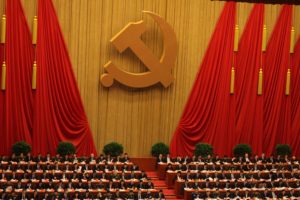

China’s New Totalitarianism

A totalitarian regime is defined as one that permits no individual freedom and seeks to subordinate all aspects of individual life into the authority of the state. When one thinks of such regimes, one typically harkens back to the governments of Nazi Germany or Soviet Russia, the original regimes for which the term was coined. If you were to try to think of a totalitarian regime today, North Korea is likely the first country which would come to mind. For many, the People’s Republic of China – its gargantuan neighbour – would rightly not figure into the equation. Liberalizing economically since the 1980s and having left the bloody purges of Mao well in the past, the conventional view of modern China is that of an authoritarian regime. A party dictatorship where the Communist party is the force to be reckoned with not a personalized dictatorship such as that of Mao or Stalin. However, recent shifts in internal power dynamics and new Orwellian policies point to a decidedly undemocratic shift. Similar to strongmen of the past, Xi Jinping’s new policies seem to reflect a desire not only to establish supreme control over his citizens politically but control their thoughts and actions as well.

Purges, Power centralization and Personality Cults

Xi Jinping, a once unassuming bureaucrat, became China’s leader following his election as General Secretary of the Communist Party of China and Chairman of the Central Military commission in 2012. Starting his tenure with grandiose promises to address party corruption and make China a preeminent world power, one of his first moves as China’s leader was launching the largest anti-corruption purge in the history of the nation. With rampant internal corruption a systemic and entrenched issue within the party, few could fault the move. However, many have pointed to the targets of the drive, potential rivals and supporters of opposition as evidence that the purge was little more than a consolidation of power. Bo Xilai, the former mayor of Chongqing and rising party member, serves as a stellar example. Once seen as Xi Jinping’s competitor he is now facing life in prison for corruption and power abuse, charges which many point to as politically motivated and only beneficial to Jingping.

While breaking precedent to persecute high level national officials is undoubtedly positive and carries with it a great potential to usher in more accountability from government officials, such purges have proved typical of leaders who aspire to transition into dictators. While the methodology was much more benign then Hitler’s Night of the Long Knives where supreme control over the NSDAP was established through blatant murder, one cannot help noticing how the end result; consolidated internal control is the same.

The most illuminating action thus far in Xi’s possible dictatorial ambitions has been the removal of the two term limit introduced by Deng Xiaoping on the Chinese presidency. Deng supposedly introduced the term limit in order to prevent any leader from gaining too much power and repeating the bloody purges of the Mao era. Chinese state media has claimed that Xi’s removal of the term limit makes sense as the other two posts he holds in China’s “trinity of leadership” system: party secretary and military commission chairman positions which do not have any term limits. However many have pointed to the move as one which cements his ability to hold future power by preventing any potential rivals from coming forth. Combined with the anti-corruption purge such power centralization does not bode well for aspiring democrats in the nation.

Under Xi Jinping, the state propaganda machine has been working on overdrive in an attempt to generate a populist appeal between him and the people. Pictures have been taken showing Xi with farmers and other working people, whilst state media showers titles on him such as “the unrivalled helmsman” and “man who makes thing happen”. Many have stated that Xi’s growing personality cult is reminiscent of that under Mao. Indeed, “Xi Jingping Thought”, his official leadership and guidance doctrine has been added as an official preamble to the constitution, the first time this has been done for a ruling leader since Mao.

Indoctrination, Ideology and Erasure

The increase in these cultish ‘cult of personality’ characteristics has coincided with an increase in state censorship. Following Xi’s removal of term limits, the government censored numerous phrases online including 1984, animal farm, and personality cult. Following a state visit by Obama a meme comparing Xi walking next to Obama was erased from across the Chinese internet. Such internet censorship does not just include the deletion of social media posts and other “subversive” content, but the active creation of posts. A 2016 Harvard study estimated that the Chinese government was responsible for the fabrication of 448 million social media comments on Chinese social media platforms such as Weibo. Such a massive output combined with such expansive censorship is carried out by an extensive censorship army employed by the government, which was estimated to number 2 million people in 2013.

While the levels of censorship is worrying, what is perhaps even more distressing – and undoubtedly totalitarian – is the government’s active erasure and censorship of history. As the Soviet Union did until Gorbachev’s thaw, officials tightly control what can and cannot be said about the countries past. The aforementioned media censors trawl the internet erasing any mentions of the Tiananmen square massacre, while Xi Jingping attempts to remould the Chinese education system to produce good communist youths. Xi Jinping’s new curriculum includes greater emphasis on China’s communist party heroes as well as China’s ancient confucian past. In such a learning environment any mention of the extensive cultural destruction that took place and large scale massacres would doubtless be taboo.These aspects of censorship have even found themselves making their way abroad with prominent scholars discussing controversial or “subversive” topics such as Tibet or the Tiananmen square massacres, finding themselves denied visas of entry to the country which they have dedicated their life to studying.

China’s minority Uighur population has borne the brunt of Xi’s new ideological education drive. As a minority Muslim population, the Uighurs have faced numerous abuses and persecution from the Chinese government. The Chinese government’s ideologically driven onslaught against the Ughurs has included measures such as the wholesale destruction of mosques, banning of beards and headscarves, and most chillingly, the mass internment and detention of ethnic Uighurs without charges. China’s government has placed an estimated 1 million Uyghur muslims into camps which they allege are vocational skill education centers. Former dissidents however have told tales of torture and forced learning of Chinese propaganda. Such measures are the closest China has come to re-living the horrors of the cultural revolution which saw the nation-wide destruction of religion and mass detainment in labor camps alongside intense marxist-leninist ideological indoctrination.

Utopia

While the aforementioned are far from ideal, they represent fairly standard authoritarian practice with similar such policies adopted in a wide range of non-democratic countries throughout the world. Where China’s real totalitarian ingenuity stands out is in the creation of a new social credit score system. The idea is very simple, assign every citizen a base score which will decrease when bad behaviour such as jaywalking is observed and increase with good behaviour such as giving to charity, in essence regulating the nuanced behaviour of everyday life. The punishments for anti-social behaviour include being blocked from travel, certain jobs and having your children unable to attend the best schools.

Despite the fact that such punishments may seem benign, the implications of the creation of such a system are huge. Such a system opens up a massive sphere for potential use and abuse of the system by both citizens and the state. If citizens have the freedom to potentially report on bad social behaviour such a power may be used, as it has in several previous totalitarian regimes. Those who have studied the Gestapo and Stasi noted that it was not the extensive state apparatus which was responsible for finding people but rather everyday informants who turned people in. While at present such a risk may seem small with one of the violations including “ breaking party rules”, where the potential for abuse is rife particularly if the system were to become more expansive. The Chinese government insists the move will generate greater trust and harmony in society, however under a system where the slightest infraction can have lasting real-world effects, as ended up happening in other states which sought to usher in societal utopia, the opposite will happen.

Closing Thoughts

According to Hannah Ardent the critically acclaimed author of “the Origins of Totalitarianism”, who studied the Nazi and Soviet totalitarian regimes totalitarianism thrived and was marked by a contempt for the truth. With a state that is yet to live up to the crimes of its past and trims the press and internet of dissent, it would appear that China has already reached this place. One can only hope that the citizens that constitute it continue to resist (as many have) and question the system which permeates their everyday life before it extends too far.