Reactions to Ukraine’s New Language Law

In April’s final weeks, Ukraine faced several pivotal moments as a country. With the presidential election having come to a close, the Ukrainian people voted in favour of Volodymyr Zelensky, the comedian turned politician, who campaigned on a platform of antiestablishmentarianism. Before Zelensky’s win, former incumbent Petro Poroshenko passed a law which officially gave the Ukrainian language special status in the country. It’s provisions guarantee that Ukrainian film distribution firms and television companies diffuse content which is up to 90% Ukrainian, and for “printed media and books to be at least 50%” Ukrainian. Most importantly, the law ensures that all employees of the public sector — such as government officials, teachers, and doctors — must communicate in Ukrainian when at their position of employment. As such, the new language law declares Ukrainian as the official language of the state.

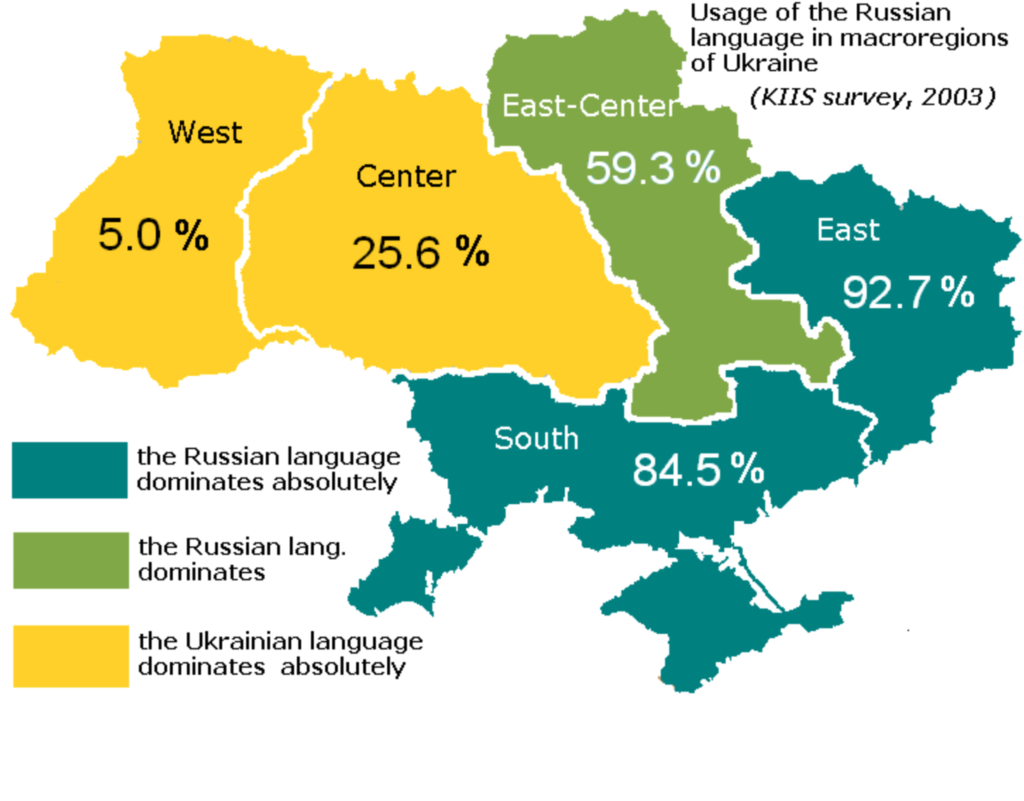

Depending on which figures are consulted, approximately 67% of Ukraine’s population speaks Ukrainian, while 24% speak Russian. In terms of Ukraine’s ethnic demographics, approximately 77.8% of the population is Ukrainian and 17% are Russian. It is noteworthy to highlight the disparity in Ukraine’s ethnic and linguistic demographic figures, as they demonstrate that while there is a small proportion of ethnic Russians within Ukraine, there is still a significant proportion of ethnic Ukrainians who communicate more in Russian than in their official language. In fact, a survey conducted by the Kiev International Institute of Sociology demonstrated that 39.6% of Ukrainians overall claim Russian as their native language. Therefore, although only 24% of the Ukrainian population can speak Russian, more individuals than expected are able to identify with Russian as their native language compared to Ukraine’s official language.

Map of Ukrainian and Russian language dispersal throughout Ukraine. *Figures are from 2003.

To explore the linguistic tension within the country, one must consider the role of the mass media in shaping the spread of both languages throughout Ukraine. The distribution of newspapers across the country is often referred to in an effort to demonstrate the growing presence of Russian speakers within the country. For example, total newspaper prints in Ukrainian outnumber those in Russian. However, Russian periodicals, which are published more frequently, vastly outnumber the amount of Ukrainian print periodicals. As such, most copies of printed newspaper publications are in Russian. The prevalence of Russian is not only limited within printed mass media, but is also prevalent among several Internet websites. For example, there is a large number of Russian-language information websites, along with Ukrainian e-retailers, who simply don’t have Ukrainian-language translation options on their website based on the assumption that the “Russian language is understandable by the absolute majority of Ukrainians.”

In current Ukrainian society, there are observable growing trends of bilingualism within the country. This is partially a result of the historical weight each language posssesses within the country, combined with the languages’ unequal territorial spread and the influence of mass media. The passing of the bill represents a historical moment among those in Ukraine who have fought for the preservation of and the unique right to their own language. Supporters of the bill have championed Poroshenko’s efforts to increase the prevalence of Ukrainian within the country, some claiming that the upholding of Ukrainian is a way in which the country can distance itself from its Soviet past. Historically, the Ukrainian language has consistently been under threat of prohibition, with over 60 bans on the language throughout the country’s history under foreign rule. In more recent history, the legacy of the Russian Empire and the USSR’s principle of Russification have contributed to the demise of Ukrainian throughout Ukraine.

