A Canadian Take on the Democratic Primaries

It’s a cold Saturday evening in Manchester, New Hampshire, and thousands of people are flocking towards the warmth of the Southern New Hampshire University Arena. In just a couple of hours, all of the Democratic presidential candidates will arrive to pitch themselves one last time to voters before the state’s first-in-the-nation primary (with Iowa occurring a few days prior as the country’s first caucuses.) The cold does little to lessen the energy of some of the most passionate supporters. A Bernie Sanders marching band braves the freezing conditions, while volunteers from other campaigns make their presence felt by distributing flyers, hoping to win over some undecided voters.

On February 8, my friend and I travelled down to Manchester to get a taste of the American political machine. After my involvement in Canada’s 2019 federal elections, I thought that I understood the gist of electoral politics, but I couldn’t have been more wrong. Canadian and American democracies are fundamentally different, but these differences extend far beyond our respective structures of government and electoral processes. In the United States, politics reach down into the grassroots in such a way that it becomes an intrinsic part of someone’s identity. As I quickly learned, the American political system is a beast of its own when it comes to size, enthusiasm, and polarity.

In 2016, New Hampshire Democrats made up only 0.8% of all national voters in the Democratic Primary. Yet, every four years, New Hampshirites continue to be disproportionately favoured in the Democratic primaries due to the state’s early voting. People from across the country, and even the globe, leave their homes and jobs to campaign in New Hampshire with the hopes of giving their candidate a head start in the nomination process. Alyssa, an Australian that I spoke with in New Hampshire, was spending a couple of weeks with her friend knocking on doors for Bernie Sanders in the state’s smallest towns. Julie, a Buttigieg field organizer and supporter from Washington state, proudly donned a button reading “I travelled 2500 miles for Pete!” Drew, from Maine, had travelled all the way to Manchester just to see Elizabeth Warren in person. Not only had people travelled from far and wide, but many of them had been supporting their candidate for months if not years, with the general election still nine months away.

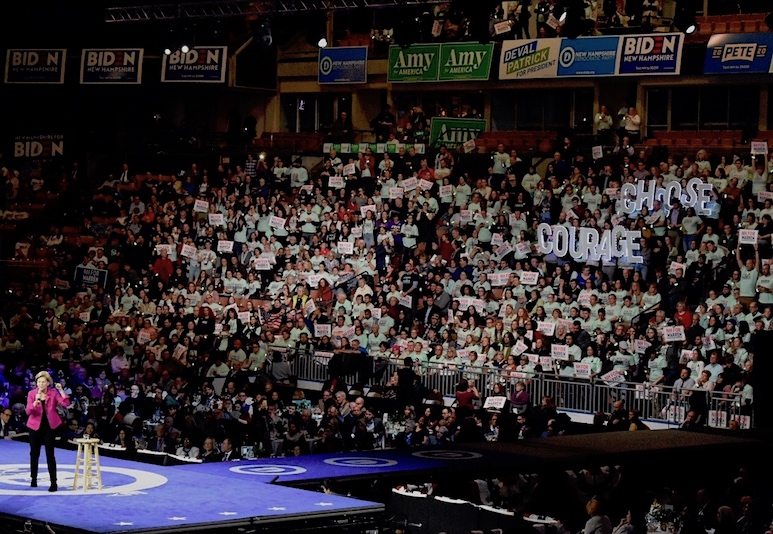

Even though the New Hampshire primary takes place five months before the Democratic National Convention, the New Hampshire Democratic Party nevertheless managed to sell out a 10,000 person stadium in Manchester for the occasion. In comparison, the Nova Scotia Conservative Party held an event on February 8th to showcase the 2020 Canadian Conservative leadership candidates in Halifax. Although the population of Halifax is four times larger than Manchester, New Hampshire, only 500 people attended the event. In Canada, citizens are required to be party members in order to vote in leadership elections, while in the U.S., many states, including New Hampshire, have open primaries that allow all citizens to participate regardless of party registration. As a result of these differing processes, relatively fewer Canadians are involved in Canadian leadership races. For instance, only 0.39% of Canadians (141,000) voted in the 2017 Conservative Party leadership election, while nearly 15% of all eligible Americans voted in the 2016 Democratic primary. While Canadian voters do turn out in large numbers and become politically involved in the weeks before a general election, the grandiosity of American elections has the unique ability to seize the attention of millions of people for years in advance and for years at a time.

Owing perhaps to this staunch candidate loyalty, American politics also generate incredible enthusiasm from individuals, particularly among young people. For the 2020 Democratic New Hampshire primaries, the stadium where the candidates spoke was divided into factions. A sea of Pete supporters wearing yellow “Pete for New Hampshire” t-shirts sat opposite from a mass of mint-green Warren shirts, who in turn engulfed a pitiful handful of Biden supporters. As the stadium began to fill up, enthusiastic college-aged volunteers led each support group in a series of chants and cheers for their respective candidates. Cries of “BOOT EDGE EDGE!” clashed with repetitive screams of “BERNIE! BERNIE!” Many presidential candidates rely heavily on the enthusiasm of young Americans to either make or break their campaign. In this New Hampshire primary, Bernie Sanders came out victorious, notably securing 47% of the vote among 18-29 year olds. Whereas Joe Biden only won 4% of the same age group and ended in 5th place.

While Canadians are also politically involved, it pales in comparison to the United States where people’s lives seem to revolve around politics and their favourite politicians. A 2019 study showed that many Canadians feel that their political leaders are not concerned about the average citizen. As a result, political apathy can develop among the general population. Even major Canadian political events fail to draw large crowds. On Canada’s election night in October, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau delivered his national victory speech to a sparsely filled room at the Montreal Convention Centre.

While scale and enthusiasm are some positive traits of American elections, American politics are also prone to deep-rooted polarisation. In New Hampshire, ahead of the Democratic primaries, Trump supporters walked down the street calling out, “We don’t need you Communists!”, while a Bernie Sanders marching band tried to drown out the noise. As we were crossing a busy intersection in downtown Manchester with a Pete Buttigieg supporter, a small group of people carrying Trump signs and wearing MAGA hats also started crossing the street. The Buttigieg supporter stopped abruptly in the middle of the intersection as cars began to drive past, turned to us and said “Sorry. I’m not with those people.” She then refused to walk within 15 feet of them.

The size and energy of American politics may be the source of such deep-seated polarisation. When someone’s identity is so powerfully intertwined with their political perspectives, tensions are prone to boil over and people begin to view each other as political opponents rather than fellow citizens. In Canada, on the other hand, a person’s political opinions do not appear to be as profoundly tied to their personal identity. Americans tend to vote repeatedly for the same party throughout their entire lives while just 28% of Canadians consider only one party when voting. Polarisation exists in Canadian politics, but it has come to define American politics. For better or for worse, this election has transformed into a years-long circus that grips the attention of millions of people. Where elections are meant to bring people together, this one seems to be pushing people further apart.

The featured image is “Choose Courage” by Adam Steiner

Edited by Rebecka Eriksdotter Pieder