The Art of Pakistan’s Superpower Financial Finesse

Pakistan has historically relied on international institutions and superpowers to save itself from it's financial and security woes, but is this geo-economic model sustainable?

Prime Minister Imran Khan during his inauguration in August 2018

Prime Minister Imran Khan during his inauguration in August 2018

Pakistan has always been an enigma in international politics. The country has historically leveraged its geo-strategic location and vast military capabilities against global powers in exchange for financial and military aid. Even during the Cold War, when an iron curtain split the world in half, Pakistan managed to crook and crutch both the Soviet Union and the United States – while receiving financial aid from both sides and maintaining its own agency on the international stage.

Today, Pakistan is at a critical juncture in its short history: it finally experienced its first-ever transition of civilian power and is undergoing its worst-ever financial crisis. Pakistan’s grand strategy hasn’t changed under Prime Minister Imran Khan. He is already flirting with working with both Saudi Arabia and Iran; continues to play both sides on the ‘War on Terror’ and is morphing Pakistan into a Chinese economic-counterweight to India.

Lendee Of The Last Resort

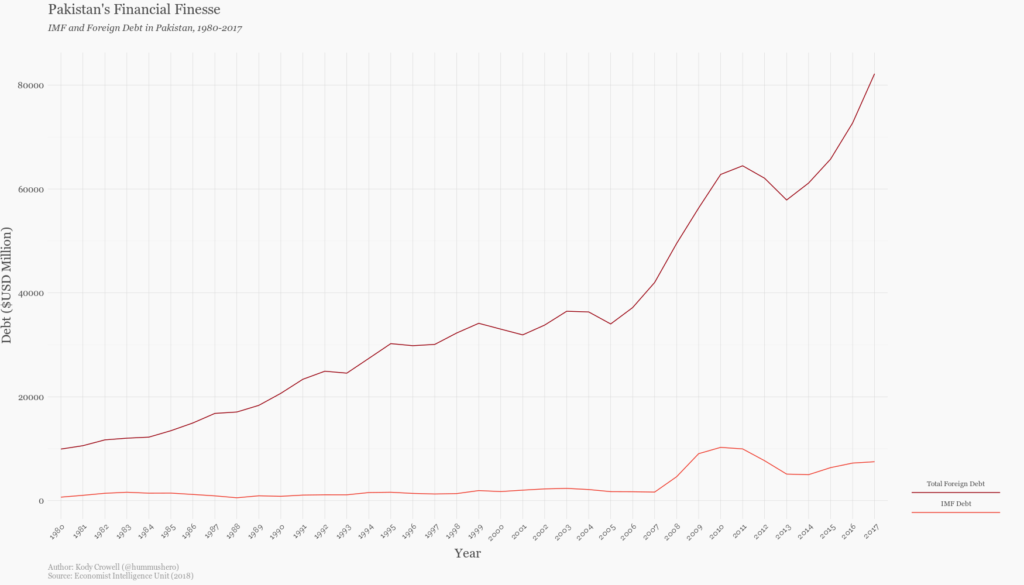

In August, Prime Minister Imran Khan inherited Pakistan’s worst financial crisis. Thanks to years of reckless international borrowing, over the past two years, Pakistan has gone from being Asia’s best performing market to one of its worst. Foreign debt is estimated at $84 billion, youth unemployment is at 7.7% and inflation rates have risen to 4%. The balance of trade is also running a $3.46 billion deficit and the Pakistani rupee is at a decade-record low at Rs 144 against the U.S. dollar.

By disregarding its civilian economy, Pakistan has overwhelmingly chosen guns over butter. The defense budget is currently allocated $6.8 billion and is predicted to surpass $8 billion in 2019. Military pension makes up 76% of the federal government’s pension bill. Pakistan is also the 9th largest arms importer and, between 2013 and 2017, purchased 2.8% of all weapons sold in the international arms market. While its military industrial complex is thriving, the Pakistani economy is reaching a breaking point and, without international aid, is destined to default.

