US Announces Military Withdrawal from Myanmar: Another American Foreign Policy Quagmire?

The US State Department has announced that it will be withdrawing military support from Myanmar in the coming weeks as well as suspending all travel waivers for Myanmar military officials, amid the ongoing infighting between the Rohingya people and the country’s military forces. This decision has come after months of devastating human rights abuses instigated by the military against the Rohingya people in the western Rakhine state of the country. Since August 25th, 2017, following retaliative attacks against the military by members of the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army, conditions in the Rakhine state have rapidly deteriorated, yet the country’s majority government, the liberal and democratically-elected National League for Democracy (NLD), has remained relatively mute on the issue. While political circumstances in Myanmar are complicated and constitutional restrictions prevent the NLD from exercising full, legal power, the United States cannot continue to support a military unit that is actively engaged in what many are calling ethnic cleansing. The United States was one of the first Western countries to support Myanmar’s democratization efforts back in 2009 under the Obama administration, and has since made significant headway in reinstating diplomatic and trade relations with the Southeast Asian country. Recent developments, however, threaten to jeopardize this progress.

Between the military coup in 1962 and President Obama’s victory in 2008, diplomatic relations between the United States and Myanmar were strained. The first US sanctions were placed on Myanmar in 1988 following a surge of mass protests, many of which were student-run, and additional sanctions were placed under President Bush in 2003 through the Burmese Freedom and Democracy Act, as conditions continued to worsen. In 2007, the United States Department of Treasury froze the assets of 25 high-ranking Myanmar government officials, in an effort to restrict the military’s uncurbed power, but few improvements followed. In 2008, the United States passed the JADE (Junta’s Anti-Democratic Efforts) Act, which imposed further sanctions on Myanmar by prohibiting the importation of gemstones, notably jade and rubies, from Myanmar into the United States. This attempt, among others, to coordinate international efforts and “restore civilian democratic rule to [Myanmar]” neither helped the struggling people of Myanmar, nor restrained the military’s authoritarian power.

In 2009, following President Obama’s victory and Hillary Clinton’s appointment as Secretary of State, a new set of policies were outlined to help democratization efforts in Myanmar. As a result of long-standing frustration regarding continuous US failures in Myanmar, these new diplomatic efforts employed the use of sanctions as well as the use of engagement strategies. These strategies largely focused on increasing support for the NLD, as well as garnering greater international awareness of the history of oppression in Myanmar, in an effort to put pressure on the military to allow for democratic elections. In 2010, the military finally freed Aung San Suu Kyi from house arrest, and in the 2012 by-elections, the NLD won 43 of the 45 seats they contested, resulting in a resounding victory. The United States saw these developments as promising signs of democratic progress and, consequently, reinforced their commitment to reinstating diplomatic ties with Myanmar.

These ties provided Myanmar with the necessary support and aid to rebuild their devastated country. While preliminary reports did outline the need for national reconciliation, including the protection of Myanmar’s numerous ethnic groups, such as the Rohingya, the reports did not go any farther in addressing how this would be done. In 2015, after a decade-long fight for democracy, Aung San Suu Kyi led the NLD to victory in the first open elections in half a century. In 2016, near the end of his term, President Obama and Secretary of State John Kerry met with State Councilor Aung San Suu Kyi, and announced that the United States would be removing some of the economic sanctions on Myanmar, as substantial progress towards democratization had been made.

