Brazil’s Chaotic Spectacle

While the Worker's Party under Lula was able to bring together an impressive coalition who all shared a common goal in creating a more equal society, Bolsonaro's base has no such unifying objective. Their aim was to topple the status quo, and now that that's been achieved, the veil has been lifted and the contradictions have been revealed.

Brazil's new President Jair Bolsonaro gestures after receiving the presidential sash from outgoing President Michel Temer at the Planalto Palace, in Brasilia, Brazil January 1, 2019. REUTERS/Sergio Moraes

Brazil's new President Jair Bolsonaro gestures after receiving the presidential sash from outgoing President Michel Temer at the Planalto Palace, in Brasilia, Brazil January 1, 2019. REUTERS/Sergio Moraes

Elected to office promising to bring unity to Brazil, Jair Bolsonaro has not delivered so far. Rather than providing the kind of stable, economy-minded administration that investors hoped for, Bolsonaro has instead presided over a government plagued by internal contradictions and very public disputes. The authoritarian culture warrior rhetoric of the President and his allies has not only drawn ire from left-wing Brazilians and the international community, but it has also angered many potential partners in Congress, impacting his ability to pass agenda items like pension reform, a highly important issue to investors. If Bolsonaro fails to please Congress and financial capital interests he may find his presidency on the ropes.

The Brazilian public is generally very charitable towards new presidents, giving them favourable ratings early on in their administrations. Lula had a positive approval rating of 43% in April 2003 (his first year as President), and only a 10% disapproval rating. Rousseff had even better numbers at that point in her term, with 47% approval and 7% disapproval. In contrast, Bolsonaro, coming off a resounding 55%-45% victory in the presidential elections last fall, has seen his approval rating fall to 32%, with 30% disapproval, by far the most unfavourable balance of any of the elected post-dictatorship presidents this far into their terms.

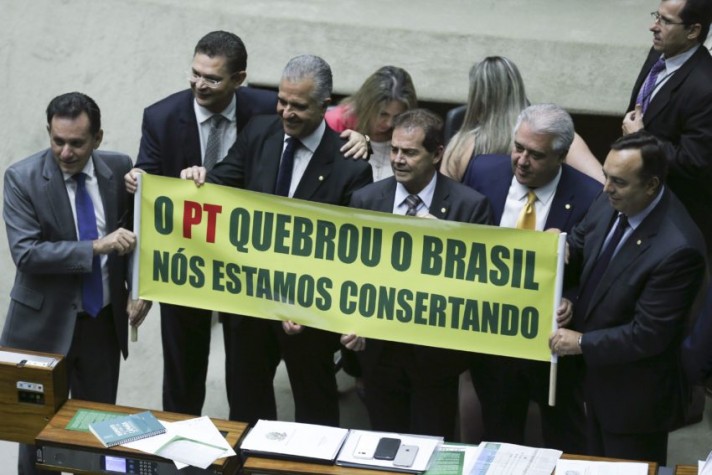

With an opposition fervently against him and everything he stands for, Bolsonaro must look to his allies to advance his agenda. On the face of it, it doesn’t seem like an overly difficult task. The right-wing parties “supporting” the government control 349 of the 513 seats in the Chamber of Deputies, making this the most right-wing Congress in Brazil’s post-dictatorship history. Unfortunately for Bolsonaro, these parties are united in a broad sense of opposition to the left-wing Workers’ Party (PT), and not much else. Among them are hardline neoliberals dedicated to market deregulation, social conservatives and evangelicals fighting against a supposed homosexual cultural Marxist agenda, security hawks determined to curb Brazil’s violence epidemic by giving free rein to the police and military to combat criminals, relative moderates like Vice President Hamilton Mourão, and of course corrupt gangsters with no coherent ideology whose only goal is to use public office to enrich themselves.

While the Worker’s Party under Lula was able to bring together an impressive coalition of unionists, Marxists, militants, liberation theologists, and more who all shared a common goal in creating a more equal society, Bolsonaro’s base has no such unifying objective. Their aim was to topple the status quo, and now that that’s been achieved, the veil has been lifted and the contradictions have been revealed. Just five months in, the battles are starting.