In October, Khan requested a bailout package from the International Monetary Fund (IMF). Since the 1980s, Pakistan has received twelve IMF bailouts and has just requested its thirteenth – the largest bailout package yet worth up to $12 billion – to solve its economic calamities. Pakistan has historically failed to meet IMF loan conditions, such as trimming fiscal spending, and only managed to complete one IMF program in 2016. Pakistan has also been accused of pocketing international aid to sponsor terrorist groups like the Taliban and Lakshar-e-Taiba against neighboring rivals Afghanistan and India. Citing Pakistan’s ‘deliberate’ misuse of U.S financial aid and IMF funds, the Trump administration is fervently against another bailout. Given its abysmal CCC sovereign risk rating and harrowing foreign debt repayment rate, combined with Washington’s protests, Pakistan’s monetary luck may run out on its thirteenth try.

Saudi Arabia’s Closest Muslim Ally

Back in September, Imran Khan turned to his regional allies and took the first available flight to Saudi Arabia. Khan was desperate for a $4 billion economic bailout from the House of Saud. Despite Pakistan being one of the Saudis’ closest allies, Riyadh refused and Khan returned home empty handed.

By mid October, amid international criticism and diplomatic isolation following the Jamal Khashoggi assassination, the Kingdom invited Imran Khan to a one-day meeting with King Salman and Crown Prince Muhammad Bin Salman (MBS). The next day, he returned to Pakistan with $6 billion in his pocket – $2 billion more than initially requested. Having previously been rebuffed by the Kingdom, Pakistan is now assured a Saudi bailout package.

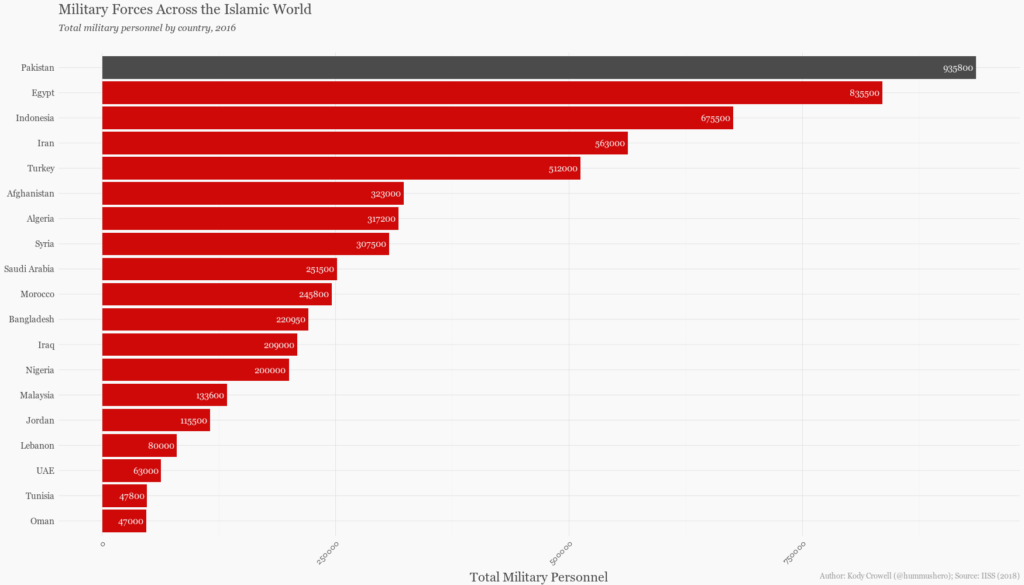

Traditionally, Saudi-Pakistani relations have centered around security, not finance. The Pakistani military has played a major role in supplying and training the Saudi armed forces. Since the 1980s, Pakistan has stationed entire military divisions in the Kingdom to deter foreign invasion and domestic terror. The ‘Islamic Military Counter Terrorism Coalition’, a pan-Sunni Islamic NATO founded and financed by Saudi Arabia, is also led by a retired Pakistani general.

While the House of Saud begrudgingly bailed out Pakistan, they happily invested $44 billion into a single oil refinery in India. Saudi investment into Pakistan’s religious establishment has empowered radical terrorist groups and hardliner political parties. Despite its close security ties with Islamabad, Riyadh hasn’t done much in the way of meaningful hard asset investment. The initial bailout refusal is a testament to the Saudis’ pessimistic evaluation of Pakistan’s credit risk.

