Algeria’s Mass Protests: A Rare Momentum for Algerians

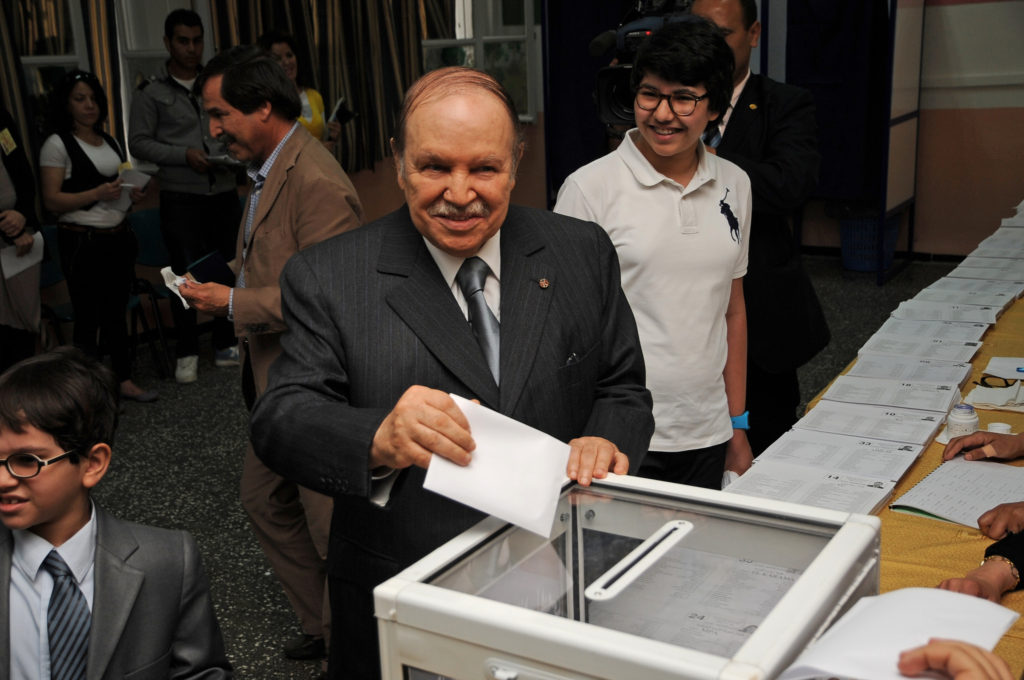

President of Algeria, Abdelaziz Bouteflika https://bit.ly/2BVNgUR

President of Algeria, Abdelaziz Bouteflika https://bit.ly/2BVNgUR

It is the candidacy that broke the camel’s back, many observing the recent protests against Algeria’s ailing President Abdelaziz Bouteflika’s candidacy for a fifth term would say. The physical incapacity of Bouteflika to exercise his presidential duties is best exemplified by his absence in meetings and his representation by a portrait of him that receives all the honors. At 81 years old, his obstinate refusal to cede power despite a long battle with illness fails to be understood by the Algerian population. His longstanding rule is attributed to the opacity of Algerian politics and the electoral process which obstruct alternate successions. Under these conditions, the streets seem to be the only resort for Algerians.

After 20 years of Bouteflika’s rule, one might dismiss this awakening as nothing short of ordinary and predictable. But the recent wave of Algerian protests have much to surprise the international community and observers of Algerian politics: it is the first time, since the Arab Spring uprisings in Algeria failed to materialize in 2011, that Algerians simultaneously take to the streets in multiple regions to contest the long-drawn-out rule. Algiers, where protests are illegal since 2001, and where the police tends to intervene on the spot to contain the slightest attempt to gather, has witnessed its most important protests since Algeria’s Black Spring in 2001.

Amid a heavy police presence, tens of thousands of people took to the streets last Friday in Algier’s May 1 Square and other Algerian cities to protest a re-election bid by Algeria’s longest-serving president. Rallies were a response to social media calls by activists for nationwide protests on Friday after the weekly Muslim prayers, mostly by partisans of the movement Mouwatana, composed of intellectuals from opposition parties and activists. More than 40 people were arrested in the protests, said the authorities, and police fired tear gas to block a protest march on the presidential palace. In response, demonstrators threw stones. But despite the arrests, the authorities largely tolerated the protests around the country, considering the strict ban on demonstrations in the capital since 2001.

In parallel, many hundreds of protesters gathered in Paris, in the Republic Square, to reject Bouteflika’s candidacy for a fifth term. At the foot of the monument celebrating the Republic, an immense picture of the President was hanged, barred by the now-viral «Non au 5e mandat!» slogan. Gatherings were also held in Montreal last Sunday, in front of the Consulate General of Algeria, where more than 1500 people showed up.

Protests in the capital and other cities have proved relentless for the past five days, with Sunday’s protests met with tear gas from the police to disperse the crowd. Hundreds of people gathered in downtown Algiers to protest against a fifth mandate for Bouteflika . Tuesday’s rallies were led by university students, as tens of thousands of students embarked into the growing nationwide protest movement. Large banners could read “Not in my name“, after 11 student unions voiced support for Bouteflika’s rule.