Mourão, for instance, was at the center of a contentious fight back in April between Bolsonaro and his son Carlos, who slammed the Vice President on Twitter, angering Bolsonaro. The fight culminated in Carlos allegedly seizing control of his father’s Twitter account for several days. The object of Carlos’ disagreement with Mourão and the “moderate” factions of Bolsonaro’s coalition is a man by the name of Olavo de Carvalho, a philosopher and astrologer residing in Virginia who many consider to be the “guru” behind Bolsonaro’s ideological vision. Unapologetically foul-mouthed, Carvalho is as Twitter-addicted as the Bolsonaro family, and frequently uses the platform to opine on topics of the day with characteristic abrasiveness. He opposes “cultural Marxism” and believes, among other things, that Pepsi is flavoured with aborted fetuses. Aside from the Bolsonaros, his disciples in the Brazilian government include Education Minister Abraham Weintraub and Foreign Affairs Minister Ernesto Araújo, who has alleged that climate change is a cultural Marxist plot. Carvalho’s detractors on the right worry that this kind of rhetoric, which has drawn ridicule at home and abroad, will harm their ability to advance their legislative program. He’s even disliked by some individuals on the far-right as well, including former Bolsonaro ally Alexandre Frota, an ex-porn star turned Congressman, who stated that half of Brazil’s problems could be solved if a missile was launched at Carvalho’s house.

In late May, more contradictions were revealed when Bolsonaro called on his supporters to protest against the Supreme Federal Court (STF) and Congress on May 26, as supposed retribution for thwarting his political agenda. His call produced another split in the government coalition, with senior right-wing figures like Speaker Rodrigo Maia denouncing the move. Maia has already come to blows with the government in recent weeks. The absurdity of the whole affair came to a fever pitch when angry Bolsonaro supporters denounced Kim Kataguiri, a newly-elected congressman and head of the far-right libertarian Free Brazil Movement, as a “communist” after he criticized the protest for being anti-democratic. To make matters more embarrassing for the government, Bolsonaro subsequently distanced himself from the demonstrations, and then reversed himself again, endorsing them but not actually showing up.

The more Bolsonaro antagonizes Maia and Congress, the more he puts his presidency at risk. With Rousseff’s impeachment, Congress proved they’re not above impeaching a President when they’re deemed no longer useful. Bolsonaro is no different. There are warning signs already—for the first time since 2016, Brazil’s economy shrank this past quarter. Pension reform is proving difficult, and Minister of the Economy Paulo Guedes has said he will resign if it doesn’t pass. Congress may find their jobs easier with Mourão as President, and Bolsonaro’s Social Liberal Party, which holds just 55 seats in the Chamber of Deputies, could find itself increasingly isolated.

Amid all this spectacle, however, it’s important to remember the serious harm this administration is doing, however incompetent they might be. While we laugh at Rio governor Wilson Witzel for falsely claiming that he attended Harvard on his CV, we have to remember his joyrides with the hyper-militarized police force, whom he has helped give free rein to abuse their powers. As fun as it can be to make fun of Minister for Human Rights, Family and Women Damares Alvez for her ludicrous religious beliefs, we have to keep in mind how dangerous her policies are for indigenous groups, women seeking access to abortion, and other marginalized communities. The whole world laughed at the spectacle of Donald Trump in the 2016 elections and at Tea Party figures in the years before that. Brazilians laughed at Bolsonaro too—for decades he was the laughing stock of Congress. Now they’re in power and are perfectly happy to watch us sit and laugh.

Bolsonaro the person may well be impeached or voted out of office in 2022, but the left doesn’t have a chance at combating the insidious forces that led to his election without serious organizing. Currently, Bolsonaro’s own coalition is a stronger opposition than the PT, who are largely content with scoring points and laughing at the spectacle. If they continue to fail to articulate a vision for the country that addresses inequality and violence they will continue to lose elections.

Edited by Shirley Wang.