Despite Riyadh’s recently lukewarm relationship with Islamabad, they cannot afford to lose Pakistan to its regional rivals. Realizing that they are not exclusively tied to Saudi Arabia, Pakistan has started to look towards Iran for diplomatic, economic, and military support. Pakistan has supported Iran’s right to become a nuclear state, increased bilateral trade and is currently working with Iranian security forces to quell the Baluchistan insurgency across their borders. In 2015, in what the Saudis saw as diplomatic heresy, Pakistan’s parliament – in a rare show of solidarity – unanimously voted against joining the Kingdom’s military coalition against the Iranian bankrolled Houthis in Yemen. Pakistan had sent a clear message to Saudi Arabia: this isn’t our war.

The Saudi financial injection isn’t the brainchild of compassionate reflection but of diplomatic pragmatism. The Khashoggi incident was a seismic shock to the Kingdom’s economic ambitions, diplomatic integrity and self-styled ‘progressive’ image. Since Pakistan has the largest military in the Islamic world and is the only Muslim nuclear state, Saudi Arabia needs Pakistan now more than ever.

Washington’s S.O.B

2018 started on the worst possible note for U.S-Pakistan relations. President Trump’s inaugural tweet accused Pakistan of misusing $33 billion in U.S aid since 2002 and claimed that Islamabad saw the White House as “fools” (which is probably true). For once, Trump followed up on his words by cutting all fiscal aid to Pakistan.

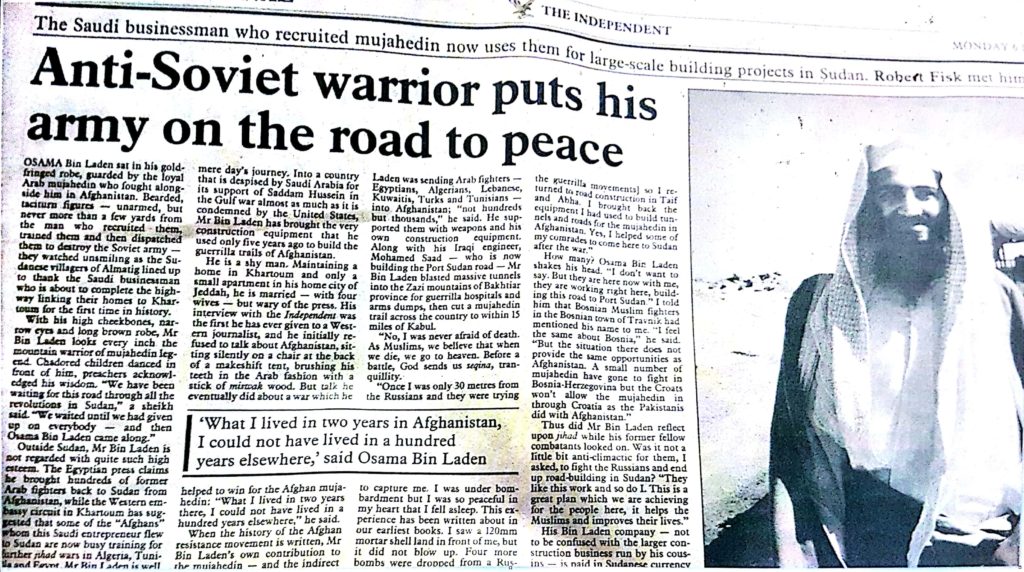

In 1939, U.S President Franklin Roosevelt reportedly remarked that Nicaragua’s Somaza Sr was “a S.O.B, but he’s our S.O.B.” Like Nicaragua under Somaza’s junta, Pakistan has historically enforced U.S foreign policy in exchange for financial aid and diplomatic tolerance. During the decade-long Afghan-Soviet war in the 1980s, Washington handed Islamabad $20 billion to mobilize and radicalize Afghan Mujahdeen fighters – who later midwifed the Afghan Taliban and Al-Qaeda – against the Soviets. Following the 9/11 attacks, the Bush administration called on Pakistan to join its ‘War on Terror.’ From 2002 to 2011, the White House pumped $11 billion into the Pakistani military to combat terrorism and another $6 billion for the Pakistani economy to endure it.

