American Indifference Is Not a Work of Fiction

Filming of The Handmaid's Tale at the Lincoln Memorial

Filming of The Handmaid's Tale at the Lincoln Memorial

In 2017, a new edition of The Handmaid’s Tale was released — with a twist. Margaret Atwood included in this version a newly-penned introduction referencing the novel’s relevance in the Trump era. This decision was heavily influenced by the 200 per cent increase in sales the novel saw when Donald Trump was elected to office in 2016. The book, which now includes a sequel released 2019, and a television adaptation on Hulu, follows the journey of a woman called Offred as she seeks to escape a dystopia governed by American religious extremists. Atwood uses a temporal division of night and day as a device to show how Offred is effectively “waking up” to a world she no longer recognizes. Though the show and many interpretations of the story emphasize its violence and social terror, it is this personal struggle that reveals how the true enemy of The Handmaid’s Tale is a culture of complacency that allows extremism to emerge and persist.

Since its publication in 1985, the novel has been an inspiration for women’s rights activists. The popularity of the Hulu series has only increased the frequency of The Handmaid’s Tale imagery in public protests. The story is frequently compared to developments in American politics, and the advertisements for the third season of the television series were no exception: a commercial that ran during the 2019 Super Bowl parodied an ad from the Reagan presidency, which is interrupted to reveal the horrors that await viewers in the new instalment of the show. Beckoning to the Reagan era’s conservatism as it finds parallels in the series and the current presidential administration, the ad also reveals how the action and subtlety of the series have become inversely proportional.

In order to market The Handmaid’s Tale for television, the series required an approach that highlighted the story’s brutality over its civic concerns. While this may be more exciting for viewers, the show has also garnered criticism for hyperbolizing oppression. For The Guardian, Atwood wrote that a key aspect of the story ends with hope, as it would be unfitting to call readers to action through only negative means: “When asked whether The Handmaid’s Tale is about to “come true,” I remind myself that there are two futures in the book, and that if the first one comes true, the second one may do so also.”

To this end, the television adaptation forgets that the driving forces of change are the ability and will to enact it. Creative decisions for the show may well be made in the interest of extending the program’s running time, but The Handmaid’s Tale extends the story at a cost. It perpetuates patterns of social apathy as Offred, the leader of a burgeoning revolution, chooses to stay within her system of oppression. A series that criticizes its government in comparison to American leaders without a satisfactory response to them loses any force that could be found in a call to involvement in real-world politics. It instead profits on political fears alone.

The eerie comparisons of The Handmaid’s Tale also extend to a different interpretation of political fear, where citizens struggle to see past the discourse of shock-value headlines. In the novel, Atwood writes: “Whatever is going on is as usual. Even this is as usual, now. We lived, as usual, by ignoring. Ignoring isn’t the same as ignorance, you have to work at it […] The newspaper stories were like dreams to us, bad dreams dreamt by others. How awful, we would say, and they were, but they were awful without being believable. They were too melodramatic, they had a dimension that was not the dimension of our lives.”

However, within the realm of US politics, the use of social media has been breaking through an aspect of this apathy. Efforts such as the Lincoln Project are successful in consistently generating media buzz around what they believe candidate policies should look like and how voters should react. For example, following a report from The Atlantic asserting that Trump had been disrespecting the service of veterans, the Project called on its Twitter followers to post #WeRespectVets — within an hour, it became the most popular politics topic on the platform.

