China’s Quiet Experiment with Democracy

Photo by Jennifer Chen on Unsplash

Photo by Jennifer Chen on Unsplash

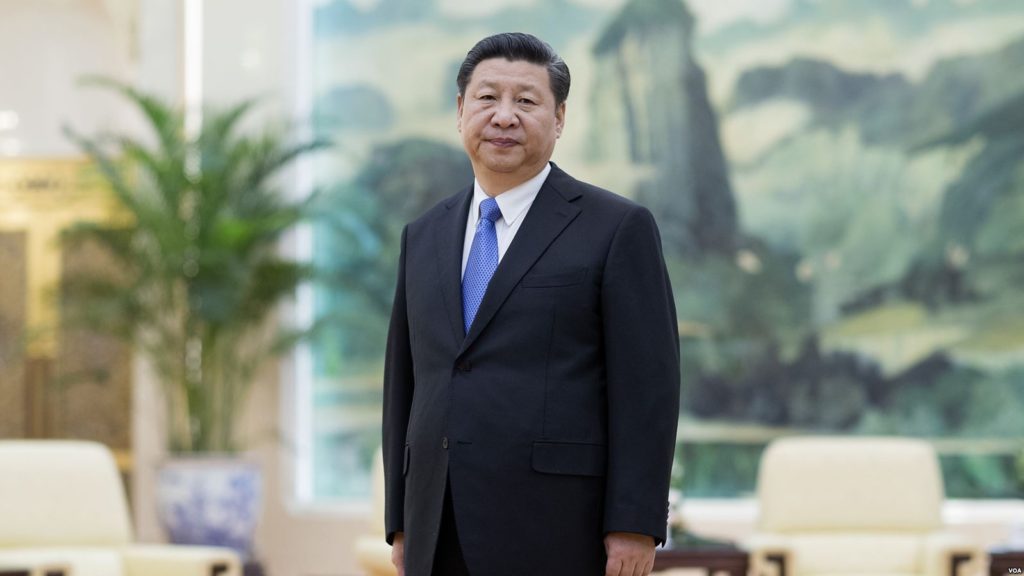

The People’s Republic of China, established in 1949 under the one-party rule of the Chinese Communist Party, is an authoritarian regime by all standards. There are no free elections at the national level, media freedom is severely restricted, and any dissent against the government is quickly suppressed. In its Freedom in the World 2018 index, Freedom House gave China a meagre aggregate score of 14/100, with zero being the least free and 100 being the most; one of the lowest scores in Asia. This was in part due to the abolishment of term limits in May, which allows Xi Jinping, the incumbent Premier of China, to theoretically continue his rule indefinitely.

Despite the current situation, elements of democracy have been slowly introduced into Chinese society over the past 20 years, such as the establishment of relatively free elections at the village level for a village committee and chief, as well as an increase in the number of successful lawsuits against the government by both non-government organizations (NGOs) and individuals. Does this point towards a desire from the government to eventually bring China on the path towards democracy? Or is it just an attempt to appease the population without any meaningful, long lasting change?

Perhaps the most visible of the attempts at establishing aspects of democracy is beginning the village elections, where residents are able to directly elect their leaders. In 1988, the Organic Law of Village Committees was passed by the national government, establishing regulated elections throughout the country. Under this law, elections would occur every three years, and any voter can nominate a candidate. At first, these elections ran into many problems such as vote-buying, harassment, and the presence of organized crime, which are typical for fledgling democratic systems. Although many issues still persist, villages across the country have adapted and brought changes to their electoral systems in order to make elections fairer. Some features that have since become standard include the implementation of the secret ballot, restrictions on proxy voting (in which one elector votes on behalf of others in their absence), and public counting of ballots. Turnout among villagers have continued to be high, reaching over 90% in some areas, and the legitimacy of these elections have been confirmed by various international monitors.

