Hostage Diplomacy: The Canada-China Prisoner’s Dilemma

On December 1, 2018, Meng Wanzhou — Chief Financial Officer of Chinese telecom firm Huawei and daughter of its founder — was arrested at Vancouver International Airport by the RCMP on a US extradition request. Soon after the news became public, Beijing officials requested that Canada “immediately correct the mistake” and release her. But as Meng made her first appearance in a BC court for the extradition hearing, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau held that it was an independent legal proceeding; intervention would violate Canada’s rule of law. Then, on December 10, 2018, Canadians Michael Kovrig and Michael Spavor, now famously known as the “two Michaels,” were detained in China on espionage charges in what has been widely interpreted as retaliation to Meng’s arrest.

Over two years later, the Huawei executive and the two Michaels remain stranded in ongoing legal proceedings in one another’s home countries, a situation dubbed “hostage diplomacy” by Canada’s Defence Minister Harjit Sajjan. This prisoner’s dilemma between Ottawa and Beijing, in the most literal sense, has prompted the deterioration of Canada-China relations in recent years.

A tale of two trials

Following her arrest in Vancouver, the US Department of Justice formally laid out charges of fraud against Meng Wanzhou in 2019. She faces allegations of deceiving American banks about Huawei’s ownership of Iranian tech company Skycom, which has since been dissolved. Huawei maintains that Skycom was merely a business partner, but investigative journalists at Reuters claim that leaked documents reveal Huawei “effectively controlled Skycom.” If so, Huawei violated US sanctions against Iran by using a New York branch of HSBC to process transactions involving Skycom. Hence, as Huawei’s CFO, Meng will be criminally prosecuted for bank fraud if she is extradited to the US.

In the meantime however, Meng is on trial in the British Columbia Supreme Court to determine whether she will be extradited to America in the first place. She has been living in a Vancouver mansion since her release in late 2018 on a $10 million bail. The final round of her hearings began in March 2021 and will conclude in May. Meng’s defence has questioned the constitutionality of her detainment, contending that Canadian border officials’ searching of her electronic devices prior to the RCMP’s arrest violated legal rights. China’s embassy in Ottawa has called the US fraud charges against Meng politically motivated — part of an “agenda to suppress Chinese high-tech enterprises.”

Across the Pacific, the espionage trials of the two Michaels imprisoned in China began in March 2021. Michael Kovrig was a diplomat on unpaid leave from Global Affairs Canada when he was arrested in 2018, thus not qualifying for diplomatic immunity. He is currently being held in a Beijing prison. Michael Spavor was a businessman based along the China-North Korea border, one of few westerners to have personal relations with Kim Jong-Un. He is imprisoned in Dandong, near the North Korean border.

When Kovrig made his first court appearance in Beijing on March 22, diplomats from a multitude of countries arrived to express solidarity but were denied access to the courtroom. The Canadian embassy stated that it was “very troubled by the lack of access and lack of transparency.” Spavor’s first hearing occurred on March 19 in Dandong. Periodically, the two Michaels have been permitted contact with Canadian consular services and their families.

Trudeau says it is “obvious” that the espionage charges against the two Michaels were fabricated. Though trials usually take two to six months to conclude, former Canadian ambassador to China Guy Saint-Jacques already expects “a very severe sentence.” Last year, 99.97 per cent of all charges resulted in a conviction in China. Espionage is punishable by life, with a minimum sentence of 10 years.

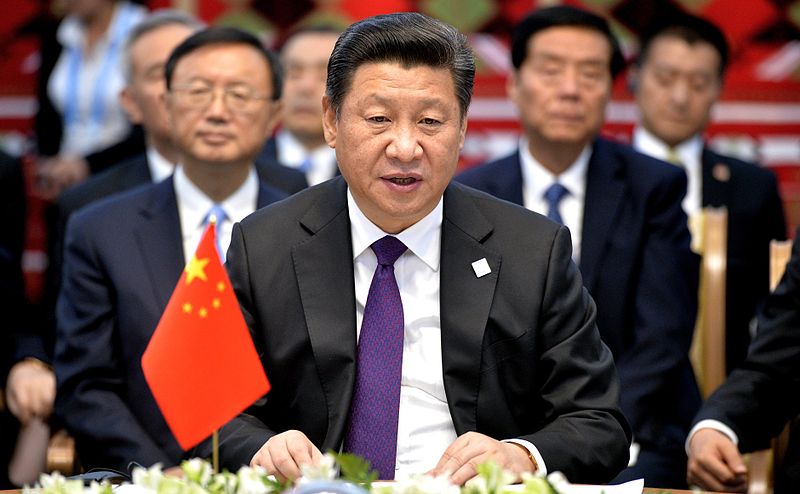

The detainment of the two Michaels is contained in China’s shift towards a more assertive foreign policy — one of the pillars of Xi Jinping’s presidency.

