What Explains the Rise of Vox in Spain?

In December 2018, the right-wing populist political party, Vox, won 12 parliamentary seats in the Andalusian regional election, thus entering a regional Parliament for the first time. Vox, founded in December 2013 by former members of the People’s Party (PP), hailed demands for a centralized government as opposed to the quasi-federal political system of ‘Autonomous States’, instituted in 1978, and vocalized a sturdy opposition to Catalan and Basque separatism as flagship policy concerns. Nonetheless, the traditional far-right views also permeate in Vox: anti-abortion, anti-same-sex marriage, anti mass-immigration, anti-Islam, criticism of multiculturalism, soft Euroscepticism, anti-feminist. In 2019, as it bargained for the formation of a coalition with the Partido Popular and Ciudadanos in Andalusia, it published a list of 19 demands, including the repeal of regional legislation providing special protection for LGBTI groups and women, the elimination of public subsidies for ‘supremacist feminism’, the deportation of 52,000 undocumented migrants, new laws protecting bullfighting and hunting, and cuts in regional self-government. So, what explains the emergence of the political party and its establishment in Spanish political dynamics? Why has Vox gathered such momentum?

The absence of right-wing populism

Until recently, political scientists were puzzled about Spain not succumbing to the mouth-watering temptations of far-right populism, despite high levels of unemployment which are traditionally a contributing factor. Two main hypotheses can explain the absence of a rising far-right:

- The proximate memory of Franco’s long-lasting dictatorship. Nonetheless, the exhumation of the dictator’s tomb debacle seemingly illustrates the fact that support for Franco is still alive and well. This is perhaps the consequence of the absence of ‘de-franco-isation’, comparable to ‘de-nazification’ in Germany after the Second World War. That said, the topic remains rather taboo.

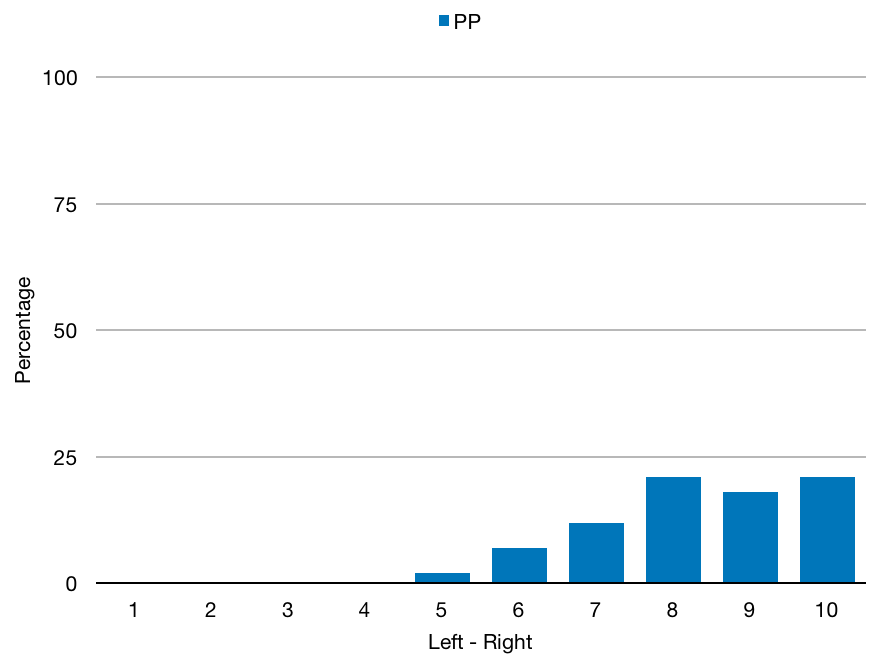

- The People’s Party, the traditional-right wing, was already sufficiently to the right on the political spectrum, which inhibited the creation of a strong far-right party. This hypothesis holds more validity, especially when considering the position of the PP according to CIS in 2015.

