The Cult of Xi?

After the death of long-time leader and despot Mao Zedong in the late 1970s, Chinese heads of state have attempted to avoid the traits of a “personable” leader in an attempt to not evoke the image of the late ruler. Instead recent leaders have seemed to be more like introverted technocrats who tread lightly on the line between personal and professional. However, the current number one man in China, Xi Jinping, seems to be deviating from the mentality of past post-Mao leaders, reverting back to a Mao-like cult of personality, some experts believe.

At six feet, Xi is the tallest leader since Mao. This is an important physical attribute in the height-obsessed nation of China, as Xi towers over his subordinates both physically and politically. It is evident in the way in which Xi presents himself to those around him that he is no ordinary modern Chinese head of state.

Xi, a native to Beijing was born in 1953 and is the son of Xi Zhongxun. former revolutionary veteran and one of the founders of the Communist party. At age ten, Xi’s father was purged from the party, and five years later, at the height of the Cultural Revolution in 1968, was jailed. Xi was then forced to find work and ventured to the countryside in Shaanxi province. There he became Party secretary for the branch of the province, having been accepted into the Party in 1974 before being rejected nine times because of his father’s history with the CCP[1]. He then went on to study at Tsinghua University in Beijing in engineering, eventually graduating with a Doctorate in Law from the university with a questionable thesis[2]. Thus began nothing short of a steady rise to power. Xi served in four provinces throughout his political career as well as municipalities and even becoming president of the Party School in Fuzhou in 1990. In 2002, he was named the party chief in Zhejiang and took a strong stance on corruption after having faced virtually no political opposition or serious political scandal. Xi was elevated even further when in 2007, he was named to the nine-man Politburo Standing Committee, the highest decision making body in China. He went on to serve in various portfolios and finally in 2012 was elected as the paramount leader of China, his swift quest for power had come full circle[3]. Xi was now ready to lead China towards what he coined the “Chinese Dream”, or a new China, free of corruption and heading towards a path of economic and social renewal.

Xi, a native to Beijing was born in 1953 and is the son of Xi Zhongxun. former revolutionary veteran and one of the founders of the Communist party. At age ten, Xi’s father was purged from the party, and five years later, at the height of the Cultural Revolution in 1968, was jailed. Xi was then forced to find work and ventured to the countryside in Shaanxi province. There he became Party secretary for the branch of the province, having been accepted into the Party in 1974 before being rejected nine times because of his father’s history with the CCP[1]. He then went on to study at Tsinghua University in Beijing in engineering, eventually graduating with a Doctorate in Law from the university with a questionable thesis[2]. Thus began nothing short of a steady rise to power. Xi served in four provinces throughout his political career as well as municipalities and even becoming president of the Party School in Fuzhou in 1990. In 2002, he was named the party chief in Zhejiang and took a strong stance on corruption after having faced virtually no political opposition or serious political scandal. Xi was elevated even further when in 2007, he was named to the nine-man Politburo Standing Committee, the highest decision making body in China. He went on to serve in various portfolios and finally in 2012 was elected as the paramount leader of China, his swift quest for power had come full circle[3]. Xi was now ready to lead China towards what he coined the “Chinese Dream”, or a new China, free of corruption and heading towards a path of economic and social renewal.

Xi prefers to compare himself to Deng Xiaoping, the first leader after Mao; a leader that steered China out of economic hardship, ruling through a concept known as “collective leadership”. But Xi Jinping’s “flashy” style, widening grip on power and refusal to disclose information on his domestic policy seem more reminiscent of the populism of Mao Zedong. This is primarily seen through what seems to be Xi trying to consolidate power into his own hands. One of these ways was his “virtuous” quest to hinder the spread of corruption in China, such as when in late 2013, Xi announced that Zhou Yongkang, former member of the Standing Committee, would be investigated for corruption. Zhou, formerly in charge of the entire law-enforcement apparatus, is the highest-ranking party member to be investigated under corruption since 1949. It has been seen as an unwritten rule that current and former members of the Standing Committee are immune from such decisions, yet Xi is attempting to rid all influence of Zhou who posed a significant challenge to past General Secretary, President Hu Jintao. Xi even rounded up those who were closely associated with Zhou. Further centralizing his power, Xi has shrunk the Standing Committee down to seven members, from nine, and now heads various other committees, essentially dismantling the principle of collective leadership that leaders have ruled by for decades[4].

