The Journalist’s Dilemma: Game Theorizing Terror Journalism (Part 1 of 2)

Via Google Creative Commons

Via Google Creative Commons

This article is the beginning of a two part collaborative series on the journalism of terror. Part Two will be published next week by Bella Shraiman.

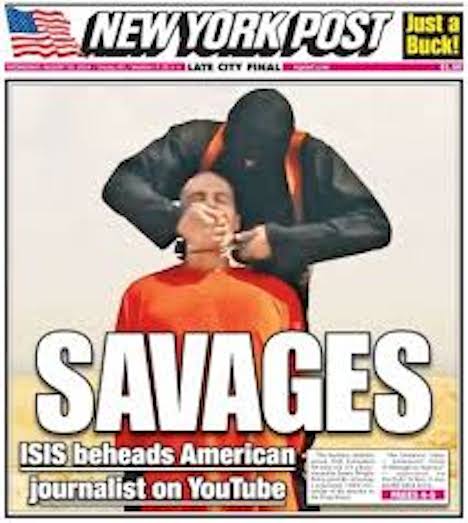

This past year has seen the rise of the Islamic State, an Islamist anti-systemic establishment, and with it the release of many beheading videos. Also known as ISIS, ISIL or Da’ish, IS is a “terrorist organization” – keeping in mind that the meaning of terrorist is widely disputed today – whose manifesto includes bringing back the caliphate. Because IS sees anyone who does not subscribe to their particular ideology as an enemy, their target is quite extensive and they have been able to showcase executions of individuals from many nationalities and religions, including aid workers and Syrian army men. IS has been releasing videos of the killings they perpetrate. Picked up by most news outlets around the world, their activities have hence recently risen to the forefront of the media, including both public and private broadcasting as well as the web.

Following a classification of terrorist tactics among 1) coercion, 2) provocation, 3) spoiling and 4) outbidding, IS’s strategy is most feasibly likened to the fourth option. Indeed, outbidding is useful when a terrorist group is trying to assert supremacy over other groups present in their area of attempted control.[1] By carrying out acts as horrific as beheading innocent civilians in the name of their cause, IS is trying to demonstrate its leadership and commitment, possibly relative to groups such as Al-Qaeda or even the state institutions present in the region. For instance, IS has recently captured part of a Syrian military airport, marking its rejection of the Syrian military establishment. In this context, the videos of the beheadings are significant because they help the group export its ideology and advertise the lengths to which it is willing to commit.

Terrorists thrive off of attention. Because they are non-state actors, they need to find other ways than brute force to try and win the conflict with states.[2] Part of this rests on the ability to recruit large numbers of followers so as to pervert national and regional institutions. Spreading their message therefore strongly benefits IS. However, they cannot do this alone and the media has been its loyal participant thus far in the struggle. Assuming that one of the most efficient ways for IS to signal its commitment to its principles is to prove its willingness to kill civilians, release and discussion of beheading videos is thus incredibly helpful to their cause.

The question is hence why. Why is the media complicit in IS’s strategy of reaching out to a larger, international audience, to advertise its dogma? Why would it choose to help terrorists accomplish their goals when it has the power to block it out, thus lessening the threat posed to the world system? The answer lies in one of the main tenants of international relations: Game Theory. Specifically, by taking the Prisoner’s Dilemma and molding it into a Journalist’s Dilemma, one can extract a rationale for the release and discussion of those videos to the greater public.

This article imagines that discussing the video of a beheading is similar to airing the video itself in the way it provides terrorists with the attention they seek. When IS releases a video, a network hence has a decision to make. It can choose to broadcast it, or it can choose not to. Assuming for the sake of simplicity that there are only two competing networks, the following 2×2 decision model can be derived:

| Network Y Network X |

Releases | Doesn’t Release |

| Releases | Outcome A | Outcome B1 |

| Doesn’t Release | Outcome B2 | Ouctome C |

Outcome A: Both networks release the video, the terrorists get what they want as their message gets spread out.

Outcome B1: Network Y doesn’t release the video, they are hurt by the loss of audience caused by the shift to Network X since they released the video. The terrorists get what they want although to a less-than-optimal extent since their message is likely to reach a smaller audience.

Outcome B2: Network X doesn’t release the video, they are hurt by the loss of audience caused by the shift to Network Y since they released the video. The terrorists get what they want although to a less-than-optimal extent since their message is likely to reach a smaller audience.

Outcome C: Neither of the networks release the video. The terrorists do not get what they want, and their message doesn’t reach a significant audience.

Networks are fueled by contradicting desires. On the one hand, as rational actors, they want to fulfill their job and reap the largest audience share possible relative to other networks. On the other hand, as citizens of civilized societies under attack from IS, they don’t want to help the terrorists achieve their goals. However, they see an individual journalistic victory as a bigger win than participation in a common effort to blackout terror ideologies. Thus, the following orders of preferences can be derived:

Network X: Outcome B1 > Outcome C > Outcome A > Outcome B2

Network Y: Outcome B2 > Outcome C > Outcome A > Outcome B1.

In this situation, there exists no credible way for a network to commit to not releasing the video. Thus, each network will expect the other to release it, and will choose to release it as well so as not to be competed out of the business. This leads equilibrium point A to be stable. In other words, the video gets released by both networks and the terrorists obtain their optimal outcome.

Intuitively, there seems a quite obvious solution to this dilemma: creating a credible commitment allowing the two networks to collude and not release the video. The easiest way to do this would be for states to enforce legislation banning the release of such videos. Unfortunately, this would go against two of the most cherished freedoms that society has managed to secure – in certain parts of the world – in the past several centuries: the freedoms of speech and of the press. Still, governments could build incentive packages to deter networks from making terror journalism their main sensationalist platform. Similarly, state-released statements appraising the population of the situation would take away from the media’s monopoly of information in this sector. Either way, there are possible mechanisms to prevent Equilibrium A and work against terrorism.

Unfortunately, this conceptualization of the Journalist’ Dilemma models the behaviour of two private networks. It can however also be successfully applied to other situations, for example public versus private, or public and private versus web media outlets. In this case, the possibilities of enforcing credible commitments are severely impacted. Furthermore, it is necessary to remember that, as models go, the vision of reality presented here is highly simplified. Thus, any potential solutions would need contextual input. To see how this plays out and to get more information on how to possibly avoid an equilibrium detrimental to the fight on terror, look out for Part 2 of this article which will come out next week.

To be continued…

[1] Frieden, Jeffry A., Lake, David A., and Schultz, Kenneth A. 2010. World Politics: Interests, Interactions, Institutions. (W.W. Norton & Company: USA): 393, 397.

[2] Ibid, 384.

Featured Image: Taken from Axis of Logic