Water, an Unkept Promise in Rural Africa

Food, education, gender equality, child health, maternal health, prevention of diseases, environmental sustainability, and global partnership: these are the eight Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) that the United Nations promised would accomplished by 2015.[1] All these goals are intertwined with Target 7C, a goal to “halve, by 2015, the proportion of people without sustainable access to safe drinking water and basic sanitation,”[2] which falls under the MDG of environmental sustainability.

Food, education, gender equality, child health, maternal health, prevention of diseases, environmental sustainability, and global partnership: these are the eight Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) that the United Nations promised would accomplished by 2015.[1] All these goals are intertwined with Target 7C, a goal to “halve, by 2015, the proportion of people without sustainable access to safe drinking water and basic sanitation,”[2] which falls under the MDG of environmental sustainability.

There are several issues with Target 7C’s progress. Although the “number” has been met for halving the proportion of people without access to drinking water, this number is not fairly distributed. There are observable discrepancies in the percentage of urban and rural people who have access to water, and even within a single community, the discrepancies between the rich and poor. The traditional practice of water-collecting also inevitably leads to deeper gender inequality, hindering young girls from attending school and mothers from becoming politically involved. The stagnancy in promoting sanitation leads to various health complications caused by open defecation.

According to UNICEF and WHO’s reports, the first half of 7C was accomplished in 2012, way ahead of the promised year. Between 1990 and 2010, 2.3 billion people gained access to improved drinking water sources such as piped supplies and protected wells, and 1.6 billion people have these sources connected to their homes or compounds.[3] Now, take a detailed look at these numbers: while 90% of Latin America, the Caribbean, Northern Africa and Asia have access to drinking water, only 61% of people in sub-Saharan Africa have access. The remaining 39% of sub-Saharan Africans compose 40% of the total global population without drinking water (approximately 780 million).[4]

Sub-Saharan Africa is the driest region in the world. Over the past four decades, Lake Chad lost 90% of its volume, disturbing 30 million lives.[5] There is no water for fish, crops and livestock, and this ultimately affects human food resources as well. Shortage of basic necessities naturally leads to insecurity and violent territorial conflicts over watershed usage. The younger generations migrate to inhospitable environments such as urban slums. Dramatic increases in the size of slums contribute to the escalation of communicable diseases, such as HIV and AIDS. When international partners finally sent 200 million USD to initiate the transfer of water from the Congo Basin to Lake Chad, it was too late to prevent the costs of severe desertification over the last decade.[6] The international community also continually opposes constructing dams in Africa for “environmental protection;” however, Bai-Mass Tal, Executive Secretary of the African Minister on Council on Water (AMCOW), argued that they have no right for others to oppose, because the dams in Africa are built to save lives whereas numerous environmentally-harmful infrastructures in developed countries are built for luxurious purposes.[7]

Disturbingly, the discriminatory distribution of water emerges not only between countries but also within countries. “Progress… has primarily benefitted richer people, increasing inequalities,” said Maria Neira, the WHO Director for Public Health.[8] Out of 345 million sub-Saharan Africans who still do not have access to potable water, 60 million are urban and 285 million are rural.[9] While 85% of urban people have pipelines or other improved sources of water in their complex, only 45% of rural people have the same type of access, and shockingly, 17% of rural people still use unpurified surface water from shallow lakes and puddles.[10] Additionally, the richest 20% in urban areas have 94% coverage of water, while the poorest 20% in rural areas only have 34%, as rural, low-income families lack the facilities for free water and lack the money to buy bottled water.[11]

40 billion hours a year are exhausted on collecting water, and most of these “water-fetchers” are women and young girls who have to carry back, on average, 44 pounds of water per trip.[12] The whole practice of water collecting violates a number of MDGs: children cannot attend primary school, women and girls have to sacrifice their time on physically-demanding tasks instead of development-oriented activities, and many children get injured on their way to find water or succumb to infections from the polluted sources. Because mothers are so preoccupied with collecting water, they cannot partake in political decisions regarding water distribution in the community, and as a result, most of the government investment is targeted towards irrigational infrastructure, rather than freshwater pipelines.[13] Sanjay Wijesekera, UNICEF Chief of Water, Sanitation and Hygiene despairs that “we are failing the poorest and the most vulnerable children and their families.”[14]