So, despite the PP’s strong tendency of defending ultraconservative values, why has Vox managed to establish itself?

The Position of Political Parties in Spain

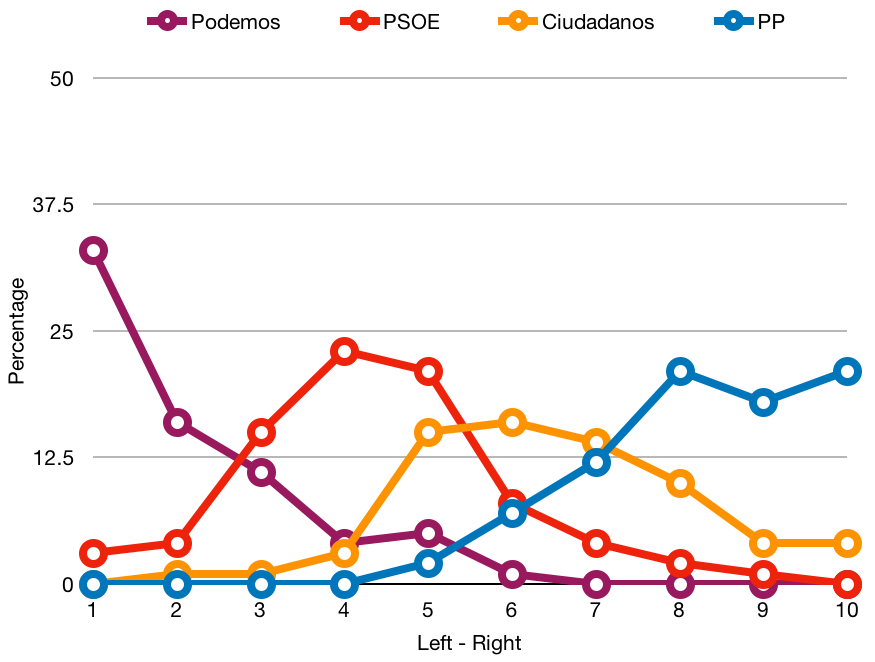

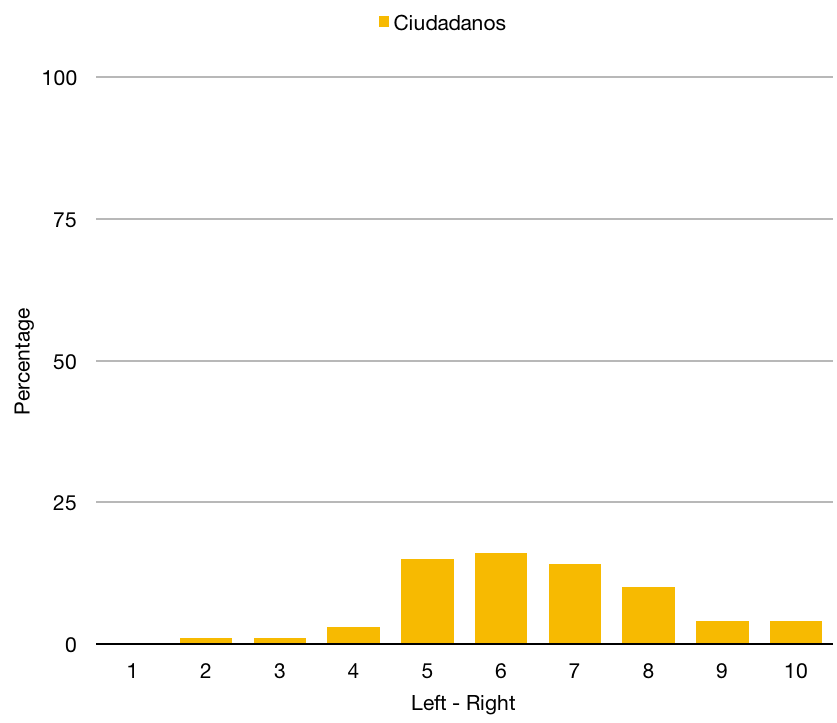

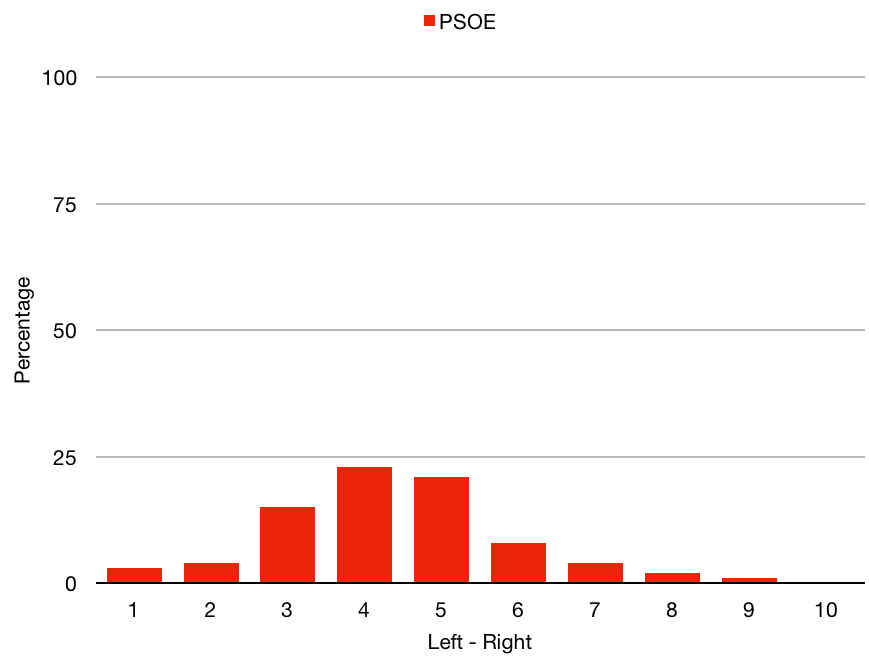

In 2015, after a daring declaration from the right-wing newspaper, el Mundo, suggesting that Albert Rivera, the president of Ciudadanos, ‘could be characterise as a centre-left leader’, the Huffington Post analyzed the position of Spanish political parties on a left-right spectrum. Based on CIS data, it revealed that many Spaniards consider Ciudadanos centre-right, thus explaining the debate occasioned.

