Globalization’s Achilles Heels: the Precarious Links of Global Commerce and What it Means for Canada

For six days in March 2021, global commerce ground to a halt as tugboats and dredgers tried to free the 400 metre-long Ever Given container ship blocking the Suez Canal. The navigational hiccup resulted in a logistical and financial nightmare for the international shipping industry: nearly $9 billion in goods were held up each passing day, cargo ship rental prices spiked, and supply chains already reeling from the COVID-19 pandemic were stretched even further. The blockage exposed the precariousness of globalization, and in particular its reliance on a few critical junctions throughout the world that are of tremendous strategic significance. As the world becomes even more interconnected, and as melting sea ice sadly opens more and more of the Arctic to shipping, global demand for alternative shipping routes will only grow stronger. The Ever Given fiasco gives pause to examine where the linkages of the future lie, such as Canada’s Northwest Passage, and examine the merits of this link’s development for global commerce.

The man-made Panama and Suez Canals are of tremendous importance to our interconnected world, handling approximately 17 per cent of global trade combined. Natural geography also has produced concentrations of high-volume shipping, such as Southeast Asia’s Strait of Malacca and the Strait of Hormuz in the Persian Gulf. Many of these “choke points,” which international commerce relies on, are vulnerable to a range of risks. Egypt’s political instability following the Arab Spring raised anxieties that the Suez link would be targeted by opposing factions. In 2019, the Strait of Hormuz, which handles 20 per cent of the world’s oil supply, was the site of escalating tensions between Iran and Western powers, with oil tankers being seized by the Iranian Revolutionary Guard. The Strait of Malacca is prone to poor visibility, piracy, and collisions resulting from its narrow width and high traffic.

It is not surprising that powerful states have tried to protect their interests in light of their dependence on these unreliable passageways. Egypt’s nationalization of the Suez Canal in 1956 was perceived to be so disruptive to Western interests that the UK, France, and Israel invaded – only to be rebuffed by the international community. Canada’s Lester B. Pearson famously championed the first UN Peacekeeping operation in response to the Suez Crisis, a feat that marked a golden age for Canadian foreign policy. The United States also engaged in the geopolitics of shipping when Theodore Roosevelt supported Panamanian rebels to secede from Colombia in exchange for the right to build the Panama Canal. From 1904 to 1977, the US held a colonial-like claim on the territory immediately adjacent to the waterway to ensure its protection from hostile forces. Though Jimmy Carter gave up that mandate as a gesture of goodwill towards Latin America, the US would return over a decade later, with George Bush Sr. invading Panama in 1989 to topple President Noriega, who had since fallen out of America’s good graces.

As China develops trade links around the world, it, too, has made efforts to diversify its trade links. Nearly 80 per cent of China’s oil imports pass through the narrow Strait of Malacca, and rising tensions with neighbouring India add further insecurity to the links between the Chinese mainland and the Middle East and Africa. One key part of China’s “Belt and Road Initiative,” a grand strategy to reroute trade towards China, is the “Maritime Silk Road,” which involves a string of ports and naval bases across the Indian Ocean. Projects such as the Chinese-built Gwadar Port in Pakistan, linked to China through the “Pakistan-China Economic Corridor,” intend to provide crucial alternatives to the politically fraught conventional shipping route.

The COVID-19 pandemic notwithstanding, the forces of competition and globalization are set to put even more pressure on the jugulars of international commerce. As attention is turned to constructing more physical links to rival existing canals and railways, such as a Chinese-funded “dry canal” through Colombia, so too will the world shift its gaze to the navigable waters in Canada’s north. Melting sea ice caused by global warming has made southerly routes viable for summer passage; in fact, 160 ships made a trans-Arctic voyage in 2019, representing a 44 per cent increase over the past five years. Nevertheless, there remains considerable skepticism about whether the Northwest Passage would be suitable for larger vessels on longer intercontinental journeys. Search and rescue is challenging, given the remoteness of the landscape, and the unpredictability of ice floes makes it a perilous route even amidst warming climates. Furthermore, it is the deeper northern routes that would be most appropriate to handle large ships, but those will remain frozen over for the time being. The southern route has several choke points, and is at some straits only 10 metres deep, compared to the Suez’s 24 metre depth.

