Editor’s Desk: We are Mir

Branded a CIA agent by the Taliban, and a Taliban sympathizer by his critics, Hamid Mir is the face of political journalism in Pakistan. Listeners across the country tune into his talk show CapitalTalk on Geo News, one of Pakistan’s two private news broadcasters, to hear his latest segment on the military nation’s political climate. Besides interviewing world leaders, activists and terrorist masterminds, one of Mir’s primary focuses is unraveling the nation’s invisible hand – the Pakistani military.

Pakistan is not a state with an army; it’s an army with a state. Following the sunset of the British Empire, Pakistan was originally founded as a ‘Westminister-esque’ parliamentary democracy but has spent almost half of its existence under military rule. Over the years, Pakistan’s military dictators have executed elected statesmen, sanctioned mass murder against their own people, developed nuclear warheads from stolen schematics, and bankrolled regional insurgency movements with complete impunity. Following the hilariously bizarre 2016 ‘Fontgate’ scandal, where Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif was removed from power for the third time, the military – yet again – seems to be losing patience with civilian rule.

This past March, Geo News reported on Army Chief of Staff Gen. Bajwa’s apparent plans to abolish the 18th Amendment of the Pakistani constitution – the judicial gatekeeper against another coup d’état. Signed into law in 2010, the amendment was a paradigm shift in Pakistani civic-military relations as it severely limited the powers of the President – a position held as many times by major generals as elected officials – by revoking its ability to dissolve parliament at will, unilaterally declare emergency rule, and appoint the head of the Election Commission. Yes, for over sixty years, the President was able to choose who counted the votes.