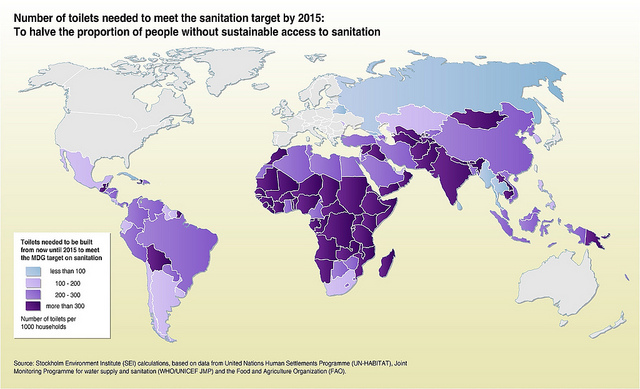

The other half of Goal 7C remains unaccomplished in most regions: only 63% of the population had improved sanitation access in 2012, and the figure is estimated to increase to 67% by 2015, which still falls short from the aim of 75%.[16] Open defecation is still practiced by 1 billion people over the world and sub-Saharan Africa is responsible for 20%.[17] A likewise gap exists between urban and rural facilities: 54% of urban communities have improved facilities compared to 31% of rural communities, and only 6% of urban people defecate openly while 32% of rural people do so.[18] Most African countries are failing to meet the commitments for implementing hygiene, due to burdensome debts and insufficient international funding towards Africa. Even worse, as a condition of receiving loans from the International Monetary Fund, governments have opened the water sector to privatization and exacerbated the existing gap for water access.[19] Bai-Mass Tal criticized that political leadership and advocacy in this development project must be maintained in order to effectuate the establishment of sinks and latrines, and that every official must approve all documents regarding water development for accountability and transparency purposes.[20]

Improper sanitation results in 368,000 deaths per year in sub-Saharan Africa.[21] Diarrhea is the most prevalent cause of death, but other common water-borne diseases include schistosomaiasis, caused by parasitic worms and leads to kidney failure, liver damage or bladder cancer, and intestinal diseases, caused by micro bacteria that reduce absorption of calories and ultimately contribute to malnutrition.[22] Water-borne diseases that originate from open defecation include poliomyelitis, caused by poliovirus that enters water through the feces of infected individual and campylobacteriosis, which results from drinking water contaminated with feces. [23] These illnesses are more highly associated with women as well, because of the local practice of washing clothes in infested lake water.[24] The WHO studies state that 4% of all global disease burdens could directly be prevented by clean sanitation. [25] The number greatly increases with the inclusion of transmittable diseases from human beings and infectious diseases from animals and tools: for example, sterilized surgical instruments would prevent 40% of maternal death.[26][27]

On the bright side, several organizations are starting to focus on water scarcity in sub-Saharan Africa. Water Sanitation and Hygiene (WASH) is actively implementing projects in Kitui, Kenya, such as building giant wells, pipeline extensions, rainwater tanks and latrines.[28] Nestle initiated The Water for Education (WET) program to educating primary school students on washing hands and using latrines, and already visited 25 Nigerian schools in 2013.[29] A successful water project took place in 2013 in Mathibela, South Africa, where 24 households received access to fresh water from taps installed in their own yards.[30] Another exciting prospective project is for the Engineers Without Borders (EWB) in Louisiana to build water distribution infrastructures such as solar-powered water pumping systems, deep wells and easy-access fountains that will reach out to Sam M’Bollet, a small agrarian community in Gambia.[31]

Water use has been growing at more than twice the rate of population increase in the 21st century, yet certain regions of the globe, due to geographical and socio-economic reasons, are getting dehydrated.[32] Mabuya, a community member of Mathibela, said: “Some of us are sick but [are] forced to drink polluted water. We are happy because now… the government is doing something to meet our needs.”[33] This seemingly ordinary statement is in fact discomforting. Safe water should not be a “privilege,” especially when the “more-privileged” people are consuming it with no appreciation. Every hour, 115 Africans are dying from water-borne diseases. [34] To decrease this number, scientists must be more diligent in recording data, policymakers must quickly pass relevant laws, governments must invest towards development, and engineers must design effective infrastructures. Most importantly, the United Nations must concentrate on Target 7C to protect the most basic human right — the right to fresh drinking water and sanitation — with no discrimination against poor or rural citizens.

[1] United Nations Millennium Development Goals. (n.d.). Retrieved September 19, 2014, from http://www.un.org/millenniumgoals/bkgd.shtml

[2] 6 Ensure environmental sustainability. (n.d.). Retrieved September 19, 2014, from http://www.undp.org/content/undp/en/home/mdgoverview/mdg_goals/mdg7/

[3] WHO/UNICEF highlight need to further reduce gaps in access to improved drinking water and sanitation. (2014, May 8). Retrieved September 19, 2014, from http://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/notes/2014/jmp-report/en/

[4] Millennium Development Goal drinking water target met. (2012, March 6). Retrieved September 19, 2014, from http://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/releases/2012/drinking_water_20120306/en/

[5] Knudsen, D. (2014, September 15). Africa: Water Security No Longer a ‘Future Threat’ for Sahelian Africa. Retrieved September 19, 2014, from http://allafrica.com/stories/201409152614.html

[6] Knudsen, D. (2014, September 15). Africa: Water Security No Longer a ‘Future Threat’ for Sahelian Africa. Retrieved September 19, 2014, from http://allafrica.com/stories/201409152614.html

[7] Abutu, A. (2014, September 17). Africa: Access to Water for All Requires Government Investment – Taal. Retrieved September 24, 2014, from http://allafrica.com/stories/201409170748.html

[8] WHO/UNICEF highlight need to further reduce gaps in access to improved drinking water and sanitation. (2014, May 8). Retrieved September 19, 2014, from http://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/notes/2014/jmp-report/en/

[9] A Snapshot of Drinking Water and Sanitation in Africa. (2012). Progress on Drinking Water and Sanitation, 2012 Update, 5-7. Retrieved September 19, 2014, from http://www.wssinfo.org/fileadmin/user_upload/resources/Africa-AMCOW-Snapshot-2012-English-Final.pdf

[10] Ibid.

