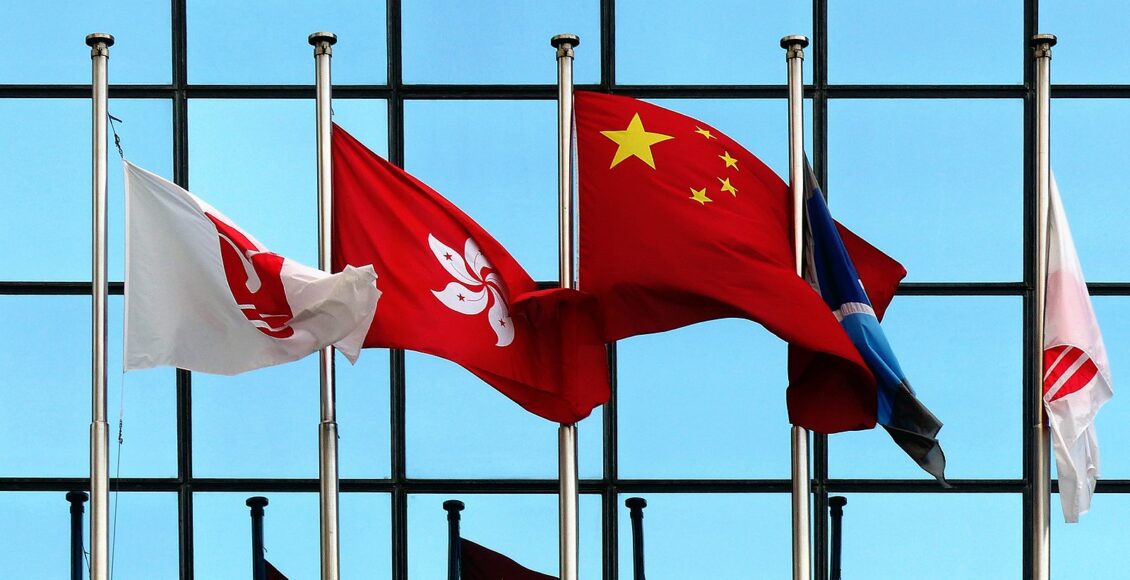

China’s push for Uniformity: the Future of Cantonese in Hong Kong

Hong Kong

In 1842, when the Qing Dynasty in China ceded Hong Kong Island to the British after the First Opium War, it set in motion a process that would affect the history of the region. It is a history that was destined to be both politically and socially distinct from its mainland counterpart. In 1898, China officially leased the Island of Hong Kong (in addition to a few other islands and the mainland region of Kowloon) to Britain for 99 years. Over the course of a century and a half, it developed into an economic powerhouse with booming film and business industries. Although never deemed a full democracy, Hong Kongers enjoyed democratic institutions and freedom of movement and speech, rights their mainland counterparts were denied.

The Handover in 1997 represented the official end of all official British rule in the region; for 50 years following the Handover, the region was set to be ruled under the concept of “one country, two systems.” Pioneered by Deng Xiaoping, this concept was popularized in the 1980s as China began to slowly open up to the world. In theory, it meant the people of Hong Kong could enjoy similar freedoms they had come to expect after over a century and a half of British rule as they transitioned from a British colony to a Special Administrative Region under China (similar to Macau). The people of Hong Kong were guaranteed the right to possess numerous political parties, the right to freedom of speech and assembly, and the right to an independent judiciary branch. These rights are codified in the Basic Law, a document which many consider to be the closest thing Hong Kong has to a constitution.

China’s economic position impacted their ‘hands-off’ decision-making during the first few years following the Handover. Hong Kong still held a position of economic superiority over most Chinese cities; British rule was also incredibly fresh in the minds of Hong Kongers. Nonetheless, it didn’t take long for the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) to exercise its reach. In 2003, Article 23 was introduced by Tung Chee-hwa’s administration, followed by a march of over 500,000 people in protest. The article proposed to restrict acts determined as “treasonous.” Although the article was suspended indefinitely, the following decades witnessed an increasing encroachment of the CCP into Hong Kong’s political sphere.

From commemorating the Tiananmen Square Massacre to the right to elect legislators without approval from Beijing- the people of Hong Kong took to the streets to protest. Most famously, during the Umbrella Movement of 2014, over 1 million people protested the implementation of the National Security Law, which curtailed freedom of speech, movement, and protection from unlawful search and seizure.

What is Cantonese?

Over 85.5 million people speak Cantonese worldwide, although some estimate the number to be significantly higher. Originating in the Guangdong region, it is the primary language of Hong Kong, with 88.2 percent of residents speaking the language at home. The fuel behind the booming cinema industry of the 1960s and 70s, Cantonese is a key point of identification for many who call themselves Hong Kongers.

