A Look Back at the Lasting Impact of George H. W. Bush’s Invasion of Panama

President George H. W. Bush passed away in November at the age of 94. While his time as president was a short 4-year term in the early 1990s, his foreign policy legacy maintained its relevance for years afterward. This is especially true when looking at the 1989 US invasion of Panama. While immediately inconsequential beyond the borders of the small Central American country, the invasion marked the beginning of a new direction in American foreign policy.

During the Cold War, the United States developed many relationships of convenience with authoritarian regimes and dictatorships throughout the developing world. The US supported the brutally repressive Pinochet regime in Chile for as long as it could and propped up many others of his ilk to grow the amount of friendly anti-communist regimes. But with the Soviet Union crumbling by 1989, that threat which had once dominated American security concerns dissipated. As a result, many of these regimes which the United States had tolerated for years became challenges for the new single global leader to contend with.

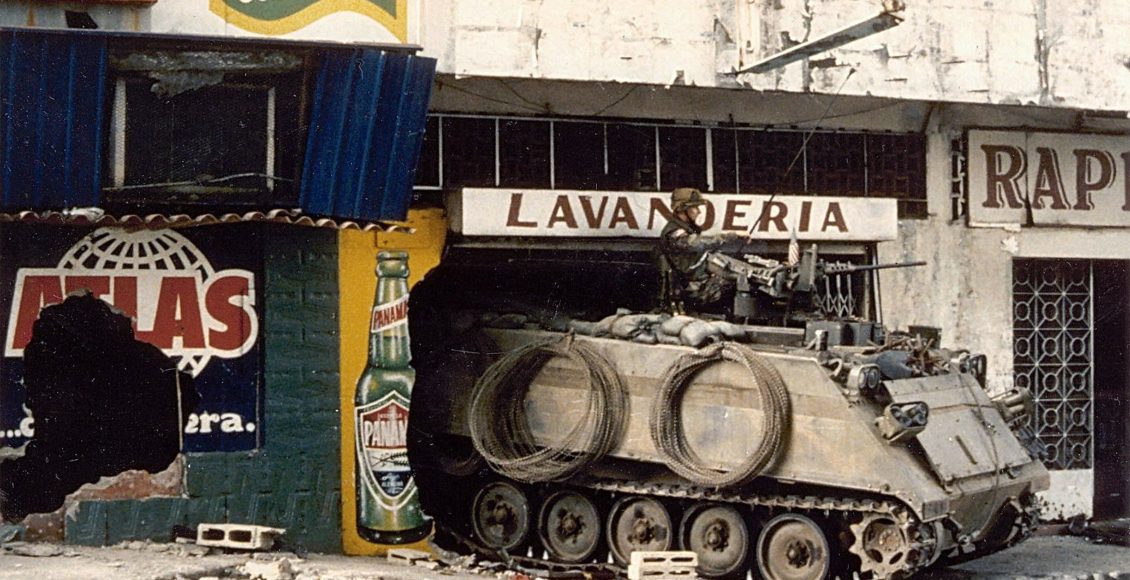

The invasion of Panama in 1989 provides an excellent example of this transformation that occurred under President Bush. The American relationship with the Panamanian regime during the Cold War was not its most consequential, but nonetheless Panama would mark a change in American foreign policy that persisted for years. General Noriega, The Leader of Panama at the time who was once a CIA payee, became a new target of American aggression after the sharp turn in American attitude toward many of its former autocratic allies. He was a major drug trafficker and a repressive leader, making him an easy target for a US executive without a legitimate opponent for the first time since before the Second World War. In December 1989, Bush sent about 26,000 troops to conduct what was essentially an arrest and extraction of Noriega, who was brought back to the United States and imprisoned.

However, the invasion also resulted in the death of about 3,000 Panamanians and caused lasting damage to the small Latin American country. In December, the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights concluded that the invasion failed to adequately prevent civilian harm, and placed responsibility on the United States for violating rights to life, integrity, and security of the many injured and deceased in the invasion.

While Panama itself never had any remarkable impacts on American interests or security, the Invasion of Panama is significant because it was the first major American foreign policy move after the fall of the Berlin Wall, which had occurred just weeks prior. The invasion represented a turn away from a foreign policy emphasizing national security in relation to Soviet threats which had dominated the Cold War. Bush’s invasion of Panama marked the start of a pattern of American intervention characterized by failed democratization attempts and American exceptionalism.

The invasion in Panama ushered in a new era of foreign policy which would endure through the 2003 invasion of Iraq. Bush claimed that the Panamanian invasion had been in the name of promoting democracy and removing a regime which was involved in the drug trade. In the ensuing years, Panama would not be the only country to experience pressure from the United States to democratize. According to Bush, the US was continuing the wave of democratization that had already begun sweeping Eastern Europe. Noriega, or any other autocrat, would be simply pushed off the path if they stood in its way (even if they had previously been backed by the United States). This would be how the United States justified military action.

After Panama, and somewhat because of Panama, spreading the ideal of democracy became a fundamental commitment of the Bush administration and the administrations that followed. The use of force made the ordeal quick, efficient, and precise; and the positive lessons learned in Panama about the use of force were still lingering in 2003 when the American foreign policy executive decided to invade Iraq. Back in 1989, the US was able to step into Panama and very efficiently complete its objectives without the help or the support of the international community. So in 2003, using the same approach that had been set at precedent by Bush Sr. in Panama, George W. Bush invaded Iraq. In Iraq, somewhat like in Panama, the export democracy was far from a resounding success. After ousting Noriega and establishing the democratically elected government of Guillermo Endara, drug trafficking and corruption problems were no better than before the invasion. Similarly, after the 2003 invasion in Iraq, where the United States removed the murderous regime of Saddam Hussein, the US set up a perfunctory replacement democracy. In Iraq, democracy failed more miserably than in Panama, since the absence of Saddam Hussein’s ruthless stability led to deepening sectarian divisions and made room for ISIS to grow. In these cases, American moralistic intervention in the name of democratization, which began post-Cold War in Panama, failed to produce the intended changes.

Looking back, while moralism as a justification for military engagement after the Cold War began as an observable trend in Panama, ironically the promotion of democracy as the motivator is very difficult to apply to the Invasion of Panama. As the invasion set forth, the sheer force with which the United States imposed its will makes it clear that promoting the establishment of a stable democratic regime in the interest of Panamanians could have been at best a secondary goal. The US military’s indiscriminate bombing of civilians and the 442 explosions set off in the first 12 hours can attest to the lack of concern accorded to the Panamanians who Bush claimed to be liberating. And this is seconded by the fact that Dick Cheney, Secretary of Defense at the time, emphasized only a couple of months before the invasion that the United States was not there to remake the Panamanian government and that any sort of action resembling an invasion would come with outrage from the international community – so an invasion would be a course of action best avoided. Lastly, the US administration had been aware of Noriega’s involvement in drug trafficking and corruption well before the Panamanian leader became a target, so it certainly was not the revelation of this information which spurred the invasion. Given these circumstances, it seems hard to imagine that Bush’s claims about the invasion being in the interest of democratic transition could be wholly true.

Instead, it appears that the American Invasion of Panama was an opportunity to reaffirm the US’ status as the single superpower. Panama offered a display of military efficiency and strategic superiority, and little to do with democratization; even though the event itself may have shaped the following years of democracy promotion in Latin America and the Middle East.

Edited by Catharina O’Donnell