Personality also seems to matter to Xi a great deal, fashioning himself as an everyman who believes in top-down, grassroots politics; the media is even calling him “Uncle” Xi. A man who eats the same food, walks the same routes, and even perhaps watches the same movies as you, Xi has been quoted to be a fan of The Godfather and Saving Private Ryan[5]. Xi often visits small villages and lesser-known restaurants, such as in Beijing in 2013, when he showed up unannounced and even paid for himself.

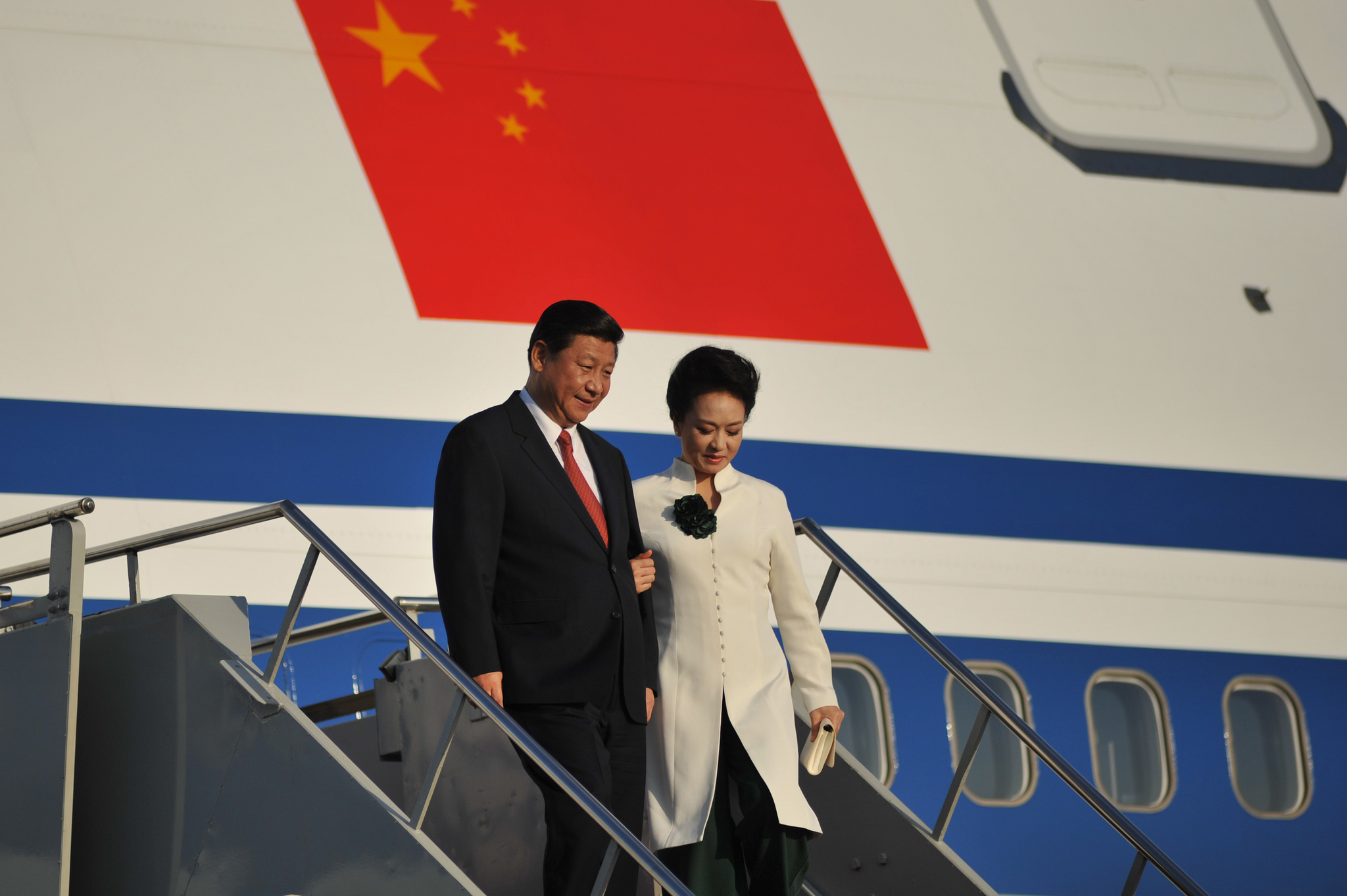

Xi has also been learning from Western political culture. It has been uncommon for a leader’s wife to be so prevalent in public ever since Mao’s wife had been arrested as being part of the infamous “Gang of Four.” However, Xi has no problem with his wife, Peng Liyuan, accompanying him in public, reminiscent of an American First Lady. He even permits (to an extremely small degree) some political lampooning on his part (though it was by a government-backed website that participated in it). In his first 18 months in office, Xi’s name has appeared in the People’s Daily, the CPC’s flagship newspaper, more frequently than eight current and past Chinese leaders, according to a study done by Qian Gang, director of the HKU China Media Project; this is the most since the time of Mao Zedong[6].

Long gone are the fanatical days of the masses dogmatically waving Mao’s Little Red Book, but party-backed support for a leader has never been as high since the 1970’s during the height of the destructive Cultural Revolution. It seems as though popularity and power have now shifted into one man as opposed to the party due to the many changes made by Xi namely his clamping dowon on corruption, Mao-like charisma and Western-style politics. This being said, how will Xi handle this power he wields and what will he do with it? The question becomes even more pertinent now when looking at the pro-democracy