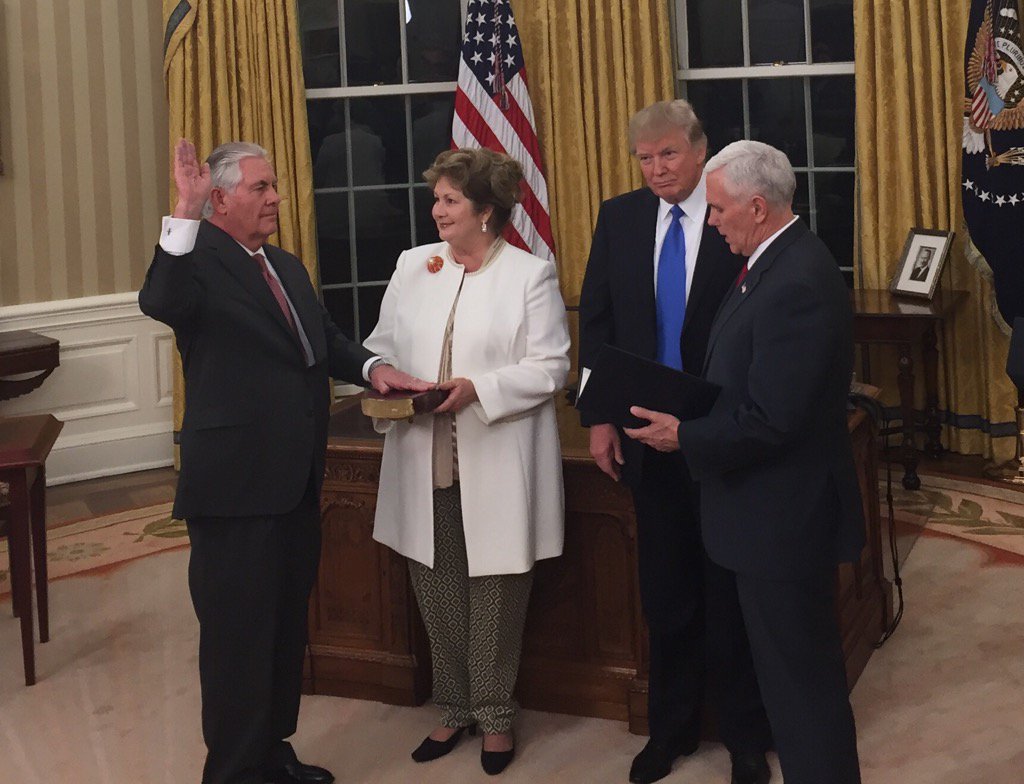

The prospect of a free and open Myanmar was short lived, however, and recent violence in the Rakhine state has reopened the debate as to whether or not US sanctions should be reinstated and to what extent. On October 23rd, State Department official Heather Nauert made a statement in which she announced that the United States is “assessing authorities” under the JADE Act to determine the best diplomatic efforts to put forward. In the State Department’s report, Nauert made it clear that Secretary of State Rex Tillerson holds Myanmar’s military leadership accountable for the atrocities being committed and the grave refugee crisis that has emerged as a result. While the Secretary did not elaborate on the role of the NLD government in the ongoing violence, he did make a distinction between the military and the democratically-elected government, alloting most of the blame to the former. Tillerson also stressed the need for an external, third-party investigation and fact-finding mission to put an end to the fighting and restore peace to this deprived nation. He accused Myanmar’s inherent militancy problem as the ultimate barrier to achieving this peace, and advocated for the military to be restrained and disciplined so as to allow foreign missions unbarred access to the region.

Secretary Tillerson also spoke with Myanmar’s army chief, General Min Aung Hlaing, prior to the state department’s release of this statement, in which General Hlaing, unsurprisingly, denied any and all culpability in the matter and “defended his forces against having committed atrocities.” This position is consistent with what the military has been claiming for months, while continuing to ignore those suffering from the very real and very dangerous crisis. In addition to withdrawing support, Tillerson has also been advised to take cues from some of his global counterparts, such as Secretary General Antonio Guterres and President Macron of France, and formally and publicly label the atrocities as a bona fide form of ethnic cleansing or even genocide. Official designations such as ethnic cleansing and genocide would not only garner significant, international attention, but invoke specific mandates and particular legal requirements.

All crimes against humanity that are labeled as such “require the United States to make a move to protect the population at risk and penalize the perpetrators.” Under the Genocide Convention Implementation Act of 1987, invoking the term genocide requires that immediate legal action be taken against guilty parties, typically by imposing a fine of up to $1 million and imprisoning lead actors for up to twenty years. The term ethnic cleansing is considered a slightly less severe term, and therefore does not carry the same legal capital as genocide, but invoking it would nevertheless have serious symbolic value and likely put implicit pressure on the United States Congress to take action against those responsible for the ongoing violence.

Supposed sanctions would likely be similar to those that restricted the country and crippled Myanmar’s economy for the last half century while the military was in power, which has led many within the United States government to question whether sanctions are the best course of action. While sanctions would send a message to the military that their violent tactics are no longer being tolerated by the United States, sanctions could also have serious consequences for Myanmar’s economy. Economic sanctions usually burden the targeted country with both economic and political instability, which would worsen the already fragile democratic structure. With a country already on the brink of another violent national crisis, adding more fuel to the fire by imposing sanctions would likely worsen the country’s chance of full national reconciliation.

There have also been recommendations from several United States senators, notably Senator Ed Markey, to place General Hlaing on what is known as the Specially Designated Nationals and Blocked Persons List (SDN), which blocks an individual’s assets and limits their travel. More than the direct effects of putting someone of high-rank on the SDN list, there is also the symbolic capital. Such a course of action sends a clear message to Myanmar’s military, as well as the entire world, that the atrocities being committed and championed cannot, and will not, be tolerated or permitted.

The best course of action is always the one that benefits the greatest number of people. While the United States is inclined to prefer policies that promote their national self-interest, many would deem it unjust for them to ignore or mistreat conflicts in which millions of people are suffering. The United States, widely seen as the designated global policing force, has a duty to help the Rohingya people, and it is imperative that this responsibility be handled fairly with all possible measures considered while still remembering the lessons of past endeavors.

Allegra is a U1 student pursuing a double major in Economics and Religious Studies. She is interested in the crossroad of religion and politics, specifically relating to democratization efforts in Southeast Asia.

Edited by: Thea Koper