It’s Time to End the State Sponsors of Terrorism List

President Donald Trump and Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu shake hands during their joint press conference, Wednesday, Feb. 15, 2017, in the East Room of the White House in Washington, D.C. (Official White House Photo by Benjamin D. Applebaum)

President Donald Trump and Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu shake hands during their joint press conference, Wednesday, Feb. 15, 2017, in the East Room of the White House in Washington, D.C. (Official White House Photo by Benjamin D. Applebaum)

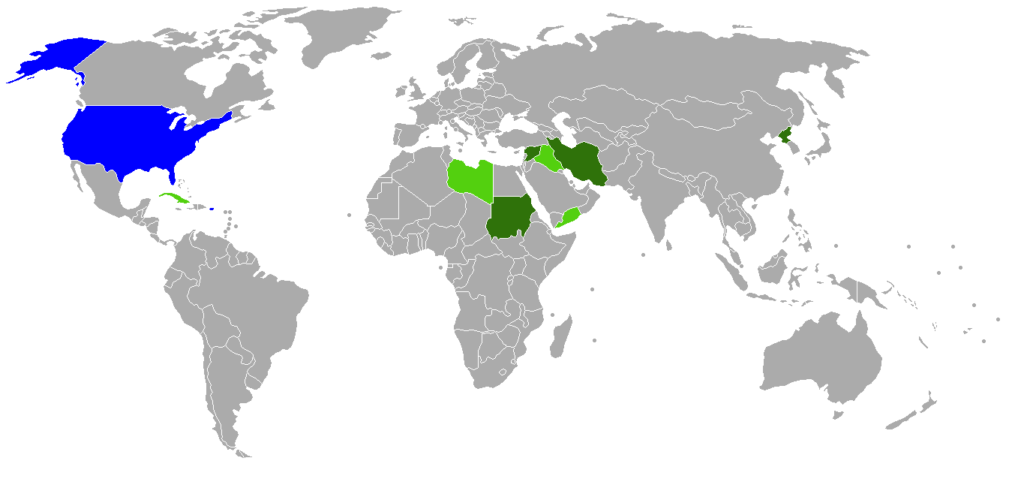

Since 1979, the United States State Department has kept a list of what it calls “state sponsors of terrorism.” According to the State Department, these countries have “repeatedly provided support for acts of international terrorism.” Such a designation triggers automatic unilateral sanctions, including a ban on arms exports and economic assistance as well as restrictions on anything that could be used to support terrorism or build the state’s weapons capability. At the list’s inception, it included four countries: Libya, Iraq, South Yemen, and Syria, three of which have either been removed or ceased to exist. Currently, its members are Syria, Sudan, Iran, and North Korea. Cuba, which spent over 20 years on the list, was recently removed as part of the Obama administration’s push to reestablish diplomatic relations.

Some countries on the list are clearly deserving of such a designation. Iran’s connections to Hezbollah, for example, are well–documented. However, over the years, some of the names on the list have not been states commonly associated with international terrorism. Take the case of Cuba for example: backing insurgent movements in Europe and Latin America landed it on the list in 1982. Though the FARC, a Colombian Marxist group that it supported, frequently used terrorist tactics against Colombian citizens, it never became an international terrorist organization. Cuba’s addition to a list of “repeated […] support[ers of] acts of international terror” is therefore utterly illogical. It is also hypocritical. During the Kosovo War, the US, along with its NATO allies, supported and funded the Kosovo Liberation Army, an organization it had itself branded as a terrorist organization. Should the US then have placed itself on the list?

North Korea’s status is just another inconsistency in a list full of them. Added in 1988 for bombing a South Korean airplane, which killed 115 people, it was removed twenty years after the initial attack by then President Bush. Though the attack was undoubtedly an act of international terrorism, it did not lead to a pattern of behaviour. Even the State Department conceded in 2007 that North Korea had not committed a terrorist attack since the bombing. Why, then, is it on a list for repeat offenders?

Some have defended North Korea’s place on the list by pointing to its arms shipments to both Iran and the Assad regime in Syria. But if giving arms or money to Iran is international terrorism, Russia’s addition to the list is several years overdue.

Despite occasional grumblings from politicians, including former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, North Korea remained merely an uncooperative nation until a few months ago. As part of Trump and Kim’s escalating war of words, it was re-added to the list on November 20th, 2017. In explaining his decision, Trump referenced the assassination of Kim Jong-nam, Kim Jong-un’s older brother, as well as the death of Otto Warmbier, an American student held in detention in North Korea after attempting to steal a poster from his hotel. Though both deaths are undoubtedly tragic, it is difficult to see how either of them qualifies as “acts of international terrorism.” If assassinations on foreign soil somehow qualify, Israel, a close ally of the United States, should be on the list many times over.

Furthermore, the problem isn’t only with the North Korean example, but with the inconsistent nature of the list in general. If Iran’s support of Hezbollah is enough to land it on the list, why is Lebanon not on the list for allowing it to participate and hold seats in its government? If harbouring those wanted by the United States was what kept Cuba on the list, why was Pakistan never added for shielding al-Qaeda? And what of Qatari support for Hamas, an organization considered by the US to be terrorist in nature?

When considering the exceptions and inconsistencies in the list, the almost inevitable conclusion is it is mere political symbolism. Cuba’s addition to the list, for example, came at the beginning of the Reagan presidency, which was characterized by a harsh stance towards communism. Adding Cuba to the list, regardless of whether or not it truly deserved to be there, allowed Reagan to signal that he was serious about fighting and ending communism. In the modern day, the list is used to signal enemies of the United States. Israel, Lebanon, Pakistan, and Qatar are not enemies; on the contrary, they are important strategic allies. By branding them as sponsors of terrorism and thereby limiting military cooperation (and informally declaring them enemies), the US would be hamstringing its own ability to combat terrorism in the region. Conversely, the United States almost never cooperates with Iran, Syria, Sudan, or North Korea. Placing them on such a list allows the United States to proclaim them to be morally inferior and to lose very little in the process.

If the list is pure political theatre, there is little reason for it to continue to exist. The sanctions it triggers automatically could be applied manually, with the annual report by the State Department still published. Being branded a “state sponsor of terrorism”, even without being added to an ostensibly comprehensive list, would still be an unwelcome categorization. The existence of the list itself adds very little to the conversation around terrorism and should therefore be phased out.

Edited by Benjamin Aloi