But what exactly is Cantonese? The CCP labels it a dialect, one of many to be found within the region and one of many that is to be purged in pursuit of a universal Mandarin to be spoken across China. Mandarin, also known as Putonghua, is a dialect from Beijing and is said to be spoken by 2/3rds of China’s population. Numerous regional dialects, such as Shanghainese and Fuzhonese, are being phased out by the CCP in pursuit of a universal Putonghua. Cantonese, in contrast, is not mutually intelligible with Mandarin– meaning speakers of Cantonese cannot understand Putonghua, and vice versa. By marking Cantonese as simply a dialect of Putonghua, the CCP eliminates a crucial aspect of the Hong Kong identity.

The CCP’s Push for Uniformity

Language in most of the world is politicized, whether it be to advocate distinctness or pursue uniformity. The CCP is no different; it has stated that by 2025, 85 percent of Chinese citizens will use Mandarin, and the language will be universal within China by 2035. Xi Jinping has stressed the importance of promoting Mandarin in ethnic minority regions from the earliest point of education to ensure their success. Most recently, in 2021, the CCP ended all Mongolian-language education in Inner Mongolia.

This push for uniformity comes at a time of significant political meaning. The CCP celebrated their 100-year anniversary in July of 2021, and Xi Jinping’s vision for China’s next 100 years is one of uniformity that “break[s] lineage, break[s] roots, break[s] connections and break[s] origins.” The pursuit of total control of its semi-autonomous zones (regions within the country that enjoyed a small level of independent governance) grew exponentially after the 2008 Tibet riots and the arrival of Xi Jinping as leader in 2012.

Language is but one avenue through which the CCP is pursuing uniformity within its borders; Han Chinese citizens are incentivized to settle in provinces populated by ethnic minorities, intermarriage is encouraged, and ethnic minorities are encouraged to leave their home provinces to work elsewhere. The CCP’s systematic persecution of Uyghurs in Xinjiang province is one of the most prominent examples, but parallels in policy can be witnessed across the region. James Leibold, an expert at La Trobe University in Australia commented on these measures, stating “Xinjiang might be the sharp end of the arrow, but there’s a very long shaft that stretches right across China.”

For Hong Kongers, the CCP’s attempt to phase out Cantonese from Hong Kong life indicates an attempt to eradicate their unique identity. Cantonese slang and satire played a major role in the 2019 protests against extradition to mainland China, and many other demonstrations beforehand. Robert Bauer, a researcher on Cantonese and a teacher at numerous universities in Hong Kong, states that “[s]peaking, and writing, Cantonese has now become a political act.” Indeed, many who oppose the reach of the CCP view the speaking of Putonghua as taboo and refuse to use it, even if they are able to.

This composite character combines 和(peace) & 勇(brave) as a call for unity between the two camps of Hong Kong's protest movement: the 勇武 "brave fighters" up on the frontlines, & the 和理非 “peaceful, rational, non-violent” camp, who want to keep confrontations to a minimum pic.twitter.com/H2lJj5X6Cr

— Mary Hui (@maryhui) August 21, 2019

What is the future of Cantonese in Hong Kong?

Within Hong Kong, the slow shift away from Cantonese as the language of everyday life and business has grown in the last few years. Although English has always had a prominent place in Hong Kong’s education and business, the community continues to hold Cantonese as their lingua franca. Nonetheless, the number of Hong Kongers able to speak Mandarin has greatly increased, rising from 25% in 1996 to 54.2% in 2021, following the CCP’s concerted efforts to promote Mandarin in schools and business.

As of 2019, 70 percent of Hong Kong’s elementary schools teach primarily in Mandarin, and much of the nightly news is read in the language. Altogether, while the number of Cantonese speakers has not witnessed an enormous drop-off, the growth of Mandarin points to an increased political presence of Mainland China, and therefore the CCP, within Hong Kong. Over 144,000 Hong Kongers, feeling this pressure, have left under the British National Overseas scheme since 2020.

In 2020, “Our Time” was published, a dystopian short story written anonymously in Cantonese and shortlisted by Gongjyuhok (a writing competition sponsored by the Hong Kong government). It tells the story of a young man visiting Hong Kong in 2050 from the UK, where he grew up after his parents emigrated in 2020. The Hong Kong he visits is completely different from the stories his parents told him as a child. The story ends with the sentence, “[t]he struggle between man and totalitarianism is the struggle between memory and forgetting.” The home of the writing competition’s founder was searched without a warrant in 2023, with authorities claiming the story’s publication violated the National Security Law.

The community of Hong Kong faces increased pressure to conform to the CCP’s idea of what it means to be Chinese –whether that be through language, freedom, or education. As politics influence the use of language and vice versa, one wonders: how many Hong Kongers will speak Cantonese two hundred years from now?

Edited by Sarenna McKellar.