China’s Ambiguous Posture in the Arctic Region

The Royal Navy's Antarctic Survey Vessel HMS Endurance during her patrol of the Antarctic Peninsula early in 2007.

HMS Endurance is the Royal NavyÕs Ice Patrol ship whose function is to support British interests in Antarctic waters, especially around the Antarctic Peninsula. In addition she assists the British Antarctic Survey in carrying out its scientific research programs. She is fitted with modern hydrographic surveying equipment, which is put to good effect in waters which are still largely uncharted, and the data that is gathered is processed by the Hydrographic Office.

The Royal Navy's Antarctic Survey Vessel HMS Endurance during her patrol of the Antarctic Peninsula early in 2007.

HMS Endurance is the Royal NavyÕs Ice Patrol ship whose function is to support British interests in Antarctic waters, especially around the Antarctic Peninsula. In addition she assists the British Antarctic Survey in carrying out its scientific research programs. She is fitted with modern hydrographic surveying equipment, which is put to good effect in waters which are still largely uncharted, and the data that is gathered is processed by the Hydrographic Office.

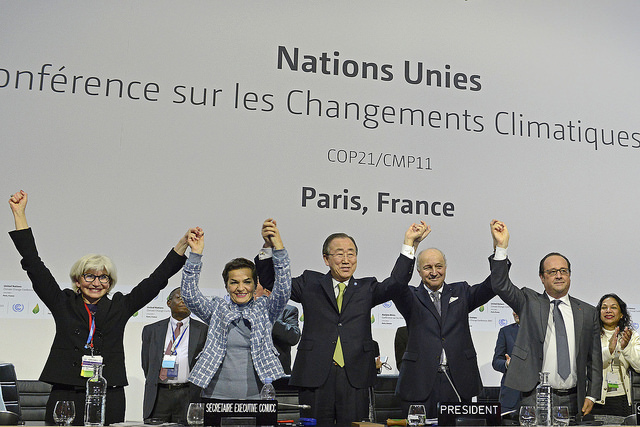

Thawing ice in the Arctic region has opened a path for considerable economic opportunities in terms of commercial routes and resource extraction. Unsurprisingly, geo-strategic interests have quickly stepped in. Arctic countries, namely the US, Canada, Iceland, Sweden, Finland, Norway, Denmark and Russia, have submitted their territorial claims to the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). These countries, along with six indigenous communities, also form the permanent members of the Arctic Council, an inter-governmental forum created to address regional issues. There are multiple questions that need to be addressed in the region such as research cooperation, environmental preservation, and legal territorial claims. In 2013, China, which considers itself as a “near-Arctic country,” gained the status of permanent observer at the Arctic Council. China’s recent release of a white paper on its Arctic policy makes its well-known interests official, but this highlights a conflict with its position as a global leader in the fight against climate change.

China has three related motives in mitigating global warming. First, there are considerable economic benefits to becoming a leader in clean technologies and “green” industrial development. Second, leading this fight paints a positive picture of China around the world, thus attenuating its aggressive stance on other issues. Third, environmental degradation is increasingly severe in China and threatens social stability, giving an impetus for the party-state to act. As a consequence, the country is taking the lead in the development of clean energy such as solar panels. While China produces about 24% of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions, it still has very low per-capita emissions figures. The country pledged to peak its carbon dioxide emissions by 2030 at the Paris Climate Accords and is on course to peak in 2027. Some analysts even argue that the country might do so before 2025.

In 2015, “China invested $102.9bn in renewable energy and installed half of the world’s new wind power” finds the Guardian. In 2016, Chinese state-related banks financed overseas coal projects that accounted for about “half of the foreign coal investment by G20 countries”. Yet, in the same year, China spent eight times that amount on renewable projects abroad. It is also implementing a domestic carbon market that should come into force in next year. The country seems serious in tackling climate change.

In its Arctic policy white paper, China commits to environmental protection and scientific exploration. China has engaged in an important polar research program that covers the study of interactions between the Ice Arctic Ocean, sea ice, and the atmosphere and how rising temperatures in the region affect climate in China. Scientific research efforts are one of the reasons why China earned the right to be a permanent observer in the Arctic Council. As part of these efforts, China has set up a research base and a satellite ground station in Northern Greenland, another research base on Norway’s Svalbard archipelago, and finally a research facility in Iceland. One could have thus expected China, as the European Parliament first did in 2008, to voice its support for an Arctic treaty similar to the Antarctic Treaty System. Such treaty would make the Arctic continent free from militarization and economic exploitation and a reserve for scientific research and cooperation.

Yet, environmental preservation in the Arctic appears to be a second-order priority for the Chinese party-state. In the white paper, the Chinese central government encourages, “its enterprises to engage in international cooperation on the exploration for and utilization of Arctic resources.” So far, Chinese economic operations in the Arctic have mostly been limited to two projects along Russian shores. China has also invested large amounts of money in Iceland after the financial crisis and is currently developing mining activities in Greenland. According to CBC, “Chinese state-owned firms have made tentative forays into Canadian mining.”

Further, China expects to take part in the development of shipping lanes, notably through the Northeast Passage. China has already adjusted its capacities for the Arctic: an icebreaking ship, the Xuelong, has already gone through the passage. Chinese Arctic tourism is also on the rise. The white paper also states that “the Arctic has the potential to become a new fishing ground in the future.” Given that China signed, along with other Arctic and “near-Arctic” countries, a legally-binding agreement not to engage in fishing operations in the high Arctic sea for the next sixteen years, China is playing the long-term game. Extractive activities, shipping lanes as well as mass fishing can hardly be seen as compatible with environmental protection in a region as sensitive as climate change as the Arctic.

CNBC rightly points to another contradiction of the publication: “China’s emphasized in the white paper that countries should respect ‘the rights and freedom of non-Arctic States to carry out activities in this region in accordance with the law,’ specifically pointing multiple times to the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea.” Yet, recent history shows China dismissing international law when it doesn’t suit its interests. In 2016, the Chinese party-state rejected the international ruling by the Permanent Court of Arbitration in the Hague over the legal basis of its claims on maritime territories zones that were disputed by the Philippines. Contradiction with Chinese characteristics.

Chinese Arctic policy is thus best understood through the lense of liberal environmentalism. The party-state isn’t making efforts to reduce its greenhouse gas emissions out of moral consideration for nature but rather in order to comfort its political legitimacy. China’s self-interested position on Arctic governance is in line with its leadership stance in combating climate change. The country seeks to be a leader in the fight against climate change but does so without compromising economic opportunities and economic growth. China, like many other Arctic countries, has never voiced its support for an Arctic treaty similar to the Protocol on Environmental Protection to the Antarctic Treaty signed in 1991. The future of environmental protection in the Arctic region is uncertain and will only depend on deals bargained between concerned governments such as the one preventing commercial fishing in international waters.

Edited by Marissa Fortune.