Two Cities, One Culture: The Aftermath of High-Profile U.S. Police Shootings

Three white Chicago police officers stood trial at the beginning of December in connection to the 2014 deadly police shooting of black teenager Laquan McDonald. Their colleague, Officer Jason Van Dyke, was convicted of second-degree murder in September, after he shot and killed McDonald during the confrontation. While Detective March and Officers Gaffney and Walsh fired no shots during the incident, they were later brought to trial on charges of “obstruction of justice, conspiracy, and official misconduct”: essentially, for the subsequent cover-up. The judge has since postponed her verdict until the new year.

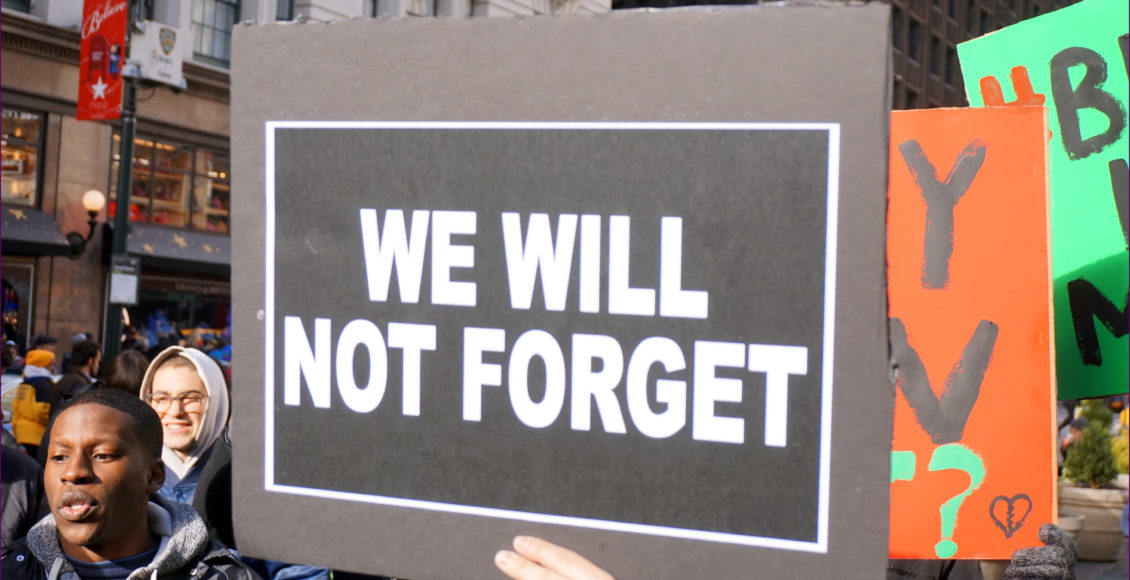

While the conviction of Officer Van Dyke is a step in the right direction, it does not acknowledge the epidemic. This trial of the cover-up is the first glimpse of an attack on the culture that allows these shootings to happen in the first place. The fallout within city police departments involved in shootings that garnered widespread public outrage—such as those of Laquan McDonald in Chicago and Freddie Gray in Baltimore—highlights much larger issues of the police culture within. While the #BlackLivesMatter protests might be less frequent or attract less coverage now, the nation is still waiting on reform.

Chicago: A Code of Silence

Amongst a public still reeling from the fatal shooting of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri just a couple of months earlier in 2014, the story of the 17-year-old McDonald being shot 16 times by a white officer went largely unremarked at the time. Initial reports told stories of a black male lunging at police officers with a knife, framing a killing with good reason. It took 13 months, 4 lawsuits, and a subpoena from a city judge for the police department to release the infamous dash-cam video. To culminate suspicion surrounding previously-confidential footage, the county prosecutor charged Officer Van Dyke with murder, mere hours before its release.

The fallout was very public. Protests swept the city, Mayor Rob Emanuel promptly fired the Chicago police superintendent, voters ousted the county prosecutor, and the U.S. Department of Justice initiated a formal investigation into the conduct of the city police department. Two damning realizations emerged in centre-view: Van Dyke’s unnecessary and excessive use of force in the incident, and the obvious attempts—through falsified reports and buried footage—to cover it up.