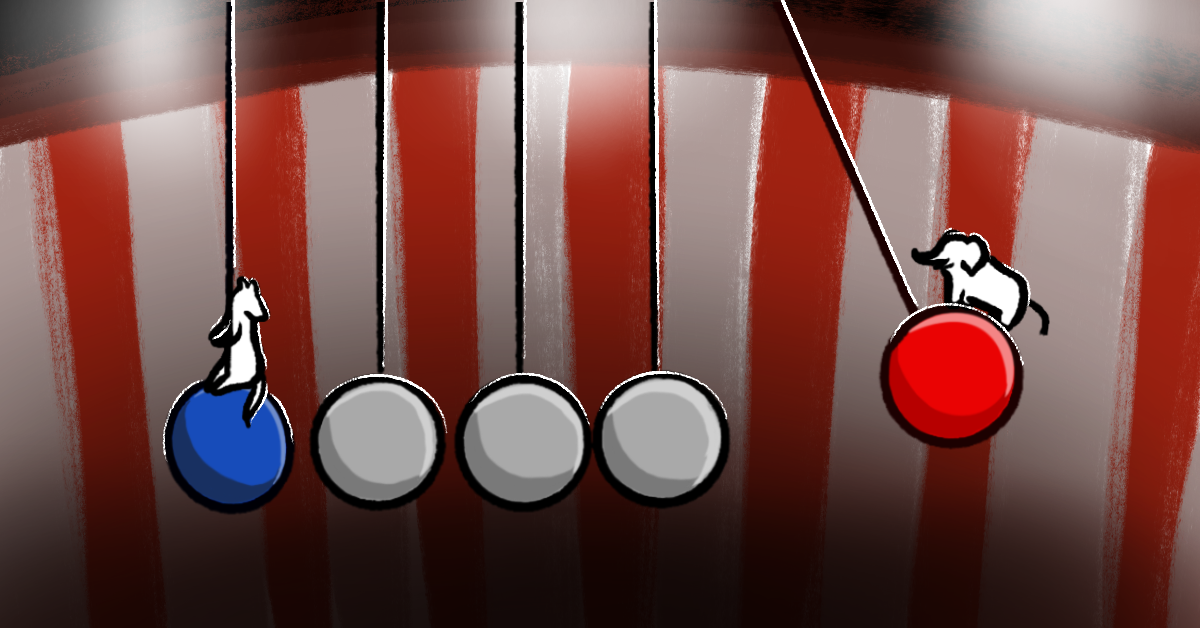

While the Lincoln Project is able to add a level of relevance to political developments, their reach seldom extends past Twitter’s primary demographic of millennials, most of which have already made their voting decision. Throughout the election and the Trump presidency, social media has been a hotspot for slander and political arguments, fostering partisan animosity that makes it increasingly difficult to hear beyond a given circle’s ‘popular opinion’. Voters beyond the 22 per cent on Twitter, if they are not following the election too closely, are likely to be bottlenecked into their closest side of the aisle amidst rising tension. As FiveThirtyEight points out, the conflict extension of each party coupled with partisan stereotyping furthers a vision in American politics of “us” and “them”. In this growing division, reliance on a pendulum of left and right-wing presidencies pushes voters to compromise for the maintenance of a fraught structure.

The rise of this pronounced willingness to compromise challenges the idea of requiring a leader voters can support. Rather, many who settle do so in hopes that their vote is truly “what Bernie would have wanted,” or conversely, a vote that avoids the extension of an “un-American presidency.” The behaviour of a population that votes begrudgingly plays into the same marketing structure of assimilation, where what unifies a party is often only its fear of the other whether it be through “Settle for Biden” or other means.

In The Handmaid’s Tale, the fear of the “other” has been hyperbolized to create an image of America that has gone too far. However, as the narrative alternates between the present and semblances of the past, it reminds us that Offred is apathetic to the world around her until the consequences of her passivity are realized. What is lost in the television adaptation of The Handmaid’s Tale is that which makes the original narrative’s message such a force in this political climate: the threat of public indifference is equal to that of ineffectual candidates. Atwood’s hope for change is not about the extraordinary circumstances of a revolution, or outstanding people who take charge, but rather about the significance of the everyday. It is how those circumstances, and those ordinary people can ignite change. America has already chosen its candidates, but the responsibility now falls to how they will raise up new ones. The answer to extremism is not found in extremism, it is found in steady action and attention to reality.

Featured image: “The Handmaid’s Tale” by Victoria Pickering is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Edited by Elizabeth Hurley