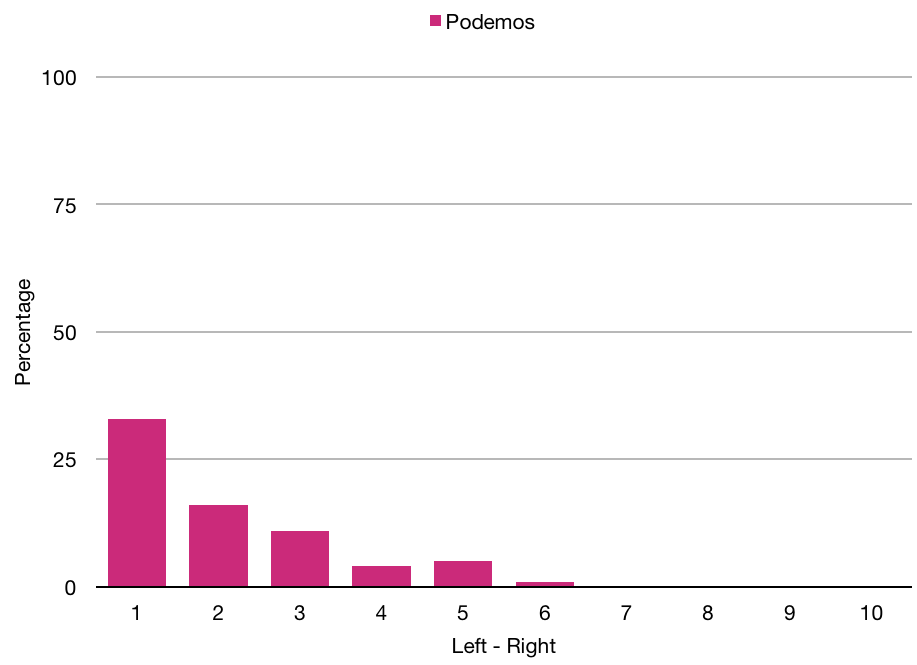

It also showed numerous spatial representations of all the main parties, since the end of bipartisanship: Podemos, PSOE, Ciudadanos and the PP.

The Huffington Post and CIS information dates from 2015. So, what about more recent developments?

The Shift of the Right

The Partido Popular’s support base was strongly eroded with the emergence of Ciudadanos. In 2015, the traditional right lost over 60 seats, compared to 2011. The centre-right party slowly surfaced in the Catalan regional election in 2006, as a vocal opponent of secession, and gained momentum in the 2015 general election, earning 40 seats in the Cortes Generales. In 2016, it lost eight seats, retrieved by the PP. The PP thus rose back from 123 seats to 137, but hardly achieving their 2011 level of 186 seats.

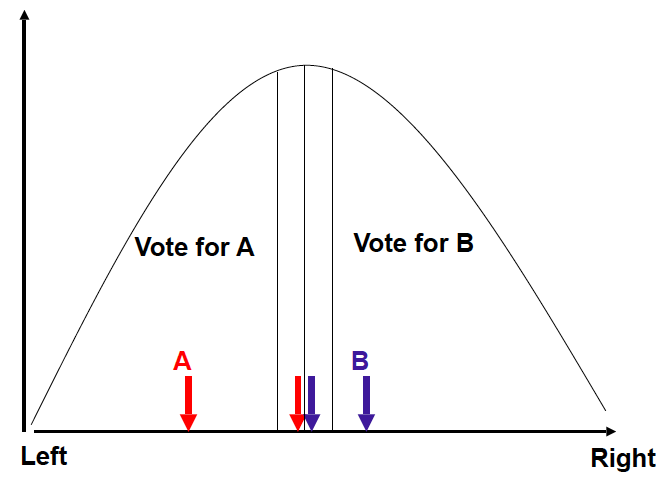

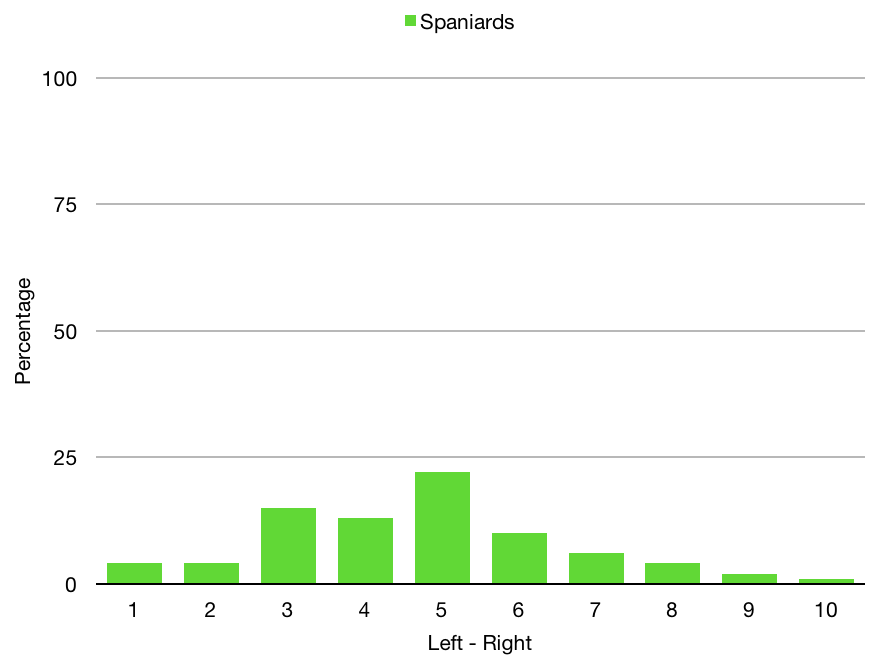

This hypothesis is sustained by the CIS data that shows a bell curve of a majority of Spaniards locating themselves on the centre of the political spectrum.