[11] The Millennium Development Goals Report 2012. (2012). 53. Retrieved September 19, 2014, from http://www.un.org/millenniumgoals/pdf/MDG Report 2012.pdf

[12] Kelty, B. (2014, September 17). Swimming for Water. Retrieved September 24, 2014, from http://www.huffingtonpost.com/bob-kelty/swimming-for-water_b_5836576.html

[13] Khosla, P., & Pearl, R. (2003). Untapped Connections. Retrieved September 28, 2014, from http://www.wedo.org/wp-content/uploads/untapped_eng.pdf

[14] WHO/UNICEF highlight need to further reduce gaps in access to improved drinking water and sanitation. (2014, May 8). Retrieved September 19, 2014, from http://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/notes/2014/jmp-report/en/

[16] Millennium Development Goal drinking water target met. (2012, March 6). Retrieved September 19, 2014, from http://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/releases/2012/drinking_water_20120306/en/

[17] WHO/UNICEF highlight need to further reduce gaps in access to improved drinking water and sanitation. (2014, May 8). Retrieved September 19, 2014, from http://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/notes/2014/jmp-report/en/

[18] A Snapshot of Drinking Water and Sanitation in Africa. (2012). Progress on Drinking Water and Sanitation, 2012 Update, 5-7. Retrieved September 19, 2014, from http://www.wssinfo.org/fileadmin/user_upload/resources/Africa-AMCOW-Snapshot-2012-English-Final.pdf

[19] Khosla, P., & Pearl, R. (2003). Untapped Connections. Retrieved September 28, 2014, from http://www.wedo.org/wp-content/uploads/untapped_eng.pdf

[20] Abutu, A. (2014, September 17). Africa: Access to Water for All Requires Government Investment – Taal. Retrieved September 24, 2014, from http://allafrica.com/stories/201409170748.html

[21] Pruss-Ustun, A. (2014). Burden of disease from inadequate water, sanitation and hygiene in low- and middle-income settings: A retrospective analysis of data from 145 countries. Tropical Medicine & International Health, 19(8), 894-905. Retrieved September 19, 2014, from http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/enhanced/doi/10.1111/tmi.12329/

[22] Water-related diseases. (n.d.). Retrieved September 19, 2014, from http://www.who.int/water_sanitation_health/diseases/en/

[24] Khosla, P., & Pearl, R. (2003). Untapped Connections. Retrieved September 28, 2014, from http://www.wedo.org/wp-content/uploads/untapped_eng.pdf

[25] Facts and figures on water quality and health. (n.d.). Retrieved September 19, 2014.

[26] Kelty, B. (2014, September 17). Swimming for Water. Retrieved September 19, 2014, from http://www.huffingtonpost.com/bob-kelty/swimming-for-water_b_5836576.html

[27] Anders Lanzen via Flickr

[28] Ibid.

[29] Nestlé tackling water issues in Central, West Africa. (2014, September 5). Retrieved September 19, 2014, from http://businessdayonline.com/2014/09/nestle-tackling-water-issues-in-central-west-africa/#.VCNQuNwXzwK

[30] Khumalo, G. (2014, September 13). South Africa: Mathibela Water Project Makes Life Easier for Villagers. Retrieved September 19, 2014, from http://allafrica.com/stories/201409140125.html

[31] Beal, K. (2014, August 25). Louisiana Engineers Without Borders help bring clean water to Africa | KATC.com | Acadiana-Lafayette, Louisiana. Retrieved September 19, 2014, from http://www.katc.com/news/louisiana-engineers-without-borders-help-bring-clean-water-to-africa/

[32] Scarcity, Decade, Water for Life, 2015, UN-Water, United Nations, MDG, water, sanitation, financing, gender, IWRM, Human right, transboundary, cities, quality, food security. (n.d.). Retrieved September 19, 2014, from http://www.un.org/waterforlifedecade/scarcity.shtml

[33] Khumalo, G. (2014, September 13). South Africa: Mathibela Water Project Makes Life Easier for Villagers. Retrieved September 19, 2014, from http://allafrica.com/stories/201409140125.html

[34] Scarcity, Decade, Water for Life, 2015, UN-Water, United Nations, MDG, water, sanitation, financing, gender, IWRM, Human right, transboundary, cities, quality, food security. (n.d.). Retrieved September 19, 2014, from http://www.un.org/waterforlifedecade/scarcity.shtml