A Tenuous Peace: The Danger of the Northern Ireland Protocol

The peace that holds the six counties of Northern Ireland together is a delicate one. Forged by the 1998 “Good Friday Agreement,” the state is still fraught by the legacy of a decades-long conflict between Protestant unionists and Catholic Republicans known as “the Troubles.” Today, in the wake of the UK’s departure from the EU, the divisions of Northern Ireland are threatening to reemerge in full force.

2021 marks 100 years since the island was partitioned into the independent Republic of Ireland and the loyalist stronghold of Northern Ireland. In many ways, the “Troubles” started with this partitioning. In his book “Biting at the Grave,” Irish Historian Padraig O’Malley describes the creation of Northern Ireland as a sort of ‘bastard begetting’: “Northern Ireland came into being because no one wanted it. Protestants did not want it — they sought only to preserve the union of Ireland with Britain.” In contrast, the Catholics wanted a united Ireland; the exclusion of the six counties from the Republic stood as a testament to both their inability to achieve that and the continued imperial domination of the British Crown.

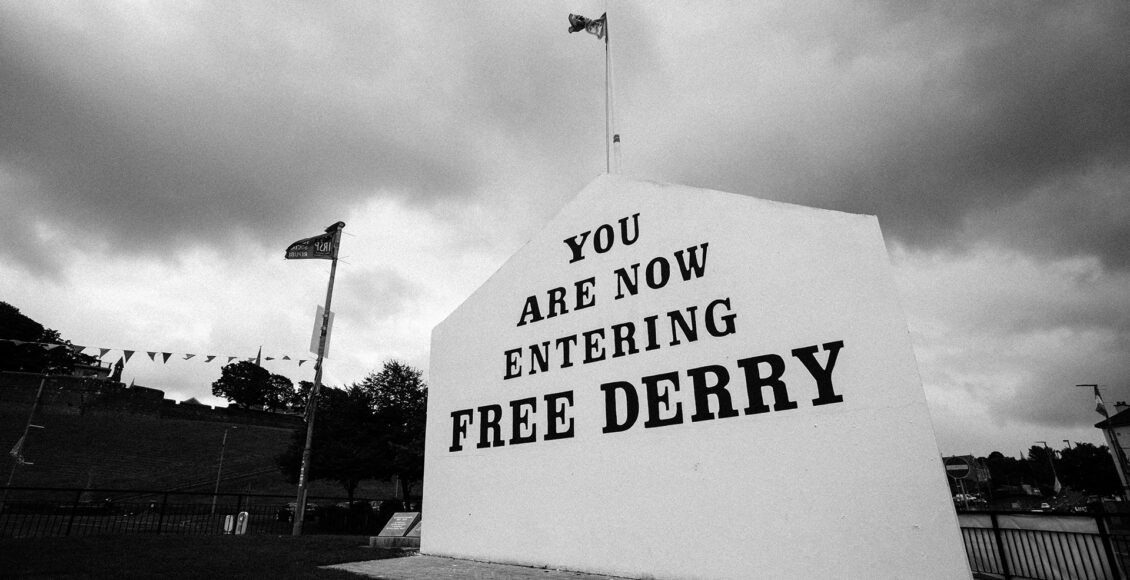

When speaking of the Troubles, it is easy to reduce the conflict to pure sectarianism: Catholic minority versus Protestant majority. Though it did have sectarian overtones, the Troubles were, at their core, a political conflict. Specifically, Northern Ireland was destabilized by violence between Loyalists, who wanted to remain a part of the United Kingdom, and Nationalists, who fought for a united Ireland. After partition in 1921, The Loyalist (mostly Protestant) majority in the six counties began a pattern of anti-Catholic discrimination culminating in the outbreak of violence in the late 1960s. In that decade, the Catholic community of Northern Ireland became increasingly vocal regarding their desire for political equality. Specifically, Northern Irish Catholics weren’t present at Stormont (the parliament) and were kept out of many jobs and areas by the Protestant majority. The state responded with brutal force; in response to violent state repression, the Provisional Irish Republican Army (Provos, an offshoot of the Irish Republican Army) gained support among the Catholic community. In 1969, a riot in the Bogside neighbourhood of Londonderry (or Derry) sparked violence throughout the six counties, and the British Army was called in to quell the fighting. In the summer of 1970, in response to paramilitary violence by both the Provos IRA and the UDF (Ulster Defence Force), the “British Army changed its policy and role to one of counter-insurgency or counter-terror.” The violence escalated throughout the next decade, with the British Army coming to be seen by many on the Republican side as an extension of the Ulster Defence paramilitary groups. In 1972, the British Army murdered 14 Catholic civilians during a protest against internment without trial. This event, which came to be known as “Bloody Sunday,” galvanized the republican cause and resulted in a surge of support for the Provos IRA. Republicans, Loyalists, and the British Army continued to terrorize the country for 30 years.

By the time the Good Friday Agreement — a peace agreement between the UK and the Republic of Ireland — was signed in 1998, more than 3,500 people were dead. The cities of Northern Ireland were carved up by “Peace Walls” that still separate Catholic and Protestant neighbourhoods. The living memory of the Troubles is inescapable in Northern Ireland — it is literally painted on the walls of buildings in the form of murals commemorating the heroes and the dead of each side. It is this living memory, combined with Northern Ireland’s still-divided national identity, that makes peace in the country so tenuous. Much of that peace is predicated on the invisible border between Northern Ireland and the Republic, an achievement of the Good Friday Agreement. This invisible border means that people and goods can flow through without a second glance. A result of Brexit, however, is that goods from the UK can no longer enter the EU as simply. Instead, they must be cleared through customs. To install customs agents on the border between the North and the Republic is to acknowledge that that border exists at all and could cause the combatants of the Troubles to pick up their weapons and once more divide the country along bloody lines.

In order to avoid this, the EU and UK have instead negotiated the “Northern Ireland Protocol,” which avoids customs on the island and instead places them in the Irish Sea. In creating this protocol, attention has been paid to respecting the Good Friday Agreement (GFA) terms. Specifically, the protocol is stated to be “without prejudice to the provisions of the [GFA],” and Article 1(3) tells us that the Protocol “sets out arrangements necessary […] to protect the [GFA] in all its dimensions.” In practical terms, under the protocol, goods will not be checked between Northern Ireland and the Republic but instead between Northern Ireland and the rest of the UK. To many unionists, who make up about 42 percent of the population, this policy is essentially a show of the UK’s disregard for them and their national identity as citizens of the UK. Though it is difficult to say what percentage of the population they represent, a vocal faction of the group feels as though they are being severed from the UK against their will. In April 2021, tensions regarding the “Northern Ireland Protocol” ignited in Belfast. A bus on the Shankill Road — a main thoroughfare of the protestant area of Belfast — was set on fire. Similar violence was reported in Belfast and other Northern Irish urban centres, notably the city of Derry, for several consecutive nights and 41 police officers were injured. Though there has been little reoccurrence of this violence in the months since then, the Northern Ireland Protocol is still being contested, and the tension has not disappeared. The legacy of the troubles is clearly seen in the controversy around Northern Ireland, especially in the unwillingness of the UK to provoke the republican factions by pushing the Good Friday Agreement even slightly. Rather than protect the peace, however, this careful attention to the 1998 agreement has inflamed the tensions in the country, and it remains possible that the mishandling of the Northern Ireland Protocol going forward could plunge Northern Ireland back into a level of political violence.

Featured Image: Free Derry Corner by John Twohig. Licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Edited by Ewan Halliday