The Problems with Teaching U.S. Culture: My Experiences Teaching ESL in France

Globalization is often understood in economic and political terms, where success is a measure of international connectivity and the reach of these relations. Despite the various analytics used to measure an organizations’ or individual’s success, the foundation of these relationships is linguistic, where the basic ability to communicate is paramount. As a result, language studies have exploded over the last twenty years, as both individuals and societies have had no choice but to expand their linguistic capabilities and with it, their cultural awareness.

Language and Culture

More so than before, language studies have come to be understood as a unifying mechanism that has allowed individuals to connect with people in previously unimaginable ways, and while this is true to a degree, this relationship is not as symbiotic as it may seem.

For the last few weeks, I have been teaching English at a camp in Northern France whose objective is to immerse students in English and Anglophone culture, both inside and outside the classroom. |My official title is language counselor, and thus one of my main responsibilities is teaching ESL classes, or English as a Second Language, along with the more traditional responsibilities of a camp counselor. Initially, I viewed teaching as a positive opportunity to connect individuals of diverse backgrounds through linguistic and cultural experiences. Furthermore, coming from a language background myself, I was extremely impressed with the premise of this camp and its goal in providing students with the opportunity to immerse themselves in the language in which they are studying, as I have found this to be the best way to improve fluency in a language. Many of my colleagues, who work in the field have corroborated this as well. While these ideas are valid, the process and issues surrounding teaching and learning languages are far more complex, especially considering English’s role in westernization and neo-colonialism that both use language and globalization as a form of personal and cultural oppression.

The Role of Culture in Teaching Language

To many, language and culture are understood as synonymous and thus interchangeable terms. Culture acts as an extension of language, and consequently, the concentration falls on grammatical structures and idiomatic patterns. Language- as a communicative vehicle- is the primary focus and occupies a privileged position to culture and cultural studies in this relationship. The very construction of the phrase “Language and culture”, which is the phrase that many universities use to denote language courses and specializations, highlights this phenomenon. In this construction, the word culture appears as an afterthought. The argument for this is that an individual must possess sufficient knowledge of a language to understand its corresponding culture, and while there is some truth to this-as the structures and nuances of a language are indicative of culture- this relationship is more complex and warrants further consideration.

The Non-Western Identity: Moving beyond Linguistic Identities

In non-western societies, like those in Latin America, Southeast Asia, and many parts of Africa, culture is one of the most basic forms of agency, acting as a foundation for the development of both an individual and communal identity despite increasing international intervention. Contrary to many western identities, such as Anglophones and Francophones, cultures outside this region do not generally define themselves linguistically, but instead by a common background, known as ethnicity. Ethnicity and culture, which goes well beyond language, function as the primary sources of identity, regardless if an individual speaks the language associate with this ethnicity. For example, only 73% of Latinos living outside of Latin America speak Spanish- a number that has dropped 5% over the last ten years. None the less, they still identify with the Latino community. A similar phenomenon can be seen amongst indigenous tribes in both North and Latin America as well. This cultural phenomenon has thus prompted a relatively new field of study known as ethnography, which utilizes scientific methodologies to understand and analyze culture and its development. While language is still a relevant point of consideration, it is not the only nor primary point of distinction.

Acknowledging Ethnicity in Western Regions

Anglophone culture, which falls under the larger category of western culture, is virtually nonexistent in the traditional sense. In places like Latin America, Southeast Asia, and Africa, culture is often defined in terms of ethnicity, but this distinction, or at least the degree of this distinction, does not exist in most western societies. In places like the US, Great Britain or even France, individual identities are prized over communal identities. There is not a defined culture in the traditional sense, but instead, a culture of individualism that can be seen in the political, economic and social structures of these countries

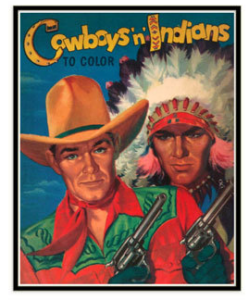

The individualized nature of western culture thus complicates cultural and language studies because there is no homogenized identity to study. Returning to the language camp, the organziation uses iconic elements of US history and pop culture, such as Hollywood and the Wild West, as opposed to more traditional markers of culture. These themes touch on the indivdualized ideal, as the themes themself praise indivduals over the group. To many, these two images are emblematic of US culture, and

while they may seem harmless, they are not as benign as they appear, especially considering the various racial and sexual scandals plaguing Hollywood as well as the romanticized images of the Wild West that ignore the trauma inflicted on indigenous communities. Furthermore, they are not necessarily representative of the individuals who live in the US, specifically the cultural minorities, like indigenous individuals, who live in the region yet possess a distinct culture.

