The Mythical ‘White Gold of Jihad’

After the deadly 2013 attack on the Westgate Mall in Nairobi, Kenya, several major news sources reported a supposed link between the illegal ivory trade and Al-Shabaab, the terrorist group responsible for the attack. Most, if not all, of the reports shared one shocking statistic: poaching may have supplied up to 40 per cent of funding for the group’s activities. The perpetuation of the narrative linking wildlife trafficking to international terrorist networks created an opening for the insertion of counterterrorism interests into global anti-poaching efforts, foregrounding global security interests to effective wildlife protection.

Notably, the reports attributed the finding to the same single source: a study conducted by the Elephant Action League (EAL), an anti-poaching NGO based in California. Originally published in 2012, the EAL’s study termed ivory the “white gold of jihad.” Despite its frequent citations, the study was not without scrutiny, primarily directed at its reliance on hidden camera footage (à la Seaspiracy) and a single unnamed source. In 2016, authors Andrea Crosta and Kimberly Sutherland republished their article, attempting to bolster its credibility. Still, few changes were made, though they added some unnamed sources from Somalian ivory trafficking networks and mentioned the well-documented, albeit likely exaggerated, link between Joseph Kony’s Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) and the illicit wildlife trade in the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

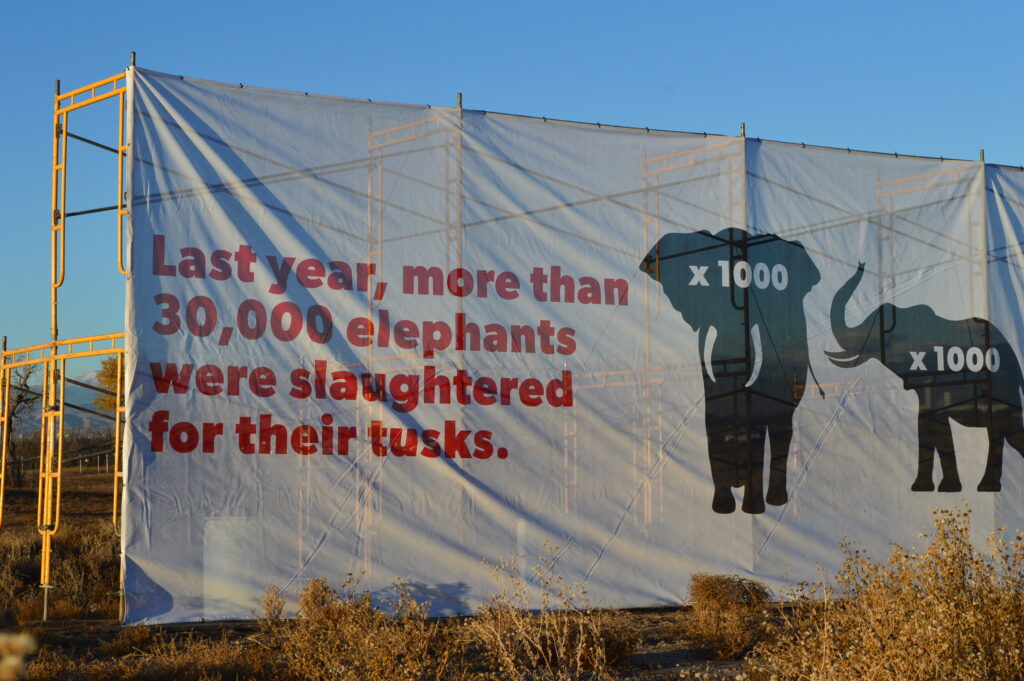

In 2013, the same year the EAL first published their study, the Clinton Global Initiative (CGI) pledged $80 million USD towards anti-poaching efforts. Then, in 2015, well-known Hollywood film director Kathryn Bigelow released her short film “Last Days,” which sought to call attention to the phenomenon of what she termed “ivory-funded terrorism.” Among Bigelow’s more widely known projects is the controversial 2012 film Zero Dark Thirty, a dramatization of the tracking and killing of Osama bin Laden that was widely criticized for its gratuitous depictions of CIA torture methods. The front page of the website for the Last Days film presents viewers with facts like “elephants in the wild could be extinct in eleven years” and “an elephant is murdered every 15 minutes.” These shocking conservation figures are featured directly adjacent to the claim that “African terrorist groups such as al-Shabaab, The Lord’s Resistance Army, Boko Haram and Janjaweed use the sale of illegal ivory to carry out attacks.” While no source is directly provided for these claims, the website links to the Clinton Global Initiative, the National Counterterrorism Center, and the EAL on a separate page.

This supposed ivory-to-terrorism revenue stream quickly gained traction on all sides of the political spectrum. In 2015, National Geographic labelled wildlife trafficking a “rare bipartisan issue in [the US] Congress,” as evidenced by the swift passage of the Global Anti-Poaching Act of the same year. Even if Crosta and Sutherland’s claims about Al-Shabaab’s potential ivory revenue are legitimate, their study was still admittedly limited in scope and evidence. Why then did it hold so much weight with international politicians and activist groups? At the time, several political scholars and journalists hypothesized that conservation NGOs like the EAL were capitalizing on post-9/11 global terrorism fears to access new avenues for financial and political support. But, what if the reverse were true? Almost twenty years after the attacks on 9/11, the climate crisis and its accompanying narratives of species endangerment and extinction are potentially even more direct avenues to the heartstrings and wallets of the general public than concerns over terrorism. As much as environmental protection can and should be a bipartisan issue, this creates the potential for it to be co-opted to advance other agendas, including military ones.

The EAL’s initial paper came when the US began ramping up counterterrorism operations in Sub-Saharan Africa. In response to the expanding reach of Islamist militant groups throughout Africa’s Sahel region, US foreign policy under both Obama and Trump included the deployment of special forces, numerous drone strikes, and support for local militaries through training and arms sales, all part of the so-called “global fight against violent extremism.” The Biden administration is beginning to exhibit its counterterrorism strategies in the Sahel, including support for France’s sustained military presence in countries like Mali. Promoting the narrative of “ivory-funded terrorism” could allow the US to maintain, and even increase, its military presence in the region while minimizing criticism from liberal circles.

In this new decade, the EAL is still playing a role in perpetuating the poaching-terrorism narrative. A brief look at their updated website reflects how closely intertwined anti-poaching and counterterrorism initiatives have become. Now operating under the name Earth League International (ELI), the organization calls itself the “Intelligence Agency for Earth,” referring to its “intelligence-based approach” to investigating and targeting transnational wildlife crime. The organization’s work is summarized by a three-pronged intelligence gathering strategy, whistleblowing, and media outreach. Among the team members are a former FBI agent and unnamed CIA operative, both with backgrounds in counterterrorism operations. Their roles are listed as including the “advis[ing] and train[ing of] domestic and foreign Intelligence agencies on undercover techniques and methodologies.”

There are numerous well-researched connections between climate change and global conflict, especially regarding resource scarcity and land insecurity. But, the complex socio-political impacts of global warming demand equally complex solutions. Applying one-size-fits-all policies and tactics of the Global War on Terror to issues like poaching is bound to do more harm than good — and potentially detract from more pertinent socio-economic drivers of transnational wildlife crime. Such blunt tactics are poorly suited for the highly localized nature of poaching. Introducing more foreign weapons and military power to regions like the Sahel will likely exacerbate instability and increase support for insurgent groups. It’s hard to imagine a scenario in which that would save any elephants.

Featured image “Confiscated ivory jewelry slated for destruction in the crush.” by USFWS Mountain-Prairie is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

Edited by Sara Parker