However, the elections are still far from perfect, as tensions have arisen between the elected village leadership, the unelected township government, and the local Communist party branch. The latter institutions see themselves as superior to the former, and frequently interfere or overrule the decisions made by the elected representatives. For the most part, villagers support elected officials, as they are accountable to the electorate. Meanwhile, businesses and other outside interests back the township government, as they often benefit from contracts or other benefits. This tension is most clearly exemplified in the Wukan protests. In 2011, villagers from Wukan, a small village in the southern Chinese province of Guangdong, protested against government officials for the sale of farmland without their consent to real estate developers; one of the latest in a series of corruption allegations. In response, the government was originally willing to negotiate with 13 democratically elected representatives over the conflict, but later reneged and arrested five representatives. This resulted in further protests, as well as the local government and police being ousted from the village. A siege by the police ensued, only coming to an end when provincial officials stepped in and negotiated a settlement. After the incident, the land sale was halted, and detained representatives were released. Interestingly, the government allowed free elections to continue in 2012, and one of the former leaders of the protest was even elected the village chief. The fact that the government did not attempt to end elections suggests that it considers them valid.

Alongside the implementation of village elections, the national government also introduced an amendment to the Civil Procedure Law and the Environmental Protection Law, which allowed NGOs that have not violated any law in the past five years to initiate public interest lawsuits. This was followed up with another amendment in 2017, which allowed prosecutors to initiate public interest lawsuits in additional areas, such as in matters dealing with food and drug safety, preservation of state assets, and transfer of state-owned land use rights. As a result, the amendments have led to a large increase in lawsuits against government agencies as well as individual officials, with an increasing number of rulings in favour of the plaintiff. Similarly, NGOs have been equally successful in winning environmental lawsuits against companies accused of excess pollution. This is a stark contrast from China’s policy just a decade ago, when such cases would almost always result in a favourable ruling for the defendant. More often, the complaint would simply be ignored by the courts. These new amendments, combined with the village elections, point to a shift in strategy when dealing with conflict. Instead of simply dismissing all complaints made by the people, the government is opting to allow citizens to voice to their grievances and resolving them if is deemed necessary.

Despite these reforms, it is clear that the one-party state is still very much in control of political power, and is unwilling to relinquish it anytime soon. However, its efforts at introducing low level elections to the masses (600 million people, or almost 45% of the population, live in villages) and consolidating rule of law hint towards an effort to familiarize citizens to aspects of democracy. If so, what is the motivation for this seemingly contradictory behaviour?

One possible explanation is that in the long term, the Chinese government hopes to implement democracy on a much wider scale. By allowing small scale elections now, the government is able to refine the system over time, so that when free elections might be implemented on a province-wide or nation-wide scale, people are already familiar with the systems and are able to make a more informed vote. This would allow for a smooth transition process and prevent the breakdown of democracy. Furthermore, the gradual reform on tort law increases demand for lawyers and other legal professionals, allowing for more qualified candidates to become judges and politicians, increasing the quality of their work. In the meantime, they are at least able to work in order to prevent companies and government agencies from operating above the law, protecting citizens and promoting their interests throughout the country.

However, a counterargument can be made that these reforms are only a way to appease the population. After more than 20 years of village elections, no further effort has been made to allow free elections on any other level, and crackdowns on advocates for democracy are just as common as before. If that was the case, then why has the Communist party simply shut down the elections? By doing so, they would be able to save a significant amount of time and money, as they would not need to spend more cash on elections, and they can have township governments make decisions without further hinderance. By not passing reforms on litigation, the state can continue with massive development projects to stimulate the economy and efficiency, without anyone standing in the way.

Given all this information, it is important to note that Chinese society has become reluctant to pursue a radical change in government (as previous attempts in the 19th and 20th century such as the Taiping rebellion, Boxer rebellion, and the Chinese civil war prove) all resulted in the deaths of millions of Chinese people without delivering the massive changes that were promised. Furthermore, for the past 30 years under the current Communist regime, China has experienced unprecedented economic growth, which has improved the quality of life for hundreds of millions, while establishing China as a superpower on the international stage. For the average citizen, stability and continued economic growth is a much higher priority than political reform, and as long as that trend continues, it is unlikely that the Communist party’s rule will be under threat.

China continues to be one of the least democratic countries in Asia, with the complete absence of citizen elections for almost all levels of government and little tolerance for any criticisms directed in its way. Despite that, it has also introduced some aspects of democracy by introducing free elections at the village level as well as increasingly liberalized reforms to private law. While it is clear that these reforms are minuscule in the grand scheme of things, the fact that such reforms are implemented at all and have remained in place indicates that the government must reap some economic or social benefit. Just what exactly those benefits are remains to be seen.

Edited by: Helena Martin