Defining Culture in the West

The development of the West and its perception of culture is marked by a history of colonization that continues today in the form of neocolonialism and westernization. In the case of colonization, Europeans, and later North American, colonizers have used culture as the primary means of oppression, seeking to not only directly oppress the colonized through official channels, but also through less official channels, labeling their cultural identities and practices as inferior. During the westward expansion of the US- better known as Manifest Destiny-, the US Government not only removed indigenous communities from their lands, but they removed these communities and their ‘savage culture’, which came to anesthetize progress, from the US identity.

Consequently, colonized individuals lost control over their more official cultural channels, such as language and politics, and thus had to find other ways to retain their identity, such as through ethnicity. In teaching language, however, addressing this can be problematic because these minority groups are marginalized and underrepresented in a nation’s cultural identity, seeing as they do not form part of the common linguistic base of the culture in question. While indigenous tribes may not necessarily be Anglophone, they form a significant part of US culture and can still be represented in English.

Westernization follows a similar model, but there exists a stronger desire for assimilation- and even the homogenization-to western culture than with colonization. Western countries often try to manipulate and reconstruct marginalized cultures for their own advantage, most evident in the contemporary relationship between indigenous tribes and the US cultural identity that has latched onto parts of this identity, yet continues to isolate these individuals and their ‘othered’ culture.

All of this considered, language studies have experienced the repercussions of these complex relations so that the very significance of learning a language differs from region to region and even from individual to individual. For most western individuals, learning a language is seen as advantageous and useful for future pursuits while for many non-western individuals, it is seen as a necessity that jeopardizes their own cultural identity due to the dominant nature of western culture that defines non-western cultural identities as inferior.

Teaching US Culture

When teaching language, there must be more than a consideration of culture and the non-linguistic elements of culture. Culture is not synonymous with language. Culture is the broad category that language falls under, and as a result, culture is not restricted to language. Culture can be represented in other languages or even through non-linguistic mediums.

The camp provides its teachers and counselors with stereotypical images of indigenous communities that not only perpetuate negative stereotypes, but fail to provide a contemporary look at these individual who have and continue to form part of US culture. As a teacher, I have struggled to find ways to teach my students about indigenous communities that are accurate and relevant, but indigenous studies cover a large variety of expansive and complex issues that cannot be realistically covered in five days.

Furthermore, there are many other unethical and questionable parts of US culture that most US citizens find disturbing, yet these issues are either thrown out with little to no conversation or oversimplified to avoid controversy, such as gun violence. Further complicating this issue is the limited amount of English amongst students. The primary goal of the camp is to teach and assist students on improving their English, and thus it is not realistic to expect that they will be able to understand these complex topics, many of which are not understood by most US citizens. Age is another limiting factor, as many of the students are not mature enough to understand these issues in their native tongue. Finally, the students are removed from these issues and have no real stake nor investment them, seeing as they are from a completely different continent.

Rethinking Culture

The issue for language teachers thus becomes how to explain stereotypes and stigmas to non-natives when many native speakers still believe in these stigmas. If the goal is to emulate natives, it may be more accurate to perpetuate these stigmas, but this attitude will only continue to marginalize vulnerable communities who possess an equal right to the cultures in question. Ultimately, the problem boils down to culture and how societies, individuals and groups define and understand the term. Ethnography is certainty a positive step in the right direction and a valuable consideration for individuals teaching language, but it is not the final solution, as most ethnography still privatizes linguistic considerations and quantifiable concepts. The solutions for these challenging questions will require an interdisciplinary focus that not only utilizes the resources of various academic fields, but also works directly with all members of a culture to ensure that every voice is represented.

Edited by Sarie Khalid