Protecting Pancasila: Indonesia’s Fight Against Religious Extremism

In early October, French President Emmanuel Macron gave a divisive speech outlining a strategy to tackle the threat that “Islamist Separatism” poses to French secularism. Macron’s proposal includes plans for government agencies to monitor foreign funding coming into mosques and Muslim schools run by supposed “religious extremists.” Macron’s speech has incited protests and boycotts across Muslim nations, including Indonesia, the world’s most populous Muslim country.

On November 2nd, over 2,000 protestors marched to the French embassy in the Indonesian capital of Jakarta to protest Macron’s allegedly islamophobic remarks. While Indonesian President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo condemned recent terrorist attacks in France, he warned that Macron’s rhetoric had insulted Islam by linking the religion to terrorism.

However, Jokowi’s words seem hypocritical given his previous “counter-Islamization” policies against the threat of religious extremism in Indonesia. Jokowi’s regulations on religious organizations mirror Macron’s proposal in several ways: the government now has stricter oversight of Islamic schools, and top government officials must undergo a vetting process in order to weed out hardline Islamists.

Jokowi has justified this legislation with the need to defend Pancasila, Indonesia’s founding ideology, which advocates for religious pluralism. To a degree, Indonesia’s fight to uphold Pancasila parallels Macron’s quest to defend the secular values so dear to the French republic. However, Indonesia’s push to neutralize the threat of radical Islam predates post-9/11 anxieties about religious extremism, rooted in enduring debates about the role of Islam in Indonesia.

Indonesia has not been immune to the rising tide of religiously-motivated violence worldwide. In 2002, over 200 people were killed during a bomb attack planned by al-Qaeda affiliates in Bali, waking up Indonesia to the danger of domestic terrorism. Indonesia has also seen increasing attacks on religious minorities, threatening the country’s history as a tolerant nation. For example, in August 2013, a group of hardline Islamist militants orchestrated a bomb attack on a Buddhist temple in Jakarta.

Religious tensions have also permeated Indonesia’s political arena. The 2019 presidential elections pitted incumbent president Jokowi against former Suharto-era General Prabowo Subianto. The role of Islam polarized the campaign, with Jokowi mobilizing a large coalition of moderate Muslims and religious minorities. Meanwhile, Prabowo drew on support from hardline Islamist groups, such as the Islamic Defenders Front. However, after Jokowi won the election with over 55 per cent of the vote, he appointed Prabowo as his defence minister — effectively ending Prabowo’s short-lived alliance with hardline Islamists.

The increasingly divided debate over the role of Islam has motivated Jokowi’s push for legislation to fight against the “threat of Islamization” in Indonesia. In his 2019 Independence Day address, Jokowi warned of social media’s impact in contributing to a rise of intolerance and terrorism in Indonesia. He also issued a warning to civil servants that he would not tolerate hardline Islamists betraying the principles of Pancasila, grounded in religious pluralism and democracy.

Jokowi first introduced stricter government regulations on mass organizations back in 2017, giving government agencies greater oversight to ban organizations deemed “too extremist.” In 2019, the Jokowi government introduced a vetting plan for top government agencies and state-owned companies, in order to screen civil servants for Islamist views. These pieces of legislation have been instrumental in banning a prominent Islamist organization, Hizbut Tahrir Indonesia (HTI). Although HTI is a nonviolent organization, the group’s goal of creating a caliphate was deemed to be in contradiction with the Indonesian Constitution and Pancasila.

Although Jokowi’s fight against radical Islam could be perceived by Indonesian Muslims as an affront against Islam as a whole, two of Indonesia’s largest Islamic organizations — Nahdlatul Ulama and Muhammadiyah — have supported these policies in the hopes of discrediting religious extremism. Other Islamic groups have backed the government’s decision to ban Islamist groups, with the leader of the Islamic Organization Friendship Body stating they “even encouraged the government [to ban HTI] sooner than later.”

These counter-Islamization policies, however, have been criticized based on human rights concerns. Watchdog groups have warned that these laws give Jokowi’s government excessive discretion to ban organizations, threatening the freedom of civil society. Others have criticized Jokowi by alleging that in a similar manner to politicians in Western societies, he is engaged in “fear-mongering” against an outsized Islamist threat. For example, despite the religious tensions underpinning Indonesia’s 2019 elections, conservative Islamist parties continue to do quite poorly compared to Indonesia’s secular parties. A fragmented bloc of Islamist parties only garnered 20 per cent of the vote in Indonesia’s legislative bodies, which is consistent with previous elections.

The absence of a united and successful Islamist party in Indonesia begs the question — why have Indonesia’s top politicians regarded radical Islam as an existential threat to the nation? The answer lies in the country’s historical divide between “Conservative” and “Moderate” Islam, dating back to independence from the Dutch in 1945.

When General Sukarno declared Indonesia’s independence on August 17, 1945, he put forth a vision of Pancasila. Sukarno, as the first president of a nation encompassing over 300 ethnic groups, pushed for Pancasila in order to prevent division based on religion, ethnicity, and ideology. Notably, although Islam is recognized as a religion in Indonesia under Pancasila’s first principle — “belief in One True God” — Islam was not established as Indonesia’s state religion. The absence of Islamic law in Indonesia’s constitution and political institutions has been a longstanding grievance of conservative Muslims in Indonesia.

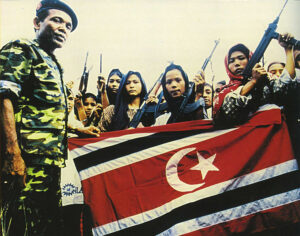

Despite Indonesia undergoing numerous regime changes, Pancasila has remained synonymous with Indonesian nation-building throughout its history. During the New Order dictatorship (1966–1998), General Suharto invoked Pancasila to repress civil society groups, particularly Islamist organizations, that spoke out against the regime. Despite Pancasila’s association with authoritarian regimes, democratically-elected politicians, including Jokowi, have defended Pancasila as the nation’s founding ideology. The nation’s enduring issues with separatist movements — such as the Free Aceh Movement and Free Papua Movement — have motivated Indonesian leaders to promote Pancasila as a sign of the nation’s commitment to pluralism.

Despite the potentially nefarious intentions behind politicians’ commitment to Pancasila, the ideology receives genuine support from the majority of Indonesians. According to an August 2019 poll, 70 per cent of Indonesians accept Pancasila as the state ideology, while only 5 per cent and 13 per cent of Indonesian support a caliphate and the adoption of Islamic law, respectively. The fact that “conservative” Islam has remained a minority in Indonesia’s political system and population as a whole can explain why Islam is claimed to be under attack by conservative leaders, despite the country being predominantly Muslim.

Indonesia’s desire to commit to Pancasila in the fight against radical Islam parallels the current debates in Western countries about the limits of religious pluralism. However, Indonesia’s counter-Islamization policies are also rooted in a longstanding desire to unite the ethnically diverse country under the Pancasila ideology. In this way, Pancasila may share similarities with the importance that secularism holds in Western societies. While Pancasila and secularism are ideologies that in theory allow for religious pluralism, state commitment to these ideologies has marginalized the “minority” of Muslims both in Indonesia and the Western world. As Indonesia tackles the growing threat of religious extremism within its borders, it remains unclear if the nation can continue to adhere to the “tolerant” and moderate Islam espoused by its political leaders.

Featured image: “Meet & Greet | Jokowi + INTI” by hendrikMINTARNO is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Edited by Devanshi Bhangle