Why Manila’s English-Speaking Bubble Needs to Pop

I’ve grown up speaking Filipino, and I don’t regret it. While my parents made sure that I became fluent in English, which I am thankful for, I spoke to everyone in my house in Filipino. Up until the ninth grade, I went to school in Manila, where I studied Filipino. Even after I left the country, I still use the language every day with my family and Filipino friends, so you can imagine my confusion when I was asked “do you still speak Filipino?” when I returned home.

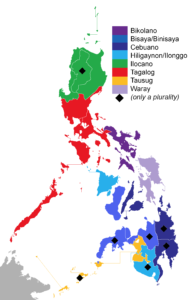

Last summer, I visited Manila for the first time since I left in 2014. I expected to be shocked by how much more traffic there would be (which there was), but the real surprise came when I encountered some kids who only spoke English fluently; their ability to speak Filipino was comparable to those who learned it as a second language. I even spoke to a kid who couldn’t count to ten in Filipino—something I have managed to teach my non-Filipino friends. At best, I was able to speak to these kids in Taglish – a hybrid of Filipino and English. I realized that my fluency was previously questioned because there are young people who, despite having parents who speak Filipino, do not speak the language fluently. I can see how this could be in other parts of the country, as there are 184 languages spoken throughout the 7,641 islands, but not in Manila, the capital, where I grew up with the norm that one must speak both Filipino and English fluently.

Filipino kids grow up learning English, as the national curriculum requires English classes starting the first grade. By the fourth grade, the language of instruction begins to transition from mother tongue-based to English and Filipino, and in private schools, there is a greater focus on teaching in English. The most prestigious universities in the country may require some Filipino electives, but classes are predominantly in English. Because of this, English fluency is seen as a measure of intelligence. With this in mind, it is understandable that parents encourage the use of English over Filipino. If their child is fluent in English, then it becomes easier to succeed in higher-level professions (medicine, law, business, etc.) that require proficiency in the language. However, in their focus to teach English, parents could have overlooked ensuring that their kids speak fluent Filipino.

It would be easy to blame these parents, but the problem is rooted much deeper than that. English proficiency defines a Filipino’s intelligence because of the culture established by American colonization. For almost 50 years, there was more importance placed upon English fluency than the local languages of the country. By the time the Philippines became independent in 1946, English was already ingrained in the education system, and fluency creates more opportunities. In order to succeed in this context, parents need to focus on English proficiency instead of Filipino. While this historical background explains the current environment, Filipinos must realize the issues that it brings; it doesn’t excuse the loss of their language. It’s important to know the consequences of creating a language divide because it could be the cause of the city’s downfall.

The majority of the English-speaking kids I encountered were those of the upper class. When I worked with kids from low-income families, they were more comfortable speaking to me in Filipino despite having a solid grasp of English. In the current context, their parents see English fluency as a way out of cyclical poverty, but it is difficult to provide the English-speaking environment their child needs for language immersion because they are not proficient enough themselves. When interacting with kids of higher economic standing, I spoke to them in English if I wanted them to understand me completely.

If there is a whole generation of upper-class citizens who can’t speak the local language, then it will cement the gap between rich and poor. There’s already quite a wealth disparity between the citizens of the Philippines, and a language barrier is the last step towards finalizing the divide. Once English is established as the sole mother tongue of a whole generation of Filipinos, the upper class will choose to only establish ties amongst themselves, as it will become difficult to communicate with the rest of their countrymen. The divide isn’t even far from the everyday reality of the rich; their house help (cleaners, cooks, etc.) are all from lower-income families who don’t have the advanced English instruction their employers had. Despite proximity to the issue, the rich aren’t motivated to address it because there doesn’t seem to be a need to. Furthermore, it will become almost impossible for poorer kids to rise out of poverty because they will never be able to compare with the native-level fluency of English the upper-class kids grew up with. Especially if the well-off continue to live in their bubble, those trying to break out of the cycle of poverty can only watch that bubble filled with opportunities float further away from them.

It can be possible that instead of the upper class improving their Filipino, everyone else in the capital would focus on learning English instead. This could be convenient because it is already deemed the dominant language of instruction. However, this would be a sad turn of events for the Filipino culture. I am not suggesting that it is also ideal to abandon fluency in English; it is the language of business in the country and the rest of world. Filipinos’ ability to speak English has granted many opportunities to advance in the global context, as there aren’t a lot of countries in Asia with so many people able to communicate so well in English. I am arguing that there needs to be a true bilingualism in all residents of the capital in order to avoid further divides between classes.

If the capital continues on this track, the economic divide will continue to grow. The future seems bleak, but it’s not too late to change things. On an individual level, Filipinos must realize that it is essential to speak their mother tongue on a regular basis in order to maintain fluency. It can seem inconvenient to go out of the way to use the language if one lives in an English-speaking bubble, but it’s not an impossible task to do. Filipinos believe in and live by the concept of bayanihan: a spirit of unity, cooperation, and empathy. This cannot be achieved if Filipinos can’t understand their fellow countrymen.

Edited by Sarie Khalid, Alec Regino, and John Weston