The WTO’s Fall from Grace: Wavering Leadership

The WTO's outgoing Director General, Roberto Azevêdo, speaking at the 2015 Nairobi conference.

The WTO's outgoing Director General, Roberto Azevêdo, speaking at the 2015 Nairobi conference.

On May 14, 2020, the Director General of the World Trade Organization (WTO), Roberto Azevêdo, announced plans to depart from the role on August 31, 2020 – one year before the official end of his term. Citing a combination of personal and logistical reasons, the unexpected news will give the international community a chance to squabble over the selection of his next successor. Upon his reappointment in 2017, Azevêdo noted the successful negotiations that occurred during his first term with Bali (2013) and Nairobi (2015). However, trade relations between the United States and the rest of the world have since nosedived, leaving the WTO more fractured than ever.

The urgency of resolving fractures in global trade has only grown due to COVID-19. In the midst of pandemic, the WTO is currently predicting that trade will fall 13-32 per cent in 2020. While the WTO is maintaining a list of trade barriers related to COVID-19, it has not been a leader in initiating discussions to improve trade. In April, after announcing the French and German EU COVID-19 funding proposal, German Chancellor Angela Merkel reminded the world that despite the faltering of multilateralism — even before COVID-19 — a move towards nationalizing supply chains during the pandemic would hurt more than cooperation.

Pleased to join a discussion hosted by Chancellor Merkel w/ other international organization heads on the economic & social challenges posed by the #covid19 pandemic & how international cooperation – also on trade – can help countries recover more quickly https://t.co/Pn7xSKF9EO

— Roberto Azevêdo (@WTODGAZEVEDO) May 20, 2020

Troubled trade negotiations: from Geneva to Uruguay

The WTO emerged from the General Agreement on Trade and Tariffs (GATT) in January 1995, representing the international community’s next step in deepening its commitment to a rules-based trade order. Negotiated during the Uruguay Round and signed in 1994 in Marrakesh, the WTO’s founding legal texts added rules related to technical and other non-tariff barriers to trade, rules governing the trade in services, and intellectual property rights. Seven trade negotiation rounds occurred before Uruguay, each moving state parties into deeper and more beneficial trade agreements.

At the same time, an increasing number of states joined the GATT to reap the benefits of freer trade — between 1947 and 1994, one hundred new countries joined the original 23. As such, it should not come as a surprise that the Doha Round of negotiations that began in 2001 has yet to be concluded. Particularly, the trade interests of developing countries like Brazil, China, and India are at odds with the interests of developed countries like the United States and the states of the European Union. Like any international organization, the WTO is essentially a group project that cannot move forward unless all members agree, and as group membership grows, so does the number of diverging interests, thus making it more difficult to increase the depth of cooperation.

Career milestones: Azevêdo’s claim to fame

Roberto Azevêdo began his career in the Brazilian foreign service in 1984, rising to become one of the country’s top WTO litigators by the early 2000s. He was the second DG to come from a developing country, the first being Supachai Panitchpakdi from Thailand. He now joins the ranks of eight other former DGs of the GATT-WTO. The rules for selecting leaders of international organizations are often simple on paper, however, horse trading and unspoken agreements exist behind the scenes. In particular, the rise in membership at the WTO and the appointment of DGs from developing countries likely indicate that the selection system will need to move towards a regional rotation similar to that of the United Nations. This logic explains why African WTO members will likely push for Kenya’s former trade minister as Azevêdo’s successor.

Azevêdo’s career was built on advocating for developing countries. The Bali Package was the first trade negotiation after Uruguay to yield results: ministers made incremental steps to set up digital and agricultural agreements that help poor countries. Just two years later, the Nairobi Package made further strides for low-income countries, and while smaller in scale than Bali, it added evidence that Azevêdo would be the man to help repair the fractured organization. Notably, the agreement saw the definition of export subsidies expanded in order to reduce the amount that developed countries — especially the European Union —subsidize local agriculture at the expense of developing nations. This focus on developing country issues demonstrates why the European Union may be looking for one of their nationals to head the WTO.

In 2017, at the beginning of Azevêdo’s second term, the Buenos Aires ministerial conference did not reach the same success: the WTO’s 164 members found themselves in a deadlock, with a widening rift between the United States and China. The European Union’s Trade Commissioner was particularly bleak in stating that, “All WTO Members have to face a simple fact: we failed to achieve all our objectives”. Unfortunately, the 2020 ministerial conference to be hosted by Kazakhstan was cancelled due to COVID-19.

Trade, COVID-19, and the WTO

At first glance, it may seem that the current trade conflicts are nothing new: the WTO is based on the idea that states will have trade conflicts and that the organization can supply rules to help resolve them. Yet, the rules of the WTO itself are currently being challenged, different trade blocs have opposite agendas, and it is hardly imaginable that any candidate could satisfy them all. It is certain, however, that the next DG candidate will need to come from a less prominent, non-aligned country to gain support from all camps. The candidate will likely have a history as a career official or diplomat like Azevêdo, rather than a political career, which would be more polarizing.

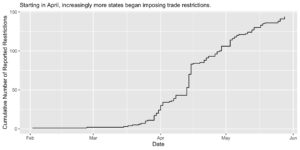

The new DG will be tasked with putting the WTO on a track towards renewal while the world recovers from COVID-19 — an evidently daunting task. The OECD is currently predicting that global GDP growth will drop 2.4 per cent this year, and combined with increased trade barriers, particularly in contentious issue areas like agriculture and food, it is unclear how the WTO can make a comeback. In the one area where trade talks seemed to be improving this year — fisheries subsidies — COVID-19 has halted the working group’s progress. While WTO officials urged the globe to engage multilaterally and to avoid trade barriers, the reaction has not been in kind, as seen with the creation of over one hundred new barriers. Will the WTO’s famed dispute settlement body bring bite to the organization’s bark, or are these the last words of a once great institution?

This is the first instalment of a two-part series on the WTO by this author.

The featured image, “Accession of Liberia 16 December 2015 – 23723699921” by World Trade Organization ,is licensed under CC SA 2.0.

Edited by Clariza-Isabel Castro