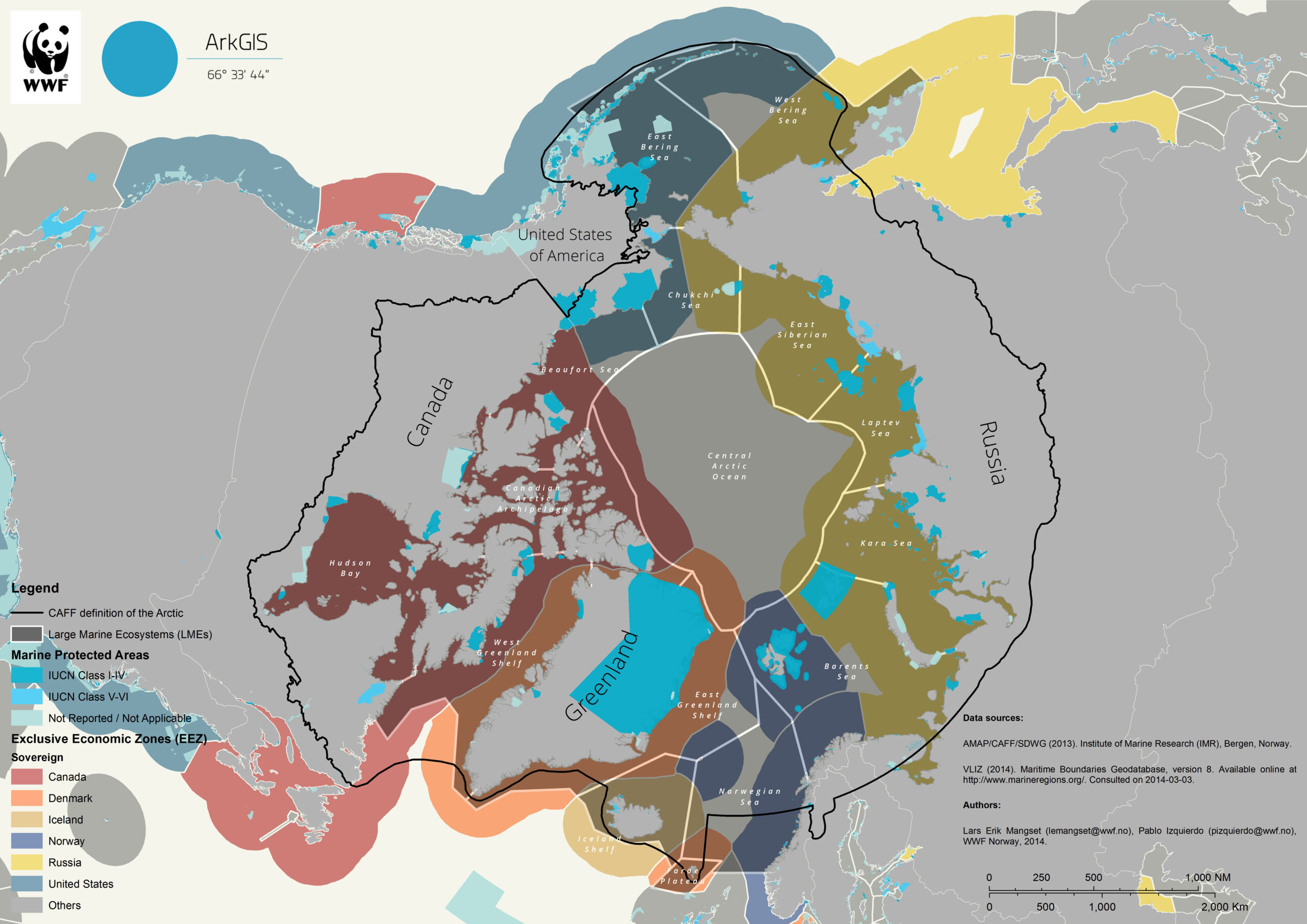

The international law governing the Northwest Passage is controversial. The US sees the strait as international waters, which means Canada cannot exclude vessels on innocent passage. The US cites international precedent for this interpretation, which states that an international strait is a geographic situation that “connects two parts of the high seas and is used for international navigation.” Canada, meanwhile, asserts that the Northwest Passage is internal waters and not subject to the freedom of transit passage under international law. Furthermore, Article 234 of the 1982 UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (LOSC) allows coastal states to regulate traffic through ice-covered areas within their exclusive economic zone (EEZ) for environmental protection. Indeed, even with unanimous agreement on Canadian sovereignty over the passageway, environmental concerns may warrant exclusion of large ships that disrupt Arctic ecosystems. Nevertheless, the US affirms that any exclusion of vessels under Article 234 would constitute a violation of freedom of the high seas.

In opposing Canadian sovereignty over the Northwest Passage, the US is making a short-sighted error. While it is of considerable benefit for commerce and American warships to have a viable, quicker alternative to the Panama Canal, there are also considerable risks to treating it as an international strait. Without Canadian jurisdiction, there would be no legal authority to block the shipment of arms, drugs, or other nefarious cargo bound for recalcitrant regimes. Instead, as international attention turns to the warming Arctic waters, the US would better serve its own strategic interest by allowing a dependable ally to regulate the vessels traversing their internal waters.

The blockage of the Suez Canal demonstrated to the world the risks of relying on a handful of arteries for the circulation of the global economy. Warming waters and increasing interconnectedness across the world means that the demand for Arctic passage as an alternative to precarious straits and canals will only grow stronger. Canada and the US should be proactive in promoting Canadian sovereignty over its internal waters in order to have authority over what could very well be another crucial link in the web of international commerce in the decades to come.

Feature Image: “Panama Canal – Cargo Ships 2” by thinkpanama is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0

Edited by Max Clark