A Credibility Problem

On September 23rd, US bombers and fighter jets flew close to North Korea’s Eastern coast. Dana White, a pentagon spokeswoman said the flyover sent a “clear message that the President has many military options to defeat any threat”. The show of force came after a week of intensifying rhetoric between the two countries which included Donald Trump threatening to “totally destroy” North Korea at the United Nations General Assembly. The exchange culminated with the North Korean regime affirming its right to shoot down US warplanes after it called Donald Trump’s recent statement a “declaration of war“.

Military threats between the two countries are nothing new. In 1994, North Korea shot down a US helicopter that was in North Korean airspace and, in 2010, the US and South Korea conducted military training exercises to “send a clear message to North Korea that its aggressive behavior must stop”. In 2013, American B-52 bombers flew over North Korea in a move similar to the events of September 23rd. The United States’ recent North Korean policy, while cruder, has mostly remained the same. Its consistent failures to deter North Korea lead us to question its inefficacy. Ultimately, the failure lies with the diminishing success of America’s deterrence policy.

Deterrence is “the threat of force in order to discourage an opponent from taking an unwelcome action”. Deterrence theory rose to prominence in the Cold War due to the invention of nuclear weapons. The newfound power of nuclear weapons was so great that any aggressive move could be met by apocalyptic military destruction. During the Cold War, while tensions were high between the US and the USSR, the mutual deterrence of nuclear weapons not only ensured that they were never used, but also helped stop hostile actions. In the post-Cold War world, deterrence has grown to encompass more than just nuclear deterrence. Non-military deterrence is an important part of modern foreign policy. The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) and the US have used rhetoric, sanctions, cyber threats and collective security as deterrence tools. While the history of deterrence is muddled with successes and failures, recently, it has been ineffective for the United States. Despite its immense military power, mistakes made in Syria and North Korea have hindered America’s potential to successfully deter hostile actions from other states.

In order to successfully deter a foreign state from taking action, the state must believe that the deterring nation’s threats are credible. Without this credibility, there is no incentive for a country to refrain from acting against the red lines imposed by the deterring nation. Recently, American foreign policy mistakes have decreased its credibility to the world. Two important cases have been Barack Obama’s red line in Syria and Donald Trump’s rhetoric toward North Korea.

In 2012, Obama proclaimed that if Bashar al-Assad’s regime used chemical weapons, it would “cross a red line”and lead to US military intervention. Then, one year later in 2013, more than 1400 Syrian citizens were killed in a chemical weapon attack. Rather than opting for military action, the US elected to work with Russia in a deal to attempt to dismantle Syrian chemical weapons. Yet, Syrian chemical weapons attacks have persisted as recently as April. Perhaps if the Obama administration had followed through on its promise of military intervention, Bashar al-Assad would not have used chemical weapons again. While a diplomatic solution is almost always preferable, it does not have the same powerful deterrence effect as a military intervention. When Bashar al-Assad considered deploying chemical weapons again, the threat of the US and Russia dismantling more chemical weapons was insufficient to deter him. It is impossible to argue whether or not military action would have led to a completely different outcome four years later. However, America’s failure to follow through on its red line threats has diminished its credibility to the world. If the US cannot be counted on to follow through on threats, its enemies will have no incentive to listen.

President Donald Trump’s administration has exacerbated America’s deterrence problems. On August 8th, Trump said that any more threats by North Korea to the United States would be met by “fire and fury“. The next day, the Korean Central News Agency said that the North was “seriously examining” a strike against Guam. Then, on August 30th, North Korea threatened Guam again, saying that their latest missile was a “meaningful prelude to containing Guam“. Although North Korea clearly crossed Donald Trump’s red line, they were not met with “fire and fury”. To Trump’s credit, a response of “fire and fury” would have led to considerable casualties, which he sought to avoid. Why, then, did President Trump make this threat? The empty threat eventually only decreased American credibility. If North Korea crosses red lines without being subjected to the American threats, why would it abide by future red lines? Much like Barack Obama’s red line in Syria, President Trump’s recent red line served only to decrease the credibility of future American threats.

The conventional rhetorical response to North Korea is that an attack on an ally will lead to an “overwhelming” military response from the United States. A military response to a North Korean attack is a successful deterrent only if it is believable. The problem with Trump’s strong language is that North Korea doesn’t believe it. Donald Trump’s and the United States’ credibility is so low that North Korea has repeatedly called his bluffs. Trump’s language has not only failed to deter North Korea but has also led to an escalation. In addition to threats of “fire and fury”, President Trump also threatened to “totally destroy” North Korea, which, in turn, perceived the US head of state’s words as a “declaration of war“. Rather than diffusing and deterring, Trump’s rhetoric has compounded the problem, thereby thrusting the world into a precarious situation. Tensions between the US and North Korea are higher than usual and a miscalculation could have terrible consequences.