Then, on May 2nd 2011, U.S special forces assassinated Osama Bin Laden in his secret hideout in Pakistan – a stones throw away from the country’s premiere military academy. Fearing that the Pakistani military had been compromised by Al-Qaeda sympathizers, the Obama administration made the call without telling the Pakistanis. The day after Bin Laden’s assassination, Pakistani military personnel swarmed the compound to secure the premises, search its interiors, and inspect a downed Navy SEAL silent-helicopter. The Pakistanis didn’t scavenge the SEAL wreckage alone, alongside them were the Chinese.

To learn more about US-Pakistan relations in 2018, feel free to read my piece on the situation.

Secession hinders Success

In November, Khan traveled to China to discuss the future of the China–Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC). Unlike Washington and Riyadh, Beijing pro-actively seeks to enhance both security and commercial ties with Islamabad. Ever since Pakistan joined China’s ambitious Belt and Road project (B&R) as part of its flagship CPEC initiative in 2008, Sino-Pakistani geo-political interests have since intimately intertwined. China has promised $62 billion worth of foreign direct investment into Pakistan’s economy via free trade pacts, and development projects in order to solve its own economic, energy and security dilemmas. Pakistan has already started to prepare for the future by establishing special economic zones for Chinese firms, introducing Mandarin into its education system and circulating commemorative rupee coins engraved with the Pakistani and Chinese flags. Should all CPEC initiatives be implemented, the total value of these projects would exceed all foreign direct investment into Pakistan since 1970, and will be equal to 20% of Pakistan’s 2018 gross domestic product.

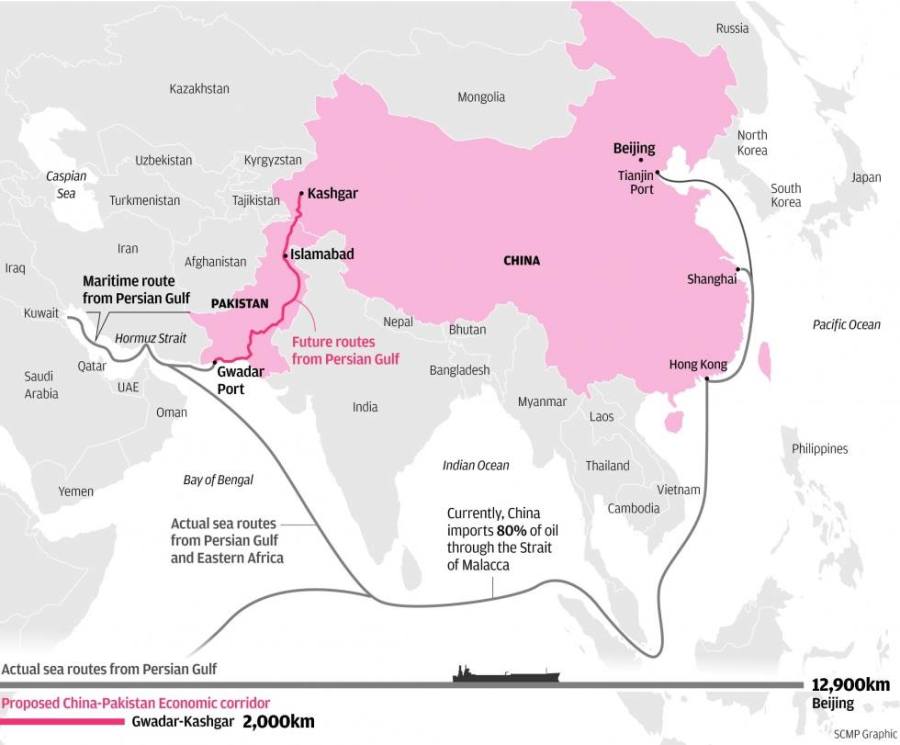

Last week, Saudi Arabia announced it will sign a five year plan to increase its total oil exports to China up to $1.67 million in barrels per day. Saudi oil transport to China has always been endangered by pirates, foreign power interception and choke-point blockades. The Politburo’s increased reliance on Saudi Arabia, and heightened tensions with India and the U.S, have forced them to re-evaluate their oil transport routes – that’s where Pakistan comes in.

Over a forty day long journey, oil tankers sailing to Beijing must cross the claustrophobic Straits of Hormuz, traverse the Indian Ocean’s navy patrolled seas, and then navigate through U.S naval-air bases stationed across the Strait of Malacca and South China Sea. Through CPEC, China avoids all these geo-strategic hurdles by transporting its Saudi oil imports directly through Pakistan – cutting delivery time from forty to ten days.

