Costa Rica’s Caribbean Coast: Marcus Garvey’s Legacy as a Tool of Resistance

The fight against cultural erasure in the Afro-Costa Rican community

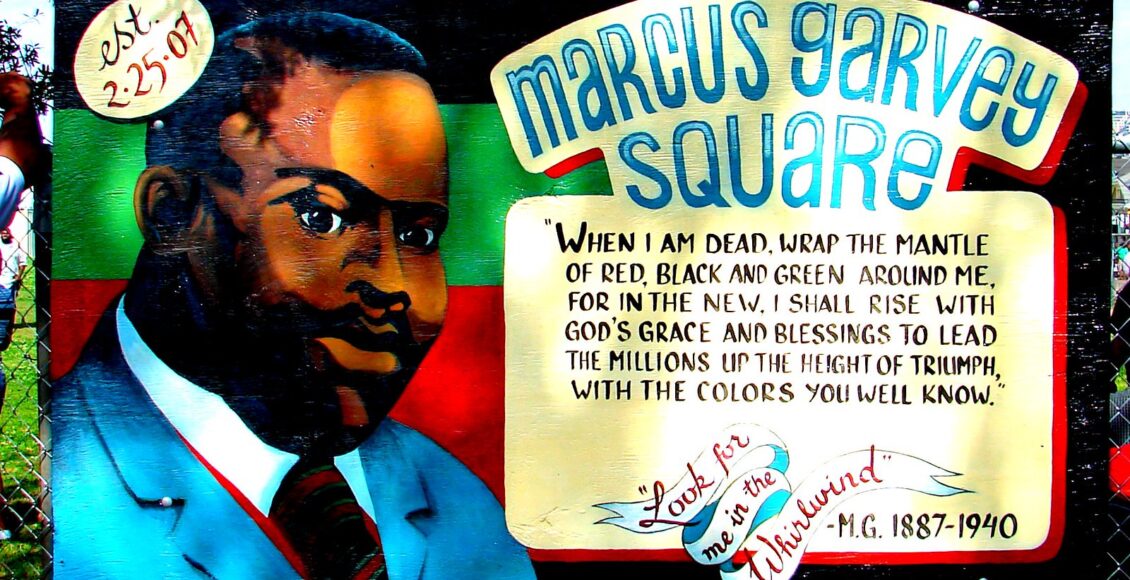

Marcus Garvey was a crucial and controversial Jamaican pan-Africanist activist. As an immigrant and the first black nationalist in the United States, he founded the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA), an organization dedicated to the advancement of Afro-descendants. He is also known for advocating Afro-descendants’ return to the African continent through the Black Star Line shipping corporation. Born in Jamaica in 1887, Garvey relocated to Costa Rica in 1910. Like many West Indians at the time, he relocated to Puerto Limón, finding employment through the United Fruit Company (UFC), the predecessor to the present-day Chiquita Brands International. The UFC was an American enterprise exporting bananas from Central America to the US. Due to linguistic ties between Americans and British-colonized West Indians, Jamaicans and Barbadians comprised the primary labour force on the banana plantations. Marcus Garvey worked as a time-keeper at a UFC plantation, where he witnessed the horrific conditions faced by farmers and harvesters. These injustices inspired him to found a local journal, the Nation, to shed light on these instances.

Working conditions on banana plantations were similarly poor across the banana republics and were a source of significant political unrest within Central America. The corporation was notorious for interfering in government processes in countries it operated in, often at a deadly cost. One instance was the Banana Massacre, which occurred near Santa Marta on Colombia’s Caribbean Coast. On December 5, 1928, Colombian armed forces murdered local UFC workers for protesting their labour conditions.

Garvey did his best to fight against the hegemony of the UFC, but he was not a popular figure initially in Limón. For the most part, his message resonated only with fellow West Indian immigrants who arrived in Costa Rica around the same time. In 1911, his newspaper was set ablaze, an incident for which he received little support. Due to his initial failures, he left Costa Rica and travelled across Panama, Colombia, and other Central American countries along the Caribbean coast. Throughout this journey, he noted Afro-descendants living through similar conditions at the hands of the fruit corporations. Garvey would coin these observances as a “universal degradation of the black race,” inspiring his vision for the UNIA. Following his tour of Central America and some time in England, Garvey returned to Kingston, Jamaica in 1914 and founded the UNIA’s first branch. Throughout the decade, about a thousand branches opened in the Americas and West Africa.