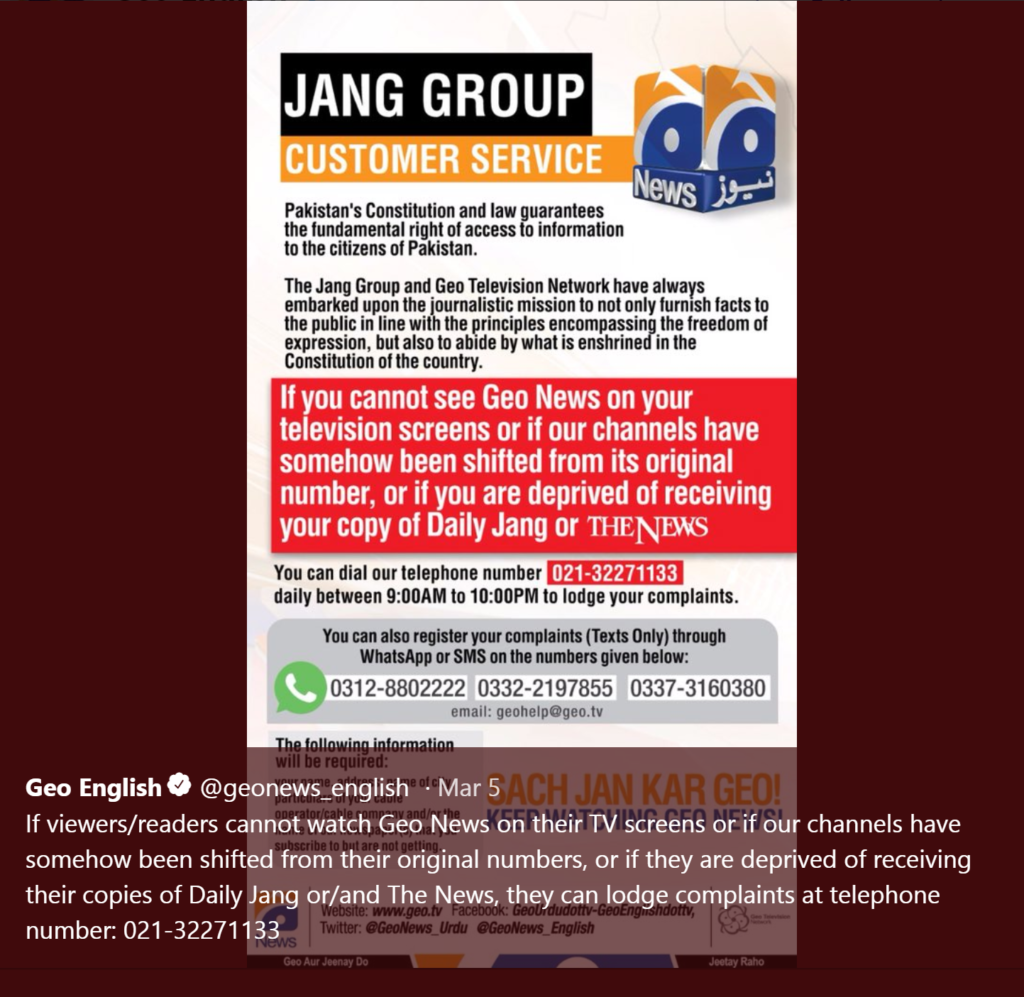

Shortly after its report, Geo News broadcasts suddenly went dark. To Pakistanis, however, this isn’t anything new. It’s an open secret that the Pakistani deep state has an itchy trigger-finger when it comes to independent journalism. Pakistan’s media censorship agency, the Pakistan Electronic Media Regulatory Authority (PERMA), exists to control the nation’s narrative and has cut Geo’s cord numerous times before, with the last instance in 2014 after the channel accused the Inter-Services Intelligence – Pakistan’s omniscient secret service – of attempting to assassinate Geo frontman Hamid Mir.

What was the national media’s response to the Geo blackout? Deafening silence. The story only gained international coverage after widespread condemnation on social media, as not a single local broadcaster covered the blackout. In an interview with Al-Jazeera, Executive Director of ‘Media Matters for Pakistan’ Asad Baig said, “We don’t expect any of these [media] rivals to be reporting on Geo’s shutdown. Why would they? It’s good for business…it’s as simple as that.” While Geo did eventually come back to life, it remains to be seen whether this is a pure reincarnation or a necromantic reanimation.

While journalists can cover most stories, there are certain organizations, and people, that they can’t touch. After all, Pakistan has one of the highest journalist mortality rates and lowest press freedom levels in the ‘democratic’ world. Many have been forced to flee the country in fear of harassment, abduction, or in many cases, assassination. Since 1992, 90 journalists and media workers have been killed. The troubled Baluchistan region is nicknamed the ‘Cemetery for Journalists’. The Committee for Journalist Protection named Pakistan one of the worst places to be a journalist and Freedom House bluntly categorized Pakistani media as ‘Not Free’. Need I keep going?

Having written for a yellow press in the Middle East before coming to McGill, censorship is something that I’ve experienced firsthand. I’ve had pitches shot down based on the pretense that they weren’t ‘patriotic’ enough, heard horror stories where writers were deported because of ‘controversial’ word choice making it to print, and witnessed the inner workings of state-sponsored journalism – an oxymoron if I ever saw one. In many ways, it was an educational and enlightening experience, but as soon as I received my Canadian study permit, I left the newspaper.

By the third day after moving into my dorm, I joined MIR. It was the only publication on campus, which I knew of at the time, that covered international affairs. What made me fall in love with MIR was the fact that it prioritizes its writers’ voices and maintains their articles’ integrity over everything else. It gives them the freedom to cover whatever they feel is important. Want to highlight an issue in your hometown? Yes, please. Write an open letter to the U.S. President? Go right ahead. Apply political theory to superhero movies? Why not! Born into the age of information, our generation is the most cognizant and critical generation to date, and here at MIR, we want to give them the spotlight.

For the past three years, MIR has let me cover topics in terrorism, militarism, and Islamism. Back where I’m from, these are subjects that nobody dares to write about, let alone talk about – just look at what happened to Geo. On the other hand, even here in the West, while there is coverage, it’s usually choreographed to suit some higher political power’s narrative – whether it be the double standards of terrorism coverage, the glamorization of the military, or the demonization of political Islam. That’s why student publications, which don’t have any political or corporate conflicts of interest, are so important. They don’t take orders from military dictators or pocket kickbacks from Super PACs. They exist to give our generation a platform to lend its voice to conversations previously reserved for the old guard.

University is a formative experience. It’s the time when we’re given the chance to express our passions, realize our talents, and figure out what professional path we’re going to take. As such, I believe it’s the duty of all student publications to act as that professional conduit, especially on campuses like McGill that don’t offer a journalism program. For the coming year, MIR will help fill that gap. With an increased focus on cultivating our writers’ talents, our primary goal is to make sure that every staff member that joins us, whether they stay with us for a semester or their entire McGill career, leaves a better writer and critical thinker.

Born with a passport from a garrison state that targets journalists like Hamid Mir and shuts down alternative publications like Geo, and having grown up in an oasis ‘paradise’ where the press glitters the ugly face of reality, MIR showed me what real press freedom looks like. It gave me, and countless others, the outlet to express ourselves on issues on the international stage. So, to every McGill student – whether you’re from the West, East, North, or South – join us, as we write with complete impunity.

We are The McGill International Review.

-Sarie Khalid, Editor-in-Chief