Based in Gwadar Port in Pakistan’s oil-rich Balochistan province, CPEC infrastructure development projects are expected to morph the tiny port city into an international energy hub. In order to increase bilateral land trade, cut Saudi oil delivery time, and eliminate tanker interception risk, CPEC promises to build power plants, railways and highways cutting through Pakistan into China from Gwadar Port to Kashgar in China’s Xinjiang province – the B&R initiative’s western link to the rest of Asia. However, secessionist movements in Xinjiang and Balochistan have thrown a wrench in Pakistan and China’s geo-economic ambitions.

In late November, soon after Imran Khan returned from China, the Balochistan Liberation Army (BLA) attacked the Chinese consulate in Karachi, Pakistan. The Balochistan insurgency crisis has intensified ever since CPEC was announced a decade ago. Alongside their on-going struggle for secession, the BLA have cited the lack of CPEC’s economic dividends to the struggling province. Gwadar Port no longer belongs to Balochistan as it has been handed over to the Chinese on a forty year lease. Balochi contractors and workers are not even involved in CPEC infrastructure projects. Even Balochistan Chief Minister Mir Bizenjo has stated that CPEC neglects Balochistan’s economic development in favor of Xinjiang.

The Uyghur, a minority group that is ethnically and culturally distinct from the rest of China, have campaigned for Xinjiang’s secession to form an independent state of their own. Moreover, Uyghur militant groups have threatened guerrilla attacks against CPEC project sites. In response, the Politburo is culturally-cleansing the entire Uyghur population. Thousands of Uyghurs are being forcibly transferred to ‘re-education’ camps, and they’re banned from professing their Islamic faith. So far, only Pakistan’s Religious Affairs Minister Noorul Qadri has condemned Beijing’s draconian policies, while Imran Khan and the military, despite their Islamist leanings, have chosen to look the other way.

Pakistan’s self-finessing prophecy

Pakistan’s great power geo-economic model isn’t sustainable. Saudi Arabia has already started to show financial favoritism towards India due to its growing share in the world economy and Pakistan’s imperishable economic woes. When Imran Khan first visited Saudi Arabia, his bailout proposal was shot down while Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi, on his first state visit, was greeted with open arms and received the prestigious Order of King Abdulaziz award. Islamabad’s growing relations with Tehran has also started to worry the Kingdom as they now look towards India for diplomatic, and economic cooperation.

The Trump administration’s financial aid embargo has already incapacitated the Pakistani economy. Also, due to the Pakistani military’s unreliability, the White House has successfully lobbied for Pakistan to be placed on the global Financial Action Task Force’s ‘grey’ list for state-sponsoring terrorism, putting the country at risk of international sanctions. The IMF and Washington have also questioned Pakistan’s financial integrity by requesting access to CPEC’s secretive agreement terms – which Pakistan refused to disclose. If US-Pakistani relations continue to deteriorate, the White House risks losing Pakistan’s alliegence to the Politburo.

CPEC isn’t going to plan as numerous CPEC infrastructure programs have been cancelled, and Chinese workers are routinely targeted by Balochi insurgents. Pakistan is also in danger of falling into a Chinese debt trap already faced by multiple African B&R clients. Pakistan already owes $19 billion to China, and CPEC loans will add another $11 billion to its $84 billion total foreign debt.

Prime Minister Khan has a laundry list of economic and foreign policy issues to address. The Pakistani military, which has never won a war, must cut its over-inflated defense budget and stop sponsoring proxy insurgencies against its neighbors. Islamabad must pick a side in the Saudi-Iranian cold war, or even better, avoid it completely. As long as the Balcohis aren’t involved in CPEC’s projects, unemployment in the province will persist and BLA guerrilla strikes will continue to hamper CPEC’s progress. If Imran Khan hopes to do what is best for Pakistan and its peoples’ interests, he must focus on refining the country’s economic framework and reduce Pakistan’s financial reliance on world powers or risk economic and geo-political catastrophe.

Edited by Pauline Werner

Special thanks to Kody Crowell, Gracie Webb and Danial Ahmed

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors’ and do not necessarily reflect the official position of The McGill International Review or IRSAM.inc