Elected for the first time in 1999, Bouteflika was constantly reelected since 2004. In office for 20 years, he has rarely been seen in public since he suffered a stroke in 2013, and last publicly addressed his nation in 2014 after his re-election for a fourth term. His opponents and multiple analysts have questioned his fitness to stay in power and claim his deteriorating health condition preclude him from carrying on his presidential duties.

Confined to a wheelchair, he repeatedly cancels official meetings. In December, he was unable to meet with Saudi Crown Prince Mohammad bin Salman in Algiers for a two-day visit due to a flu. The last time he met with a senior foreign official was during a visit by German Chancellor Angela Merkel on September 17, albeit former canceled meetings with both Merkel and Italian Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte. On Thursday the 21st, as nationwide protests were anticipated the following day, the president’s office announced that Bouteflika would head to Geneva on Sunday February 24th for ‘‘routine medical checks’’ – only ten days after a previous treatment in Switzerland. A veteran of Algeria’s independence struggle, Bouteflika is fighting a protracted battle with illness and has repeatedly flown to France for treatment.

On February 10, Bouteflika announced his intention to run for a fifth term in the North African country’s presidential elections scheduled for April 18, expressing an ‘‘unwavering desire to serve’’ despite acknowledging his health problems. The message came in a statement from Bouteflika to the nation by state media APS, following his endorsement by his party and the ruling coalition. ‘‘We have chosen him because we need continuity and stability’’, declared party leader Moad Bouchareb in front of around 2,000 supporters at a sports stadium in Algiers for a pre-campaign meeting. Several political parties, trade unions and business organizations have already declared their support for his re-election.

But despite the political class’s attempts at reassuring citizens, the mass demonstrations show that Algerians can no longer be fooled. After 20 years of Bouteflika’s rule, there is an increasing feeling among the Algerian population that the status quo can no longer hold. ‘‘We are fed up’’, chanted the crowd, along with other sharp-cutting slogans. While strikes and protests over social and economic grievances are nothing new for Algerians, they are usually not spread over the country and do not hinge on national politics. This time, it would seem, decades of contained silence due to social despair and the dread of returning to the violence of the 1990’s, long deemed a factor of Algeria’s inoculation against the Arab Spring, have set the stage for rising frustration over the country’s soaring living conditions and political crisis.

Despite improving economy over the past year as oil and gas revenues have increased and austerity measures were eased, the state has not been able to improve citizens’ purchasing power and provide work for a large number of the unemployed youth. Long credited for ending a civil war by offering amnesty to Islamist fighters, Bouteflika’s popularity is trivial among young people, most of which feel disconnected from a political elite class constituted of veteran fighters from the 1954-1962 independence war with France which have governed Algeria ever since. Almost 45% of the North African country’s population is aged under 25. A sense of social impotence looms over the youth due to a widespread knowledge that social and relational capital often trump academic efforts, a phenomenon Algerians infamously refer to as ‘‘Le piston’’. Official figures do little to ease this despair: more than a quarter of Algerians under 30 are unemployed. For many Algerians, leaving the country to seek better wages and living conditions remains more promising than casting their vote.

Algerian politics is notoriously opaque, with a designated term, ‘‘Le pouvoir’’, referring to the shadowy political elite of senior generals and others within the regime. Members of the President’s close circle, the President’s brother and senior aide, Saeed Bouteflika, and the General Ahmed Gaid Salah, chief of staff in the National People’s Army, are suspected to be Algeria’s de facto rulers and to be ruling in the President’s name since his choke, which severely impaired his speech. While the army and old guard remain powerful, it is unclear which actor in Algerian politics holds how much power. Opponents to the current regime point to its authoritarian nature and to a civil-military oligarchy cemented by corruption.

The stakes are high for Algeria’s political class. At the time of the Arab Spring, Bouteflika’s government was able to contain the uprising and avoid the major political upheaval as seen in many other Arab states with promises of reform and pay raises financed by the country’s revenues from oil and gas. But the growth of population and simultaneous decline in economic resources have made social peace more difficult to purchase. Not only that – the protests are more fierce this time around. It may very well be that Bouteflika’s re-election only provided the ruling FLN (or National Liberation Front) and the powerful army with short-term stability and additional time under the spotlight before an eventual difficult succession.

As the rest of the tale has yet to be written, one can only wonder if it will be written by the same old political elite or by Algerians themselves. So far, Algeria’s future remains opaque and unpredictable. As Algeria’s political and media landscape obstruct the emergence of new political personalities or groups, Bouteflika’s victory in the upcoming presidential elections should not come as a surprise to anybody familiar with Algerian politics. Further, the opposition remains weak and divided, as leaders from the country’s diverse opposition parties failed to agree on a joint presidential candidate last Wednesday, and oscillate between boycotting the election or agreeing on a candidate.

Against that backdrop, a transformation of the system of governance seems unlikely. But the current momentum nonetheless constitutes a rare opportunity for Algerians to turn the tide in their favor and make history. The force ratio between the supporters of a fifth mandate and its opponents seems to be overturned, as the presidential clan struggles to mobilize real popular support faced with the unprecedented level of dissent. It might finally be time to contemplate a post-Bouteflika era – whatever it may hold for Algerians.

Edited by John Weston