protests in the special administrative region of Hong Kong. Will Xi modify the system in Hong Kong and risk appearing weak to his fellow Chinese, or will he revert to dislodging the protest by force, evoking memories of the bloody 1989 protests in Tiananmen Square? This will be a difficult decision to make but one thing is certain: it must be a quick and swift decision or he could risk his reputation as “Uncle” Xi and merely become written in history as but another tyrant to sully its pages.

__________________________________________________________________________________

[1] Watts, Jonathan (26 October 2007). “Most corrupt officials are from poor families but Chinese royals have a spirit that is not dominated by money”. The Guardian (London). Retrieved 30 Sept 2014

http://www.theguardian.com/world/2007/oct/26/china.uknews4

[2] The content of Xi’s thesis was said to have had little to do with law and may have perhaps been plagiarized.

See: Sheridan, Michael (11 Auguat 2013)”Objection, Mr Xi. Did you earn that law degree?” Retrieved 29 Sept 2014. http://www.thesundaytimes.co.uk/sto/news/world_news/Asia/article1298782.ece

[3] “Profile: Xi Jinping”. BBC News (London). Retrieved Sept 30 2014

http://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-pacific-11551399

[4] “The Power of Xi Jinping” (September 20th, 2014) The Economist (London).

http://www.economist.com/news/china/21618882-cult-personality-growing-around-chinas-president-what-will-he-do-his-political

[5] Vanderklippe, Nathan. “Xi Jinping taps into Mao Zedong” (March 25 2014) The Globe and Mail (Toronto). Retrieved Sept 30 2014.

http://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/world/behind-the-everyman-xi-jinpings-image-more-like-maos/article17675192/

[6] Wan, Fang. “Emboldening the “strong man” image” (December 7 2013) DW Akademie (China). Retrieved September 30th

http://www.dw.de/emboldening-xis-strongman-image/a-17822938