The Puerto Limón branch, founded in 1922, is the 300th. It describes itself as a “social, friendly, humanitarian, charitable, educational and expansive society” focused on protecting the rights of Afro-descendant people within the community. The UNIA branch also works on the preservation of Afro-Caribbean culture in Puerto Limón. Alongside hosting events year-round, the UNIA also connects with the community through its own radio show on a local station hosted by current UNIA president Winston Norman.

Since its establishment, other community organizations have come about that are dedicated to responding to the needs that the UNIA cannot address. These organizations are crucial, as the pandemic has made it even more difficult for Limón’s UNIA branch to stay proactive. One other organization in town is the Solo Nos Humanitarian Foundation, headed by Velvet Waite, a real estate agent and community leader in the town.

Her most recent endeavour involves putting together an English school for the youth in Limón to transmit culture and traditions. The project is in homage to her grandfather Doudley Waite, who founded one of his own during his time. Today, less of the younger generation speak Limonese Patois and English, instead favouring Spanish. Language is an important marker for elders of the community, and not knowing their own is seen as disengaging from the Afro identity. Another reason for the disconnect between youth and their traditions is rising urban migration.

The Limón province is situated in a rural region of Costa Rica, where advanced infrastructure is limited. From speaking with locals, there is a lack of educational opportunities in the Limón area. There are only two main postsecondary establishments: the Caribbean headquarters of the University of Costa Rica and the Colegio Universitario de Limón. Both offer only limited technical courses in culinary, marketing, customer service, and entrepreneurship. Anyone wishing to pursue a more sophisticated degree must either move to the capital of San Jose or pursue their studies abroad. Many youths have moved out of the province for educational purposes within the last decades, making it difficult to pass down culture and traditions.

This increasing trend of urban migration has unravelled concurrently with the violent gentrification of Puerto Viejo de Talamanca, locally known as Wolaba. According to locals I’ve spoken with, many ex-pats bought their land after a sudden disease rotted a large percentage of cacao plantations in the 1980s. In the years following, a prominent European ex-pat community has settled into the town. For example, Punta Mona, featured in Zac Efron’s Netflix travel series Back to Earth, is one notable foreign permaculture village. The episode received criticism for its lack of Indigenous representation — despite being located on their traditional land and benefitting from their resources. Unbeknownst to viewers, however, the episode is quite telling of how the town resembles most of the time. Foreigners have founded yoga retreats, community permaculture cohabitation spaces, and vegan restaurants, all within the backdrop of Afro-Caribbean and Indigenous Bribri land.

The Afro-Costa Rican community has recently struggled to reclaim Liberty Hall, a subsidiary chapter of the UNIA’s Limón branch blessed by Marcus Garvey himself. Located in the center of town, the hall was a space for the Afro-Costa Rican community to congregate — until associations such as Camará de Turismo took it over. The principal members of this group are foreigners and Hispanic Costa Ricans, with very few Afro-Costa Ricans participating. While tourists now view the building as La Casa de la Cultura, a space to purchase art pieces by local artisans, local Afro-Costa Ricans see Liberty Hall as a central part of their heritage. Reclaiming the space has been a slow and disappointing process, with only a few, such as Velvet Waite, left advocating for it.

“The mistake that the community made was to sit back and allow these things to happen because they didn’t want to disrupt the peace,” shares Velvet Waite. “They didn’t set the rules of engagement and are feeling the backlash of that now.”

The experiences of the Afro-Costa Rican community are tied to a grander narrative within Central America. As questions of identity and labels come out of the woodwork, Afro-descendant people in Central America are confronted with the issue of double consciousness: becoming hyper-aware of their perception from both white and Eurocentric Hispanic lenses. From Mexico to Costa Rica to Colombia, Afro-descendants native to the region face continuous erasure on local and global scales, rapidly contributing to the dissipation of their identity.

Communities along the Caribbean Coast continue to work on the self-preservation of their culture and traditions as foreigners increasingly establish themselves and their influence in the region. Thus, for the natives of Wolaba, Marcus Garvey’s legacy is a symbol of their resistance.

“Marcus Garvey’s legacy for me signifies that people of Afro-Descent should never depend on anyone other than themselves for success, for community, for structure, for growth, for authority, for power and for progress.” –Velvet Waite

Featured Image: “Marcus Garvey Square” by Mark Gstohl is licensed under CC BY 2.0

Edited by Grace Parish