Avenues to freedom

US President Joe Biden has affirmed his willingness to work with Canada to secure the return of the two Michaels — “human beings are not bargaining chips,” said the President. But what avenues do the two Michaels — and Meng — actually have to freedom?

In Canada, the 1999 Extradition Act permits the Attorney General to call off extraditions. Thus, one option for Trudeau is to ask Justice Minister David Lametti to cancel Meng’s trial and presumably have her returned to China in a sort of prisoner swap for the Canadians. Former Prime Minister Jean Chrétien recommended this course of action in 2019, but Trudeau’s second-in-command, Chrystia Freeland, asserted that Canada must honour the rule of law by avoiding political interference in its legal proceedings. Furthermore, caving in to “hostage diplomacy” would set a dangerous precedent whereby foreign (or domestic) actors view the detainment of Canadian citizens as a means of getting concessions from Ottawa. It should not go without mentioning that in 2019 Trudeau faced massive backlash for pressuring his then-Attorney General, Jody Wilson-Raybould, to interfere in the SNC-Lavalin fraud case. The scars of that scandal have most certainly made this Prime Minister particularly resistant to the idea of pressuring another Attorney General towards legal interference.

The Trudeau government could also attempt a prisoner swap by renouncing the Canada-US extradition treaty, nullifying Meng’s extradition trial in BC. Yet, this option would still set a dangerous precedent about the effectiveness of hostage diplomacy. Furthermore, such a move would undoubtedly put a strain on Canada’s relationship with America without necessarily improving relations with China, ultimately leaving Ottawa more isolated than it already is.

With interference in Meng’s trial seemingly off the table, the Canadian government has sought to harness international opinion as a weapon of pressure on Beijing. In 2020, Canadian ambassador to the UN, Bob Rae, accused the Chinese government in front of the General Assembly of “bullying” and arbitrary detainment with “terrible” living conditions. Additionally, Foreign Affairs Minister Marc Garneau is campaigning to get countries to sign the Declaration Against Arbitrary Detention in State-to-State Relations — an international declaration for which 57 nations have expressed support thus far. Human Rights Watch says that while the imprisonment of the two Michaels “epitomizes this despicable practice,” supporters of the Declaration should not turn a blind eye to politically motivated detentions in Guantanamo, Saudi Arabia, and Israel, among others.

Given the limited influence Canada holds on the world stage, Guy Saint-Jacques believes the middle power is “in the hands of the Americans” when it comes to negotiating the release of the two Michaels.

Days after Meng’s arrest in 2018, President Trump, when asked if he would consider pressuring the Justice Department to scrap her charges, stated: “If I think it’s good for what will be certainly the largest trade deal ever made — which is a very important thing — what’s good for national security — I would certainly intervene if I thought it was necessary.”

Trump’s remarks were met with backlash for their seeming disregard for judicial independence. It should also be noted that, in those words, the President implied a willingness to use Meng’s detainment as leverage in trade negotiations — the very crime that the West has condemned China for. Within weeks, the Trump administration reversed course, stating that interference in Meng’s case was off the table. President Biden continues to hold this line.

In March 2021, members of the Biden administration engaged in high-level discussion with CCP officials in Alaska. But despite Biden’s promise of his commitment to the two Michaels, the Canada-China prisoner’s dilemma did not come up in the talks between Chinese and American diplomats. Instead, the meeting deteriorated into angry exchanges on human rights abuses of Uighur Muslims in Xinjiang and African-Americans in interactions with police, signalling growing US-China tensions.

In late 2020, investigative journalists discovered that the US Justice Department was negotiating with Meng’s legal team on a possible plea agreement, likely involving substantial fines but allowing her to return home to Shenzhen without serving a sentence in the US. Supposing that these negotiations have continued, they are probably the only remaining avenue for Meng, and especially the two Michaels, to avoid long-term imprisonment. Still, Canadian Senator Yuen Pau Woo fears that a settlement between the US Justice Department and Meng’s camp would not necessarily guarantee freedom for the two Michaels. If the Canadian government were to continue its non-involvement approach to Meng’s legal affairs, a settlement on her fraud charges could be “misinterpreted on the Chinese side as a problem that was resolved purely by D.C. and Beijing.” It is therefore vital that “Canada’s fingerprints be all over” any legal settlement between Meng and the Justice Department, if the two Michaels are to be free at last.

Featured Image: “China International Media Tour, January 2014” by Ontario Canada, licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0.

Edited by Jessica Maloney