Anti-Russification poster from 1930’s USSR. Translation: “Ukrainian School for Ukrainian Kids!”

In stark contrast to the bill’s supporters, there are still large parts of Ukraine which believe that the Russian language holds a certain prestige in comparison to Ukrainian, with some even claiming Ukrainian as a ‘vulgar peasant dialect.’ In fact, post-Soviet era figures demonstrate how the number of Ukrainian-language identifying Ukrainians has decreased over time. In dealing with the complexities interrelated between language and Ukrainian identity, the development of surzhyk arose, a mixture both of Ukrainian and Russian, which combines different dialects from both languages and can be broadly categorized as “Sovietized” vs. “post-independence,” and “urban” vs. “peasant” surzhyk.

The sensitivity regarding language in the current Ukrainian political context is a large product of the 2014 Russian annexation of Crimea. In April 2014, the Kremlin released a statement declaring Russian-speaking foreigners and “stateless people living on Russian territory” as legitimate conditions for obtaining Russian citizenship. As such, the Kremlin’s new policy was issued as a means to fortify their land claims in Eastern Ukraine, fast-tracking the citizenship process for Ukrainians living in the pro-separatist regions of Crimea and the Donbas. The Russian Interior Ministry’s Central Office for Migration has reported that approximately 86% of those living the Donbas want to obtain Russian citizenship. However, according to the Pew Research Center, 58% of Russian speakers in Eastern Ukraine want to remain united. Only 12% in Crimea, specifically, wish to remake Ukraine’s current borders.

At the heart of Ukraine’s language tensions, the issue of defining a Ukrainian identity is most prominent. Ukraine gained independence from the Soviet Union in 1991 and subsequently made an effort to distance itself from its history in order to create a unique Ukrainian identity. However, several elements of the Russian culture have persisted and still resonate with many Ukrainians today. Eastern Ukraine, which shares its border with the Russian Federation, has naturally identified with several aspects of Russian culture, while Western Ukraine is largely oriented towards the West and Euro-Atlantic policies. The underlying battle in Ukraine’s current political struggles can therefore be found when considering the fundamental question: should Ukraine be a monocultural or pluricultural society?

Former President Petro Poroshenko spent a significant part of his political career focusing on pro-Ukrainian nationalism and strongly opposing pro-Russian sentiment. Poroshenko even banned several Russian social media platforms in Ukraine, such as VKontakte (VK) and Odnoklassniki, in efforts to curb Russian influence. Indeed, during his campaign in the recent Ukrainian elections, Poroshenko relied on anti-Russia rhetoric to gain supporters with his “Army. Language. Faith.” slogan. However, it is debatable to what extent anti-Russia talk from state actors actually influences Ukraine’s public discourse. Opinion polls on Russo-Ukrainian perceptions often fluctuate, with Ukrainians holding little opposition to actual Russians, but only towards Russian aggression. As Iryna Bekeshkina from a leading Ukrainian think tank, Democratic Initiatives, argues: “In getting Crimea, Putin has lost Ukraine.”

With regards to Russian aggression, the recent Zelensky election prompted Russian President Vladimir Putin to sign a law which would officially authorize the passportization of Ukraine’s south-eastern regions, where the country’s breakaway regions lie. The implementation of this passport law would be different from the Kremlin’s 2014 passportization statements, which only legitimized the passportization of Russian speakers, and not those living in Ukraine specifically. Such efforts echo the handing out of passports in the Georgian Republic’s breakaway regions of South Ossetia and Abkhazia, which were later declared as independent territories by the Russian Federation. In response to Russia, Ukrainian Foreign Minister, Pavlo Klimkin, wrote to Ukrainians on social media:

“I call on Ukrainian citizens in Russian-occupied territories not to accept Russian passports. Russia has deprived you of the present, but now it encroaches on your future.”

The Russian Federation has claimed that the handing out of passports within Eastern Ukraine is a humanitarian measure. Kremlin official, Vladislav Surkov, stated:

“Ukraine refuses to accept these citizens as their own, installing an economic blockade, not allowing them to vote, using military force against them. Having received a passport, these people will feel more secure and free.”

Tensions regarding Ukraine’s new language law reached a tipping point in the recent United Nations Security Council (UNSC) meeting on the law, where Russia expressed that Ukraine’s “struggle for national identity should not [have to] violate the rights of the Russian-speaking minority.” Evidently, questions regarding Ukrainian national identity are still to be debated.

While Poroshenko has strongly supported the law, Zelensky has stated that he believes it will only serve to complicate government procedures. A major part of Zelensky’s political platform lies in the fact that he wishes for Russo-Ukrainian aggression to end. With this in mind, Zelensky has maintained a pro-Ukrainian, yet cooperative attitude with the Russian Federation, in hopes of achieving ceasefire within his political term. In his inaugural address, where Zelensky dedicated a majority of his speech to the topic of the Russo-Ukrainian War, he stated:

“I know that from the soldiers who are now defending Ukraine, our heroes, some of whom are Ukrainian-speakers, while others — Russian-speakers. There, in the frontline, there is no strife and discord, there is only courage and honor.”

In keeping with Zelensky’s message of acceptance towards all Ukrainians in mind, perhaps the dilemma that is Ukraine’s national identity will finally be answered.

Edited by Shirley Wang