Can We Separate Christmas from Consumerism?

The holiday season is upon us and many are eagerly awaiting and preparing for Christmas. My own fondest memories of Christmas as a child consist of decorating my house in November and compiling extensive wishlists to Santa of American Girl accessories and Playmobil toys. For many, the contemporary Christmas spirit is rather disconnected from the holiday’s religious purpose, which is to commemorate the birth of Jesus Christ. Instead, Christmas, the most magical time of the year, has become a time of over-eating, over-drinking, and over-spending on gifts in the name of family, charity, and gratitude. Christmas is often celebrated without religious connotations, and consumerism has become intrinsically tied with the holidays, as we fixate on finding the perfect gift for the brother-in-law we see once a year and stress about receiving yet another tacky Christmas sweater from Grandma. Advertisements exploit holiday nostalgia and joy to convince us we need the newest iPhone. This begs the question: can Christmas remain a meaningful celebration of Christian values, family, and joy while attached to consumerism and profit-making?

Commercialization of Christmas

Christmas sees consumerism heightened during the holidays, but the Christian religion paradoxically preaches against a preoccupation with materialistic possessions. To this end, gift-giving and Santa Claus became popularized in the face of growing secularization. As the religious aspect waned, Christmas was increasingly exploited for profit. This first became evident with the emergence of Christmas bonuses in the early 20th century, paralleled by the popularization of Santa Claus and the iconic “Yes, Virginia, There is a Santa Claus” response in the New York Sun newspaper in 1897. Bonuses encouraged gift-giving to loved ones, and more presents from Santa.

Rampant commercialism has become a shameless staple of American Thanksgiving, with gigantic Black Friday sales to kick off the holiday shopping season. Many shoppers line up for sales beginning at midnight, with deals often running laughably longer than just Friday, in the days and weeks leading up to and following Thanksgiving. In Canada, we see even bigger Boxing Day sales on the day after Christmas. After receiving gifts from friends and family, many seize the opportunity to buy even more! Throughout the holiday shopping season, the pressure to buy more and more is immense. From shopping mall Santas, to sentimental advertisements, to Christmas decorations, consumerism can be hard to escape, and nowhere is this more obvious than in the case of Santa Claus.

A Brief History of Santa Claus

Santa Claus is the premier gift-giver of Christmas, with unlimited resources, elf labour, and a workshop to fulfill the wishes of children well-behaved enough to make the “nice list.” Urban legend often credits Coca-Cola with the introduction of Santa Claus, but the beloved gift-giver has more complex historical roots. Santa Claus, also known as the holiday bearer of gifts Saint Nicholas, dates back to the fourth century Eastern Roman Empire, while Germanic pagan Yule traditions also mention a similar figure. Visits from Santa in their modern form were first invoked by writer Clement Moore, in his 1822 poem “An Account From the Visit of St. Nicholas,” later renamed and more famously known as “Twas the Night Before Christmas.” This poem embodied the anticipation for and wonder of Santa, his reindeer and his elves and, interestingly, had no references to nativity or the birth of Christ. It did, however, come at a time of rapid industrialization in the Western world when the economy needed people to consume more of the growing number of goods available. As a result of this concept of unlimited gift-giving from an omnipresent being, exchanging presents became central to the holidays, further propagated by Santa’s presence in advertising, as well as in the minds (and wishlists) of children.

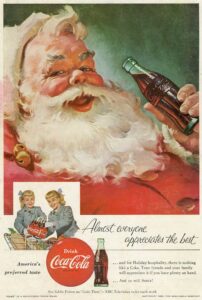

Santa Claus gained his characterization as we see him today in the late 1800s with drawings from Thomas Nast, also responsible for emblems like the Democratic Party’s donkey and Uncle Sam. It was then not until the 1930s that Coca-Cola used images of Santa in advertising to promote winter sales of the drink. Coal for naughty children came to be associated with Santa around the 19th and 20th centuries, when it was used to heat homes. More popularized now are figures like Mrs. Claus and reindeer, given their characterization in films like Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer and Elf. They have become ever-present symbols, connoting festivity and gift-giving, especially in advertisements.

Coca-Cola advertisement, featuring Santa Claus, published in 1955. “Coca-Cola” by twm1340 is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0.

The Role of Advertising and Social Class

Holiday sales covering celebrations from Christmas, to Hanukkah, to Kwanzaa make up 19 per cent of retail sales annually. As such, holiday advertising begins even before Thanksgiving. And with so many royalty-free symbols for brands to work with, including reindeers, chimneys, mistletoe, and Santa himself, ad campaigns are extensive and memorable. Faced with a troubling holiday season as the pandemic rages on, advertisers have acknowledged and actively incorporated the challenges of COVID into their branding strategies. This comes as one in four Americans report cutting holiday spending this year because of health measures and for financial security. With a global economic recession and people unable to see their loved ones, commercials are more representative of the times, many depicting smaller or virtual family gatherings. On November 12, Canadian Tire released an ad portraying a healthcare worker mother too busy to put up the Christmas tree with her eager son, who comes home from work to find he has fallen asleep stringing up Christmas lights around her room. Amazon put out a holiday ad titled “The Show Must Go On,” showcasing a young dancer whose performance is cancelled due to COVID. She goes on to lift the spirits of her community with a COVID-safe rooftop performance.

Sometimes the best gifts aren’t under the tree. Canadian Tire – Canada's Christmas Store. pic.twitter.com/XcyE2e1GNR

— Canadian Tire (@CanadianTire) November 13, 2020

According to a 2018 report by Chartered Professional Accountants of Canada, the average Canadian spends $643 on Christmas gifts annually. With all this spending comes the harsh reality that the holidays are not so merry for everyone. Visits from Santa propagate the idea that Christmas is inherently not commercial, as gifts are made in his workshop and given to children who are nice. This narrative is an advertiser’s dream but puts pressure on families to buy more. Credit counselling agencies see a 25 per cent increase in the number of consumers seeking help with debt in January and February. Christmas can be a very different experience for children from family to family, based on economic circumstances. The economic woes of many families during the COVID-19 pandemic is a reminder of how the commercialization of Christmas puts damaging economic pressure on the less fortunate of our societies.

Bringing the Family Together

The commercialization of Christmas is undeniable, and because of the profits to be made, it will almost certainly continue. Some claim this will wipe out the holiday’s true importance, while others argue it will save the tradition. As for Santa, with Christmas’ explicit purpose being to celebrate the birth of Jesus, Rev. Marcus Burch says Santa’s gift-giving reflects goodwill consistent with the values of Christianity (and perhaps society in general). Gift-giving after all is still just one element of Christmas. While it’s jolly to open advent calendars, shop for your loved ones, and receive beautiful gifts, in the midst of the holiday season and a deadly pandemic, take this holiday season to appreciate your family and friends, whether you are with them in person, or virtually.

Featured image: “… think I’ll keep this one!” by x-ray delta one is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

Edited by Max Clark