Franco-phony: Assimilation in the 2018 Québec election

In both Canada and France, assimilation has long been considered an intrinsic part of immigration. It is considered easier for immigrants to adapt to the preexisting cultural norms of their new homes than for the host culture to adapt in any important respect. In Québec specifically, this can be attributed to a series of social movements hell-bent on preserving francophone québecois culture in the face of a vast and populous anglophone country.

Of course, extreme assimilation has a dark side. It would be irresponsible to overlook the fact that forced and coercive assimilation, largely in the form of residential schools, contributed towards cultural genocide carried out against indigenous populations. Though the majority of residential schools did not exist within Québec, the overarching purpose they were meant to fulfill— in short, to destroy indigenous culture and populations— very much did. Whatever the means, the results of coercive assimilation for the purposes of colonialism are nothing but horrific, and the fallout is still being felt keenly by a number of populations.

Recently, opinions regarding assimilation have mutated. Instances of state-sponsored coercive assimilation in the tradition of residential schools have become less frequent but the onus is still on immigrants, not just indigenous populations, to change. On the topic of contemporary assimilation and cultural agency, it is essential to consider the context of arguments presented. For a rather salient example, look no further than the recent controversy in the wake of France’s 2018 FIFA World Cup victory. The majority of players on the winning French national team were of African descent, which prompted many jokes to the effect that “Africa won the cup.” These jokes became the basis of a controversy over what truly defined a Frenchman, and the importance of cultural or ethnic heritage. In this case, the context was extremely important because both neo-nazis and people of African descent were pointing to the players’ race and backgrounds in order to make very different points. People calling the players completely French were also divided on a number of points, namely the importance of immigrants’ ethnic background to their cultural identity, a topic which has caused similar controversy across the Atlantic in Canada.

.jpg)

Maxime Bernier, People’s Party leader, Member of Parliament, and former Conservative is well known for railing against what he calls “extreme multiculturalism” that he believes is to the detriment of Canada. His claims that multiculturalism will divide Canadians into “tribes,” thereby destroying Canadian culture as it currently exists, are obvious dog whistles that stand as evidence of how truly divisive demanding extreme assimilation can be. While there is something to be said for national unity, it can be incredibly harmful to divorce people from their cultures. Furthermore, if a group is made to feel unwelcome or uncomfortable in a society, it stands to reason that they will not stay there, and Québec already has a problem with people leaving the province after living there for only a few years.

But ask the average Québecois politician and you will get the impression that these occurrences of cultural gatekeeping, such as the unequal application of secularism are characteristics of a bygone time— they couldn’t possibly touch the modern, secular, antiseptic society we live in today— but they do.

One of the most striking examples of the cognitive dissonance within Quebecois and French society when it comes to assimilation is the unequal application of secularism. In both Québec and France, the government, as well as all state-run institutions, must adhere to the tenets of secularism in accordance with the law. Last year, the Québecois “burqa ban” was instituted supposedly to ensure that anyone wearing a face covering would have to remove it in order to access government services. This policy actively target a disproportionately small percentage of the population; though estimates vary, the number of women wearing the burqa in Québec most likely clocks in between 10 and 100. However, in 2017 as well, in a rather overt display of what could be at best cognitive dissonance, and at worst active government prejudice, it was decided that the crucifix hanging in the National Assembly should remain there.

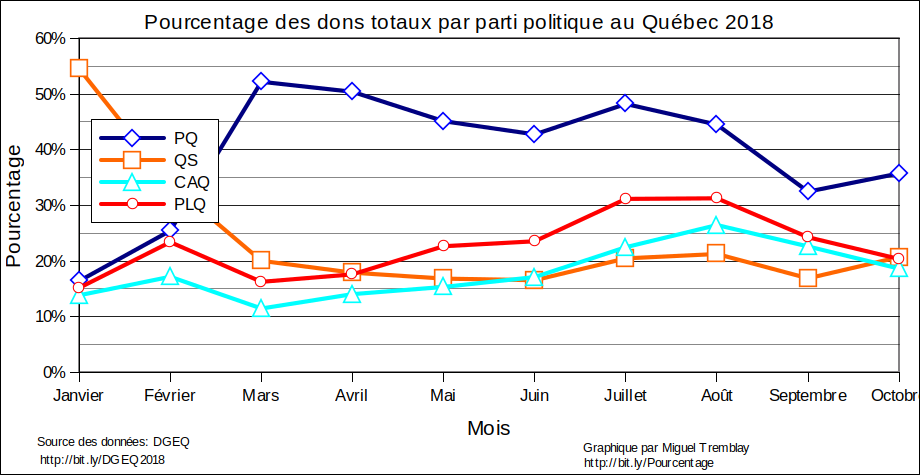

The effect of rising populism on the conception of culture within Québecois society is a particularly apropos topic for this election season. This election campaign has revolved around questions of culture, immigration, and regional power in a major way, and each party has approached these topics uniquely. François Legault, head of the Coalition Avenir Québec (CAQ) who enjoyed early success in the campaign took a particularly hardline stance on the subjects of immigration and the wearing of religious symbols. Though the CAQ was considered an early frontrunner, at times predicted to win the election, their chances are no longer as strong. This could potentially be due to the party’s continued emphasis on their populist opinions and hardline anti-immigration stance. In contrast, the Liberal Party and Québec Solidaire have pulled back significantly on anti-immigration sentiment, and have taken the opportunity to criticize the CAQ. Québec Solidaire specifically has worked to appear less populist than the CAQ, despite their strong ties to extreme nationalist group Option Nationale.

Quebec has a long history of diversity. At no point has Québec been entirely white, Catholic and French-speaking, which is a factor that seems to be often overlooked. Diversity is just as much a part of Québec history and culture as “de souche” culture; if it were celebrated equally, Québec would doubtlessly be a more attractive place for immigrants.

This should be a particularly attractive idea for any and all parties interested in Québecois independence. As it currently stands, Québec is not unequivocally leading Canada. The province already depends on the federal government for billions of dollars yearly, without the added expenses that independence would entail. During a debate earlier this month, Francois Legault announced that he intended to get rid of equalization payments, though it is not clear how he intends to accomplish this. However, were Quebec to become a leading province (through an influx of people and capital) to the point that politicians could realistically claim that the rest of Canada was holding Québec back, and if they could do it in a way that does not severely alienate crucial minorities, they could have a real chance of achieving their nationalist goals.

As easy as it is to think “if you’re coming here you should be ready to integrate completely into our society and if not, go somewhere else” the reality is not that simple. In 2018, rare is the western country that does not have a worsening population problem in terms of a low birthrate, and Québec and France are no exceptions. For generations, an elevated birth rate within the White Francophone community kept Quebecois culture strong. This is no longer the case. Governments do not hold all the cards in this exchange, and if political actors are not prepared to accept some basic shifts to their cultural makeup, then they are doomed to watch their societies slowly disintegrate into prejudice, xenophobia, and also poverty.

Edited by Andrew Figueiredo