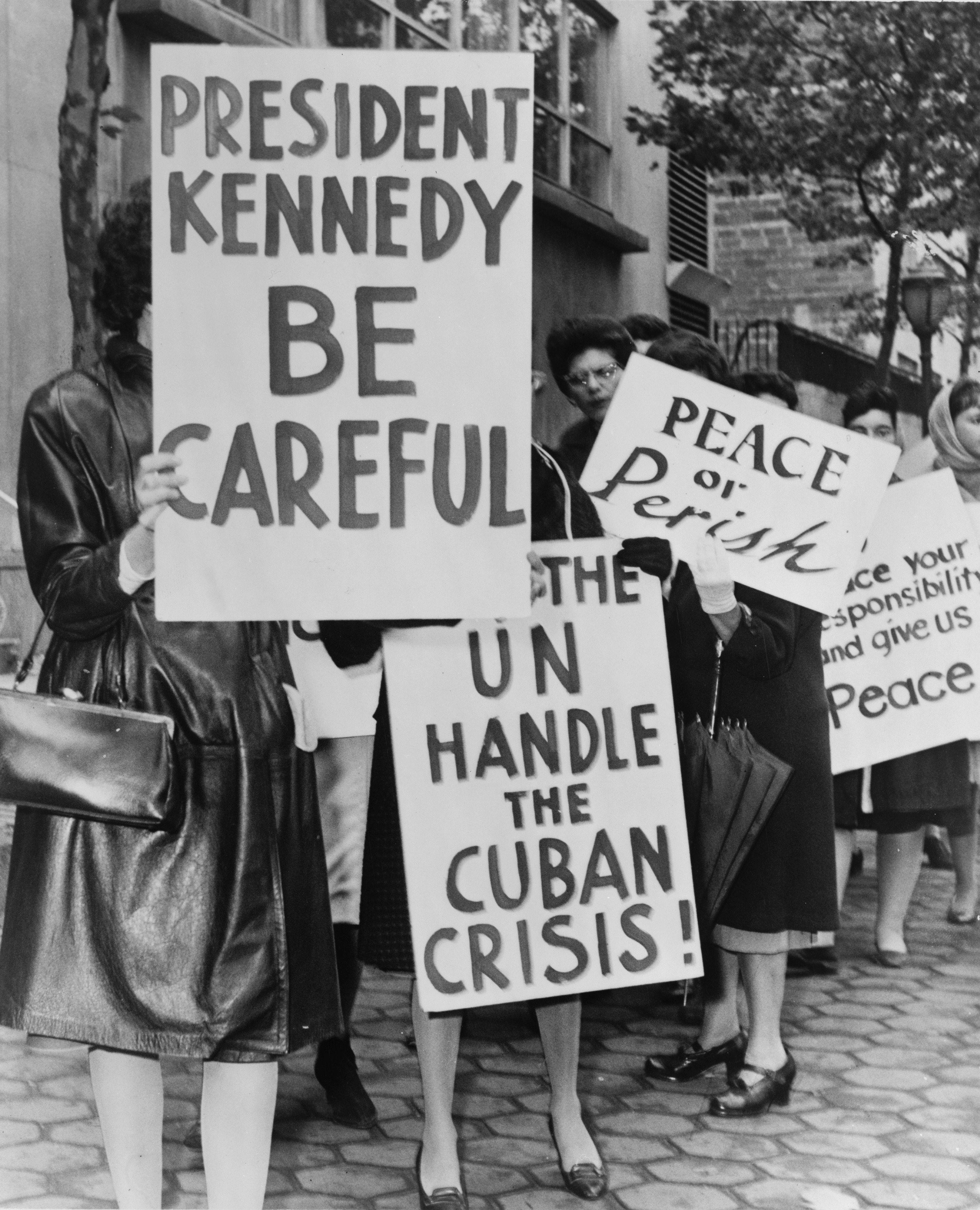

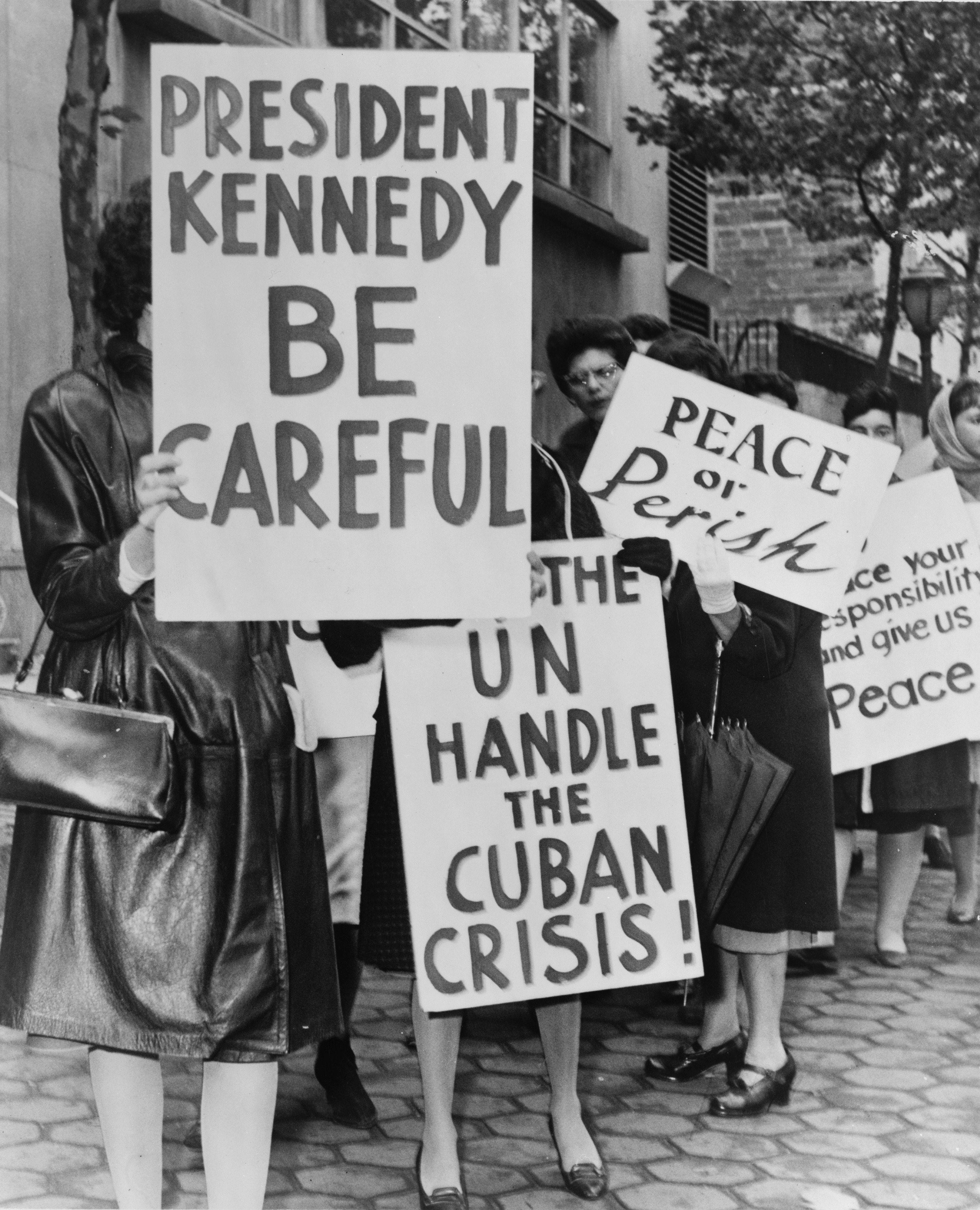

https://flic.kr/p/fqtn59

Another worrying statement from President Trump occurred when he labeled Kim Jong Un a “Rocket Man” on a “suicide mission“. Is Trump arguing that Kim Jong Un is irrational, making deterrence impossible? H.R McMaster, his national security adviser noted that “classic deterrence theory” did not apply to Kim Jong Un. The idea that Kim Jong Un is irrational is a popular, but ultimately false notion. The North Korean president wants nuclear weapons solely because he is concerned with regime survival. If Kim Jong Un has nuclear weapons, it becomes near impossible for any external power to overthrow his dictatorship.

A North Korea that possesses nuclear weapons is one that is hard to touch through a military option. As military interventions in North Korea and across the world become increasingly unlikely due to nuclear weapons, the world must fall on deterrence and diplomacy to promote peace. American deterrence policy must be a strong example to the rest of the world. It is crucial that America rebuild its credibility, in order to reassure its allies and deter its enemies. A smarter deterrence policy involves carefully chosen rhetoric and actions, in addition to credibility and efficacy once red lines are crossed. However, deterrence alone is insufficient if the world’s foremost policeman is to combat all of its foreign policy challenges. Sanctions, tough talk, and military shows of force are alluring displays of hard power, but prior to such means, all channels of diplomacy should be exhausted. Successfully deterring North Korea is vital but a world in which North Korea doesn’t need to be deterred is even better. Improving US deterrence policy is crucial, but it is important to note that, sometimes, the best weapon doesn’t shoot.

Edited by Luca Loggia