Therefore, it becomes in the interest of the PP to converge towards the centre in order to capture more votes, but also regain those lost to Ciudadanos. The emergence of Ciudadanos can be explained on a similar one dimensional left-right scale: the PP is too far to the right, the PSOE loses votes to Podemos, which it attempts to regain (perhaps foolishly according to the CIS data and the Downsian model), creating a ‘gap’ for the emergence of a new centrist party.

But, as political parties, especially in a bipartisan system, re-locate themselves to capture the ‘median voter’ and win the election, the moving of the parties has a number of consequences:

- This may decrease credibility of the party’s ‘signals’, as party position are sticky.

- There may be threats of competition from other parties. If a party moves to the centre, it might be ‘outflanked’ by other parties entering and competing for voters.

- If there are multiple dimensions for political competition, then converging on the median is not a stable equilibrium.

The effect of the PP attempting to regain the centrist vote back from Ciudadanos functions precisely in these two ways. The credibility of the party has decreased with the blurring of the lines of its ultraconservative stance. That said, beyond their shift in position, credibility has also decreased due to the corruption scandals that lead to the no confidence vote in the summer of 2018, which instigated Pedro Sanchez as the new Prime Minister. Then — and this is the hypotheses posited in this article — as the PP converges towards the ‘median voter’, in an attempt to regain votes and seats from Ciudadanos (somewhat successfully in 2016), a ‘space’ emerges, on the right of the PP, and the PP is ‘outflanked’ because Vox competes for voters. Therefore, the catalyst of Vox’s rise has been the shifts of parties on the political spectrum.

But, how can the movement of the PP be measured? Political scientists try to establish where parties are located on a Left-Right dimension by coding manifestos on individual policy dimensions, through expert surveys or the analysis of parliamentary votes. This, however, would be a far more ambitious project than the one presented in this article.

The Two-Dimensional Position of Spanish Political Parties

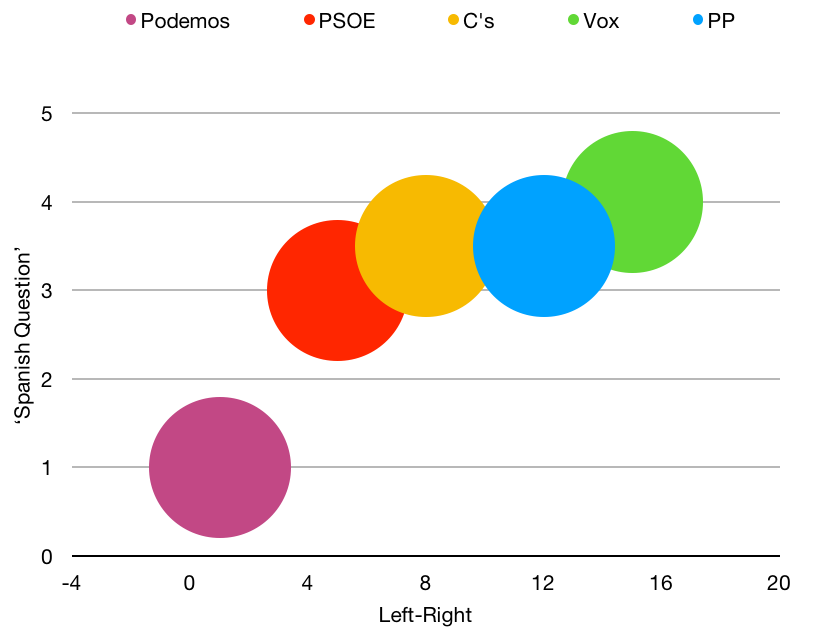

Nonetheless, despite the traditional far-right views permeating in Vox, Spanish political dynamics rise above the traditional left-right cleavage model. Vox and other parties have a multidimensional nature. The far-right party gained impetus from the Catalan illegal referendum in 2017 and the Spanish constitutional crisis. The ‘Spanish dimension’ therefore acted as a catalyst precipitating the achievements of Vox in Andalusia in 2018.