Chicago Police Department has long seen a pattern of police misconduct and unconstitutional use of force. Most infamous is its notorious “code of silence” used to cover up these instances (to use Mayor Emanuel’s own words). New surveillance footage showed all officers involved in the Laquan McDonald case met back at the police station to discuss the incident; subsequently, several of the officers’ reports featured suspiciously similar language. Even after the public fallout around the McDonald shooting, the code of silence in the Department continued: failure to report the dangerous alcoholism of an officer who caused a homicidal car crash in 2017; the cover-up of a civilian assault by an officer off-duty; and a total of $225 million was borrowed by the city for police settlements and trials in 2017 alone. Not to mention, a local whistleblower suit recently came to trial, where two Chicago officers claimed retaliation and severe harassment after they aided an FBI investigation into internal police misconduct.

Misconduct—in this case, discriminatory use of deadly force—and weak accountability systems go hand-in-hand. A continued code of silence means continued police abuse goes unreported. To dismantle this network of omertà within the Department, firing a few high-profile officers is evidently not enough.

Baltimore: The Legacy of Zero-Tolerance

In 2015, the country was hit with yet another city police killing that sparked public backlash. 25-year-old black American Freddie Gray was brutally arrested in Baltimore for possession of a switchblade, tased multiple times, shackled, and given a rough ride in the back of a police van with no seatbelt. He died later of severe bodily injuries, which included a severed spine. The six police officers involved were later charged, but acquitted of any federal crimes. While Baltimore’s case of Freddie Gray also centers on a code of silence —the “blue wall” of six officers blurring the lines of accountability—it also serves to highlight another long-term grievance: the legacy of “zero tolerance” policing.

The zero-tolerance policy followed by Baltimore law enforcement was a direct result of the crack epidemic and widespread African-American unemployment in the late 1980s. Tested in its infancy in New York, the policy was first implemented fully by Baltimore Mayor Martin O’Malley in the late-1990s to “clean up the city.” Essentially, zero-tolerance is drag-net policing: widespread arrests for petty, routine crimes. In a city that is 63 percent African-American, this community was undeniably hit the hardest. Black residents accounted for 84 percent of police stops, a large amount without any legitimate suspicion or cause. Many officers even made up reasons for unlawful arrests on the spot. High arrest-counts were awarded with promotions, only fueling the fire of unlawful stop-and-frisks. The damaging results were two-fold: large-scale alienation and distrust of police among the African-American community, and a decades-long habit of unconstitutional policing.

The fallout of the Freddie Gray case is particularly alarming because the backlash against zero-tolerance policing resulted in an immediate spike in the city’s crime rate. The Baltimore police could not police effectively once the drag-net policing stopped. They could police unconstitutionally, or not at all. Ten months after Freddie Gray was killed, another black teenager, LaVar Douglas, was shot by a police officer near a Baltimore college campus. The Department still has not released the name of the officer who killed him. In February 2018, a huge corruption scandal broke where Baltimore officers were accused of cheating and stealing from citizens, only furthering community mistrust. Racist, elitist, and distrustful policing continues in the city, rocking the chances of piecemeal reform.

The Culture

Chicago and Baltimore are not stand-alone cases so much as indicative pieces of a larger whole. The ACLU prescribes physical reforms, such as cameras, misconduct investigations, and civilian review boards to combat weak accountability systems. As in the cases of Chicago and Baltimore, federal and local investigations have only begun to expose the epidemic. Police body cameras have been implemented in both cities—as well as many more counties across the country—yet, the shootings continue.

The problem is clearly a cultural one. Superficial reforms treat the symptoms, but not the disease. Codes of silence and habits of unconstitutional policing continue to exist across the nation, with deeply ingrained effects. Bring the officers to court, fire some politicians, or prompt a DoJ investigation, but the culture of community distrust and dominant police power still remain.

On police reform, author Ta-Nahisi Coates writes in his book Between the World and Me: “You may have heard the talk of diversity, sensitivity training, and body cameras. These are all fine and applicable, but they understate the task and allow the citizens of this country to pretend that there is real distance between their own attitudes and those of the ones appointed to protect them.”

#BlackLivesMatter is not over. Evidently, a much larger task lies ahead.

Edited by Shirley Wang