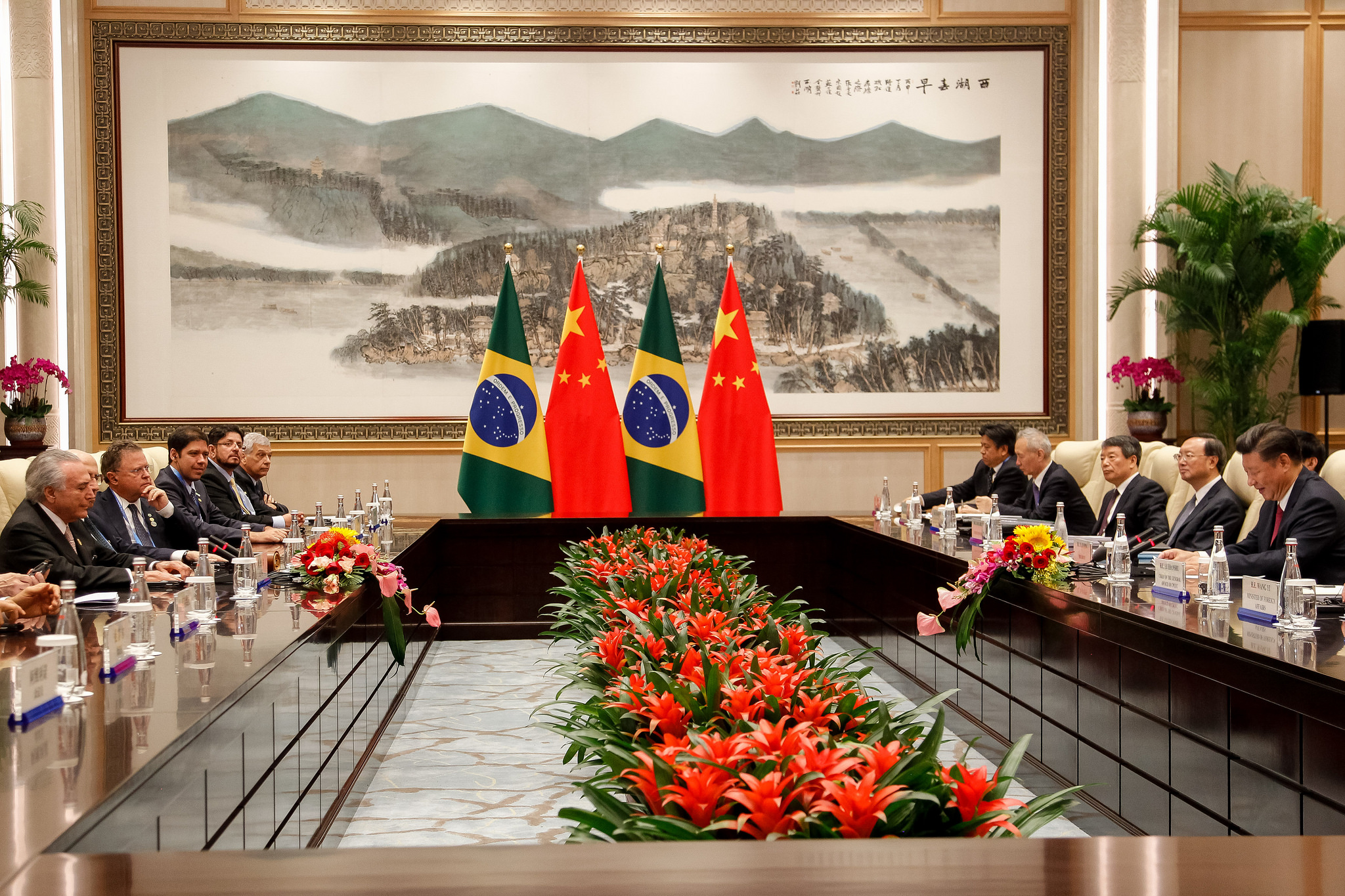

Already operating in full force in Asia and Africa, the Chinese project is expanding to an eager Latin America. China is already the largest trading partner of Argentina, Chile, Brazil, and Peru, and has plans to invest $500 billion in trade and $250 billion in direct investment by 2019. While China has been investing in Latin America for years, the kinds of investments have been changing. China is a long time investor in Venezuela’s oil sector, and is one of the main holders of Venezuelan debt. Now, China is diversifying holdings across the region. From power plants in Brazil to railways in Argentina, Chinese investment in infrastructure is growing.

The overall aim of the BRI appears to be economic development, but the direct benefit to China is massive. Every dollar invested in infrastructure can also be counted as an investment in Chinese soft power. China wants to increase its standing both regionally and globally, and, more than anything, it is clear that the initiative will have geopolitical ramifications. What does the BRI mean for near isolationist US foreign policy, and what impact will it have on Latin America?

United States foreign policy is currently in a state of disarray. Even before Secretary of State Tillerson’s immediate departure, there were few concrete policy points. “America first” does not correlate well with sweeping hegemonic prowess, which comprised much of American foreign policy over the past few decades. American non-involvement in Latin America is part of the reason for the sudden turn to Chinese investment, which in turn might be to blame for Tillerson’s comments praising the Monroe Doctrine in February. Citing the US’s historic role as protector of Latin American from foreign interests, Tillerson bashed the BRI as a form of colonialism via “imperial powers that seek only to benefit their own people”.

At this point, it seems as if the US is either unable or unwilling to strengthen, or even maintain, its position as the global leader. The potential ramifications of this have been widely speculative, but the new world order won’t be as favorable to American interests as the previous. A China overflowing with soft economic power is on the rise, and the United States must decide whether this is a viable enough threat to their interests to reestablish a Monroe Doctrine policy regarding Latin America. The trade war against Beijing Trump is currently engaged in seems to point to a new wave of protectionary actions, but there has been no action on any other front. There are two foreign policies coming from Washington at the moment – what Trump wants and what the actual bureaucracy does. This uncertainty, coupled with the nationalist rhetoric and protectionary pandering from the Trump administration has a number of countries spooked, and has inspired many to seek partners from outside of the American sphere of influence. Following Tillerson’s departure , it is unclear whether a new Monroe Doctrine-esque policy is on the horizon, or if the comments were simply reactionary pandering to a lost age of American hegemonic power.

Edited by Phoebe Warren