This multidimensional nature of Spanish politics incorporates elements of Lipset & Rokkan’s traditional cleavage model: owner/worker, church/state, urban/rural, centre/periphery. The centre versus periphery cleavage holds some validity, in the sense of regional nationalism exemplifying a ‘revolt of the peripheries’. But, the cleavage explanation is better in separating voters into advocates and adversaries on a certain issue, or voting for a certain party; ‘the issue of Spanish unity’. The second dimension can thus be framed as ‘the Spanish unity question’.

As aforementioned, Vox’s flagship policy is defending Spanish unity, illustrated in the party’s slogan ‘Andalusia for Spain’, which propelled them into these 12 seats. A similar stance is held by the PP, and Ciudadanos, despite not resembling Vox’s ‘Spain First’ branding, and the language by these respective parties differing strongly. Vox repeatedly characterises secessionists as ‘enemies of Spain’, dangerously echoing the Nazi tabloid Der Strümer’s depiction of Jews, or Robespierre’s ‘ennemi du peuple’ during the French Revolution, which could be punished by death.

Nonetheless, the PP’s stance will doubtlessly toughen under Pablo Casado, the newly elected leader of the PP, which announced a shift further to the right: reformation of electoral laws to ‘stop depending on nationalists and minority parties’ (outlaw independence parties), criminal response to secessionism, more restrictive abortion legislation. The first two, in particular, illustrate an attempt to retrieve votes from Vox on the ‘Spanish unity’ dimension.

Podemos, the far-left party, supports Catalan independence, and the PSOE is in between these two major blocks, offering dialogue with Catalonia in an attempt to exit the political crisis. In addition, in 2018, the PSOE allied itself to Basque and Catalan independentists in order to govern, which sparked outrage, and encouraged the unity of the three right-wing parties on the question of Spain, leading to the formation of a coalition in Andalusia, despite diverging on the left-right spectrum. In the graph below, I attempt a two-dimensional spatial model of Spanish political parties:

The ‘Spanish Question’ on the y-axis is difficult to qualify and this graph is only a rough representation of the position of political parties in Spain. The PSOE does not support secessionism, but its approach differs from that of other parties by calling for dialogue and also by relying on the support of independentist parties for governance in 2018.

Final points

Beyond the simplistic explanation that left-wing parties are responsible for the rise of far-right parties, and in this case the PSOE is responsible for Vox, the Downsian model suggests various degrees of responsibility lying within the entirety of the political spectrum. The difficulty of analysing the phenomenon is also a result of the multiple dimensions of political competition.

Since the 1982 regional autonomy arrangement, Andalusia had enjoyed PSOE governance. That said, in 2018, the historical win of Vox’s 12 seats was not only a result of the PSOE’s decline. The PSOE lost 7.4 percentage points or 400,000 votes from the previous election, but the PP also suffered a 6 percentage point loss, amounting to 300,000 votes, resulting in the fragmentation of right-wing support. The dwindling result nonetheless displayed a continuation of the PSOE as the single-largest party in the region with nearly 28% of votes, followed by over 20% for the PP. The fact that the two traditional and established political parties suffered such losses might also be explained by the general ‘democratic fatigue’ and ras-le-bol facing political systems across the globe. But, the questions of Spanish unity, and the battle for the position of ‘biggest supporter of Spanish Unity’ between the three right-wing parties will surely determine results in the general election in 2019.